Home » nobel

Category Archives: nobel

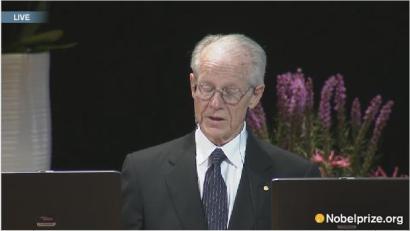

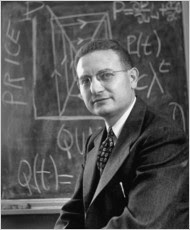

Paul Samuelson dies at 94

Paul Samuelson, the great American economist, one of the true masters in the history of economics in the 20th century, along with J. M. Keynes, F. Hayek, Milton Friedman, dies at 94 yesterday (Dec. 13th) at his Belmont MA home. Here is eulogy piece from NYT:

His death was announced by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which Mr. Samuelson helped build into one of the world’s great centers of graduate education in economics.

In receiving the Nobel Prize in 1970, Mr. Samuelson was credited with transforming his discipline from one that ruminates about economic issues to one that solves problems, answering questions about cause and effect with mathematical rigor and clarity.

When economists “sit down with a piece of paper to calculate or analyze something, you would have to say that no one was more important in providing the tools they use and the ideas that they employ than Paul Samuelson,” said Robert M. Solow, a fellow Nobel laureate and colleague of Mr. Samuelson’s at M.I.T.

…

Mr. Samuelson wrote one of the most widely used college textbooks in the history of American education. The book, “Economics,” first published in 1948, was the nation’s best-selling textbook for nearly 30 years. Translated into 20 languages, it was selling 50,000 copies a year a half century after it first appeared.

…

A historian could well tell the story of 20th-century public debate over economic policy in America through the jousting between Mr. Samuelson and Milton Friedman, who won the Nobel in 1976. Mr. Samuelson said the two had almost always disagreed with each other but had remained friends. They met in 1933 at the University of Chicago, when Mr. Samuelson was an undergraduate and Mr. Friedman a graduate student.

Unlike the liberal Mr. Samuelson, the conservative Mr. Friedman opposed active government participation in most areas of the economy except national defense and law enforcement. He thought private enterprise and competition could do better and that government controls posed risks to individual freedoms.

Both men were fluid speakers as well as writers, and they debated often in public forums, in testimony before Congressional committees, in op-ed articles and in columns each of them wrote for Newsweek magazine. But Mr. Samuelson said he always had fear in his heart when he prepared for combat with Mr. Friedman, a formidably engaging debater.

“If you looked at a transcript afterward, it might seem clear that you had won the debate on points,” he said. “But somehow, with members of the audience, you always seemed to come off as elite, and Milton seemed to have won the day.”

Mr. Samuelson said he had never regarded Keynesianism as a religion, and he criticized some of his liberal colleagues for seeming to do so, earning himself, late in life, the label “l’enfant terrible emeritus.” The experience of nations in the second half of the century, he said, had diminished his optimism about the ability of government to perform miracles.

If government gets too big, and too great a portion of the nation’s income passes through it, he said, government becomes inefficient and unresponsive to the human needs “we do-gooders extol,” and thus risks infringing on freedoms.

But, he said, no serious political or economic thinker would reject the fundamental Keynesian idea that a benevolent democratic government must do what it can to avert economic trouble in areas the free markets cannot. Neither government alone nor the markets alone, he said, could serve the public welfare without help from the other.

As nations became locked in global competition, and as the computerization of the workplace created daunting employment problems, he agreed with the economic conservatives in advocating that American corporations must stay lean and efficient and follow the general dictates of the free market.

But he warned that the harshness of the marketplace had to be tempered and that corporate downsizing and the reduction of government programs “must be done with a heart.”

Despite his celebrated accomplishments, Mr. Samuelson preached and practiced humility. The M.I.T. economics department became famous for collegiality, in no small part because no one else could play prima donna if Mr. Samuelson refused the role, and, of course, he did. Economists, he told his students, as Churchill said of political colleagues, “have much to be humble about.”

Something about Joe Stiglitz

A brief yet very interesting piece on economist Joe Stigliz (source: IMF). Here are some excerpts:

…

…

In 1993, Stiglitz abandoned his comfortable perch in academia for the rough-and-tumble of the policy world. He became a member of Clinton’s CEA and later its chairman. Alan Blinder, a Princeton professor and a fellow CEA member, describes it as “a gutsy move for a purely academic superstar.” Stiglitz was instrumental in pushing through several initiatives, including persuading a somewhat reluctant U.S. Treasury to issue inflation-indexed government debt. But Chait wrote in The American Prospect that Stiglitz’s style of argument—making his case publicly even after losing internal debates on issues—led to wintry relationships with other presidential advisors, such as Larry Summers. Blinder says politely that “Joe’s behavior . . . might perhaps be considered a little quixotic.”

This style grew even more pronounced after Stiglitz moved in 1997 from the White House to become World Bank chief economist. He was critical of the economic advice to the transition economies to carry out a speedy move to markets and capitalism. Stiglitz favored a much more gradual move, with legal and institutional reforms needed to support a market economy preceding the transition to markets. Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard professor and former chief economist of the IMF, doubts that Stiglitz’s approach would have succeeded. He says it is “unlikely that market institutions could have been developed in a laboratory setting and without actually starting the messy transition to the market.” Rogoff adds that because the institutions underpinning communism had collapsed, “some new institutions had to be created quickly,” and it is inevitable that mistakes were made in this haste. But “institutions take a long time to nurture and the ones that are there today, however imperfect, might well not be there if the effort had not been started” immediately when communism fell.

During the financial crisis of 1997–98, Stiglitz publicly criticized the programs put together by the IMF and the governments of some Asian countries. Stiglitz argued that raising interest rates to defend the currencies in these countries was counterproductive: the high interest rates reduced confidence in the economy by increasing loan defaults and corporate bankruptcies. Not everyone agreed with Stiglitz. The late MIT economist Rudiger Dornbusch defended the high-interest-rate strategy as essential to restoring confidence, adding that “no finance minister will opt for the Stiglitz Clinic of Alternative Medicine. They [will] have the ambulance rush them to the IMF.” J. Bradford DeLong, a noted macroeconomist at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote that following “Stiglitz’s prescriptions [to] lend more with fewer conditions and have the government print more money to keep interest rates low . . . would have been overwhelmingly likely . . . to end in hyperinflation or in a much larger-scale financial crisis as the falling value of the currency eliminated every firm’s and bank’s ability to repay its hard [foreign] currency debt.”

After exiting the World Bank in 1999, Stiglitz repaired to Columbia University and wrote what became a best-selling book titled Globalization and Its Discontents. Many reviewers of the book noted that its narrative power came from having a clear villain: the IMF. The book’s references to the IMF—almost all critical—totaled 340. Tom Dawson, the IMF’s external relations head at the time, quipped: “That works out to over one alleged mistake committed by the IMF per page. You’d think by sheer accident we’d have gotten a couple of things right.”

…

Despite the financial crisis, Stiglitz remains optimistic about the future of markets and capitalism. In contrast to “the 19th century owner-operated capitalism, in the 21st century capitalism will be operated by the people,” he says. But to make it a success, people have to be more economically literate and there has to be greater civic participation in economic policymaking. With these goals in mind, Stiglitz founded the Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD) in 2000—a global network of economists, political scientists, and policymakers that studies complex economic issues and provides policy alternatives to countries. IPD also conducts workshops to enable the media and civil society to participate effectively in policy circles. Dawson applauded the effort: “It’s a tough business—you almost have to be a Bono to have an impact on policy.”

Indeed, to reach wider audiences, Stiglitz has branched out into film with a documentary called Around the World with Joseph Stiglitz about how the fruits of capitalism can be shared more equally. Will it give filmmaker Michael Moore a run for his money? “No,” laughs Stiglitz, “I think Moore is very effective,” but “frustration doesn’t do any good.”

Unlike Moore, Stiglitz says he hasn’t lost his “Midwestern optimism” that things improve over the long run. Many people, he says, express their dismay to him that, with the financial crisis barely over, the bankers and their boosters seem to be back calling the shots. But if genuine reform of the financial system is not undertaken, “there is a reasonable risk of another crisis within 10–15 years, and the likelihood that the banks will win the next round is lower.” Every crisis provides “an impetus for deeper democratic reform. The game isn’t over.”

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=b69228cc-102f-4691-ac06-00b6a6bc7128)