Decoupling or recoupling?

An old Chinese myth

Contrary to popular wisdom, China's rapid growth is not hugely dependent on exports

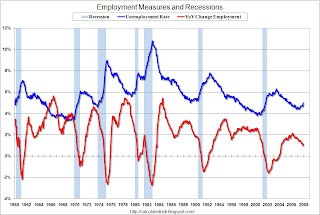

MOST people suppose that China's economic success depends on exporting cheap goods to the rich world. If so, its growth would be seriously dented by a stuttering American economy. Headline figures show that China's exports surged from 20% of GDP in 2001 to almost 40% in 2007, which seems to suggest not only that exports are the main driver of growth, but also that China's economy would be hit much harder by an American downturn than it was during the previous recession in 2001. If exports are measured correctly, however, they account for a surprisingly modest share of China's economic growth.

The headline ratio of exports to GDP is very misleading. It compares apples and oranges: exports are measured as gross revenue while GDP is measured in value-added terms. Jonathan Anderson, an economist at UBS, a bank, has tried to estimate exports in value-added terms by stripping out imported components, and then converting the remaining domestic content into value-added terms by subtracting inputs purchased from other domestic sectors. At first glance, that second step seems odd: surely the materials which exporters buy from the rest of the economy should be included in any assessment of the importance of exports? But if purchases of domestic inputs were left in for exporters, the same thing would need to be done for all other sectors. That would make the denominator for the export ratio much bigger than GDP.

Once these adjustments are made, Mr Anderson reckons that the "true" export share is just under 10% of GDP. That makes China slightly more exposed to exports than Japan, but nowhere near as export-led as Taiwan or Singapore (which on January 2nd reported an unexpected contraction in GDP in the fourth quarter of 2007, thanks in part to weakness in export markets). Indeed, China's economic performance during the global IT slump in 2001 showed that a collapse in exports is not the end of the world. The annual rate of growth in its exports fell by a massive 35 percentage points from peak to trough during 2000-01, yet China's overall GDP growth slowed by less than one percentage point. Employment figures also confirm that exports' share of the economy is relatively small. Surveys suggest that one-third of manufacturing workers are in export-oriented sectors, which is equivalent to only 6% of the total workforce.

Even if the true export share of GDP is smaller than generally believed, surely the dramatic increase in China's exports implies that they are contributing a rising share of GDP growth? Mr Anderson's work again counsels caution. Although the headline exports-to-GDP ratio has almost doubled since 2000, the value-added share of exports in GDP has been surprisingly stable over the same period (see left-hand chart). This is explained by China's shift from exports with a high domestic content, such as toys, to new export sectors that use more imported components. Electronic products accounted for 42% of total manufactured exports in 2006, for example, up from 18% in 1995. But the domestic content of electronics is only a third to a half that of traditional light-manufacturing sectors. So in value-added terms exports have risen by far less than gross export revenues have.

Many of China's foreign critics remain sceptical. They argue that China's massive current-account surplus (estimated at 11% of GDP in 2007) proves that it produces far more than it consumes and relies on foreign demand to buy the excess. In the six years to 2004, net exports (ie, exports minus imports) accounted for only 5% of China's GDP growth; 95% came from domestic demand. But since 2005, net exports have contributed more than 20% of growth (see right-hand chart).

This is due not to faster export growth, however, but to a sharp slowdown in imports. And even if the contribution from net exports fell to zero, China's GDP growth would still be close to 9% thanks to strong domestic demand. The boost from net exports is in any case unlikely to vanish, even if America does sink into recession, because exports to other emerging economies, where demand is more robust, are bigger than those to America. According to Standard Chartered Bank, Asia and the Middle East accounted for more than 40% of China's export growth in the first ten months of 2007, North America for less than 10%.

Multiplier effects

China's economy is driven not by exports but by investment, which accounts for over 40% of GDP. This raises an additional concern: that weaker exports could lead to a sharp drop in investment because exporters would need to add less capacity. But Arthur Kroeber at Dragonomics, a Beijing-based research firm, argues that investment is not as closely tied to exports as is often assumed: over half of all investment is in infrastructure and property. Mr Kroeber estimates that only 7% of total investment is directly linked to export production. Adding in the capital spending of local firms that produce inputs sold to exporters, he reckons that a still-modest 14% of investment is dependent on exports. Total investment is unlikely to collapse while investment in infrastructure and residential construction remains firm.

An American downturn will cause China's economy to slow. But the likely impact is hugely exaggerated by the headline figures of exports as a share of GDP. Dragonomics forecasts that in 2008 the contribution of net exports to China's growth will shrink by half. If the impact on investment is also included, GDP growth will slow to about 10% from 11.5% in 2007. This is hardly catastrophic. Indeed, given Beijing's worries about the economy overheating, it would be welcome.

The American government frequently accuses China of relying excessively on exports. But David Carbon, an economist at DBS, a Singaporean bank, suggests that America is starting to look like the pot that called the kettle black. In the year to September, net exports accounted for more than 30% of America's total GDP growth in 2007. Another popular belief looks ripe for reappraisal: it seems that domestic demand is a bigger driver of China's growth than it is of America's.

Mutual Fund Oscars

Morningstar Singles Out

Fidelity's Danoff on Stocks,

Pimco's Gross on BondsTwo well-known mutual-fund managers who steered clear of the subprime-loan downturn in 2007 and delivered impressive returns to stock and bond investors received honors yesterday from investment researcher Morningstar Inc.

Will Danoff, of Fidelity Contrafund, one of the country's biggest mutual funds, and the smaller Fidelity Advisor New Insights Fund, was named Morningstar Domestic Stock Fund Manager of the Year.

![[Will Danoff]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-CP664_Danoff_20051031180419.gif)

Meanwhile, Morningstar's Fixed-Income Manager of the Year went to Pacific Investment Management Co.'s Bill Gross. His team running Pimco Total Return and Harbor Bond Fund has won the award three times. Pimco is a unit of Allianz SE.

Separately, Hakan Castegren, lead manager at Harbor International Fund, was selected International Stock Manager of the Year, an award he won also in 1996. The foreign large-cap value fund returned 21.8% in 2007, topping 96% of its class, Morningstar said.

Mr. Danoff led the $80.8 billion Contrafund to a 19.8% gain in 2007, topping its large-cap growth category average by more than six percentage points, according to Morningstar.

Technology stocks worked especially well in 2007 for the fund, which is closed to new investors. Mr. Danoff pointed to top performers including Research In Motion Ltd, Google Inc. and Apple Inc.

"Avoiding financials was a big win, as well," Mr. Danoff said. "When I saw many of the issues financials were wading through, I stepped back."

If markets decline in 2008, he adds, Contrafund's team will likely use it as an opportunity for long-term-minded shareholders to buy into companies with strong fundamentals and top management.

![[William Gross]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-GK507_Gross_20070823220030.gif)

Mr. Danoff says another key performer in 2007 was the fund's investment in energy and materials sectors. "Those turned out to be very good this year, and that really helped the fund's returns," he added. "And with decent demand coming out of emerging markets, prices continue to be strong."

Morningstar gives awards to managers each January based on strong investment performance in the previous calendar year, superior long-term results, and a proven commitment to investors in their funds.

"All of this year's winners made real money for investors this year as well as over longer periods," said Christine Benz, director of mutual-fund analysis at Morningstar. "These are all very consistent performers."

She noted that Mr. Danoff's Contrafund dropped 10% in 2002 versus the broader market's 22.1% loss. During the past 10 years, the fund's average annualized return of 10.7% tops 96% of its large-cap growth rivals, Ms. Benz added.

"It was a $30 billion in assets-under-management fund," Ms. Benz said. "Danoff's record has built quite a following over the years."

Morningstar emphasized that its international award in 2007 went to the team Castegren leads, which includes analysts at asset manager from Boston-based Northern Cross International Investment Management.

"The team has shown a lot of patience in looking for bargain stocks," Ms. Benz said. "He's very long-term focused and has been on the fund for 20 years. This is another large fund, with $27.2 billion in assets and very stable management."

Meanwhile, Mr. Gross is one of the most-respected bond-fund managers in the business, she added. "He's our only three-time winner," Ms. Benz said. "He's a manager who isn't afraid to take bold stances when he and his team thinks it will profit investors over the long term."

For example, in 2006, long before anyone else was worried about a downturn in housing, Mr. Gross moved to shield his portfolios from a downturn, Ms. Benz said. "At first, that led the fund to look out of step with its intermediate bond-fund peers," she added.

Still, Pimco Total Return was able to put up results close to the category's average. "But that was relatively weak for such a strong long-term performer," Ms. Benz said. "It's not typically an average, run-of-the-mill type of bond fund."

In 2007, bets by Mr. Gross and his team paid off. In the year, it posted a preliminary 9.1% total return versus 4.7% for its peer group.

In addition to this year's bond-fund manager of year award, Mr. Gross won for the same category in 1998 and 2000.

"It has been an honor and a real team effort in each of those years, especially in 2007," Mr. Gross said. "Our success came from avoiding the subprime debacle and taking advantage of the policy moves, namely the Fed cuts, that emanated from it."

China’s SWF Act Again

China Taps Its Cash Hoard To Beef Up Another Bank

Source: WSJAn injection of $20 billion by China's sovereign-wealth fund into policy lender China Development Bank is the latest example of how the country is using its surplus of cash to beef up the balance sheets of local banks.

The newly formed fund, China Investment Corp., or CIC, has attracted much attention overseas for its high-profile purchase of stakes in U.S. private-equity firm Blackstone Group LP and, two weeks ago, Wall Street firm Morgan Stanley. But the fund, formed from $200 billion of foreign-exchange reserves, has set aside as much money for recapitalizing domestic financial institutions as for overseas investment.

China Development Bank, known as CDB, has also cut a global profile recently. Earlier in 2007, it invested $3 billion in Barclays PLC to help support the British bank's ultimately unsuccessful bid for ABN Amro Holding NV. It has specialized in lending to domestic infrastructure projects and has been a pioneer in developing China's nascent bond markets.

![[Balancing Act chart]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AI-AM550_CDB_20080101161246.gif)

Plans for the capital injection into CDB had been in the works since at least last January. Beijing had already dipped into its bulging foreign-exchange reserves, now topping $1.4 trillion, to shore up the books of the country's three biggest listed banks ahead of their initial public offerings. Capital injections into those banks from Central Huijin Investment Co., a government agency that has been incorporated into CIC, totaled about $60 billion.

Now those formerly insolvent state-owned lenders, led by Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd., rank among the world's biggest banks. They have begun to use the massive sums raised by their initial public offerings to expand globally.

Next in line for a huge pre-IPO infusion will be Agricultural Bank of China. CIC is expected to inject about $45 billion to rehabilitate the sprawling state bank and prepare it for an IPO.

China's central bank announced the CDB capital injection in a statement posted Monday on its Web site, saying the infusion will "increase China Development Bank's capital-adequacy ratio, strengthen its ability to prevent risk, and help its bank move toward completely commercialized operations." The move appears timed to ensure CDB can count the fresh capital on its 2007 books.

Formed in 1994, CDB is in some ways a World Bank with Chinese characteristics. It has been molded by the leadership of Chen Yuan, a former central-bank vice governor and son of Chen Yun, who was one of the architects of China's economic overhauls. He has looked to outsiders like former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker for advice and asked international auditors to check his bank's books. At the same time he used his bank's money to back major government initiatives like the Three Gorges Dam — a project the World Bank decided against funding. The bank has been active in lending to Chinese projects abroad, including through a fund it set up to focus on Africa, and in supporting Chinese companies looking to expand overseas.

CDB's capital base has been pinched by continued lending growth without an increase in equity. It doesn't get its funding from deposits by China's 1.3 billion people, instead relying for most of its capital on bond sales — which have totaled more than two trillion yuan ($274 billion) since its founding.

The bonds represent about one-fifth of the debt securities outstanding on China's financial markets. Internationally, CDB has issued more bonds than any other Chinese institution.

At the end of 2006, the bank said its capital-adequacy ratio slipped by one percentage point to just above 8%, the lowest level Chinese regulators consider safe.

As most of CDB's lending is to government agencies, or projects backed by Beijing, loan losses have tended to be low. Of the 576 billion yuan in loans it disbursed in 2006, nearly 20% went to each of three sectors: power, road and public facilities.

A CDB spokeswoman said the bank had no comment on the injection beyond the central bank's statement.