Home » Uncategorized (Page 83)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

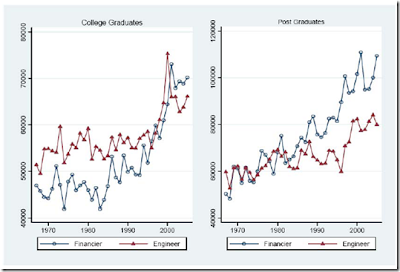

Financial Engineering vs. Real Engineering, Again

An update on my previous post on financial engineering vs. real engineering. Here is an interesting chart from MIT’s Andrew Lo. We are likely to see a sharp convergence of the two lines (esp. the post grads) in coming years.

Paulson: We stabilized financial system

Henry Paulson interview on CNBC:

Krugman says depression economics returns

Krugman writes on NY Times — His central message: this ain't normal time, so extraordinary measures are needed:

To see what I’m talking about, consider the implications of the latest piece of terrible economic news: Thursday’s report on new claims for unemployment insurance, which have now passed the half-million mark. Bad as this report was, viewed in isolation it might not seem catastrophic. After all, it was in the same ballpark as numbers reached during the 2001 recession and the 1990-1991 recession, both of which ended up being relatively mild by historical standards (although in each case it took a long time before the job market recovered).

But on both of these earlier occasions the standard policy response to a weak economy — a cut in the federal funds rate, the interest rate most directly affected by Fed policy — was still available. Today, it isn’t: the effective federal funds rate (as opposed to the official target, which for technical reasons has become meaningless) has averaged less than 0.3 percent in recent days. Basically, there’s nothing left to cut.

…

What does all this say about economic policy in the near future? The Obama administration will almost certainly take office in the face of an economy looking even worse than it does now. Indeed, Goldman Sachs predicts that the unemployment rate, currently at 6.5 percent, will reach 8.5 percent by the end of next year.

All indications are that the new administration will offer a major stimulus package. My own back-of-the-envelope calculations say that the package should be huge, on the order of $600 billion.

So the question becomes, will the Obama people dare to propose something on that scale?

Let’s hope that the answer to that question is yes, that the new administration will indeed be that daring. For we’re now in a situation where it would be very dangerous to give in to conventional notions of prudence.

Becker: No Silver Lining in Depression

Gary Becker argues against the idea that a severe recession or depression may help cleanse the excesses in the economy as the “Austrian” school of economics would claim. He explains why depression should be avoided at all cost.

Positive effects such as these may be somewhat important during very mild downturns, but they are overwhelmed during major recessions and depressions by the negative effects. I define a “major” recession as having an extended period of unemployment rates at 9 percent or more, coupled with declining GDP. It looks like the US and the world economies may be headed for such a recession for the next year or so.

Economists have underplayed the cost to individuals of mild to severe recessions in part because they have neglected the cost of the “fear” generated by bad economic times. In his1932 inaugural address in the midst of the Great Depression Franklin Delano Roosevelt reassured he American public that the “Only Thing We Have to Fear Is Fear Itself”. In fact they had a lot more to fear, but Roosevelt recognized the great importance of fear during depressions. In the present crisis too, consumers and workers have multiple fears due to various kinds of uncertainty. Homeowners fear that they may lose their homes after having used most of their savings as down payments on their homes. The employed fear that they will be laid off, while the unemployed fear that its duration will be quite long, and that they eventually will only get jobs that are much inferior to the ones they had. To be sure, some of the unemployed in many countries will receive unemployment compensation, but many unemployed American do not qualify for this benefit. Moreover, unemployed workers in this country usually receive much less than their earnings while employed, and after a while they run out of benefits, although benefits get extended during recessions.

The fear about losing one’s job interacts with fears about being unable to make payments on homes, cars, and other consumer durables. Unemployed persons start missing payments on their homes or cars. If this goes on for several months, they may have their cars repossessed, and their homes put into foreclosure, usually at a time when home prices are down a lot, so that can at best regain only a fraction of the equity they put into their homes.

In addition, the burden of a major recession is not shared uniformly. It usually falls disproportionately on unskilled workers, the young, and those in shaky financial positions, which tend to be persons with lower educations and incomes. For example, the unemployment rate of high school dropouts is traditionally several times that of college graduates, so when the average unemployment rate goes from 6 to 9 percent, that of college graduates may rise to about 4 percent, while that of dropouts will increase to over 20 percent. This recession may be a bit different since the financial sector is being hit so hard. Individuals and families already in shaky circumstances get hit especially hard by major recessions.

It is relatively easy to measure what happens to the unemployment rate during recessions and its differential incidence among different groups, or the number of persons who drop out of the labor force because they despair of finding a job. One can also measure relatively accurately the effects on profits, wages, the path of GDP and personal incomes, and other important variables. It is far harder to measure precisely the effects of serious recessions on individual welfare and happiness. Surveys of reported happiness find that workers who become unemployed are less happy than they were, and persons whose incomes have fallen reported a decline in their happiness, at least initially. Divorce rates and even suicide rates also tend to rise during major recessions, as does crime, discrimination against minorities and immigrants, and pressure toward greater protectionism.

Relative to these major costs, the alleged benefits of a recession to the United States seem quite small, and some of them could also be costs on balance. For example, how many infrastructure projects can be undertaken when states are already running deficits, and face even larger ones in the coming months? The federal government will have a huge deficit during the next year, perhaps a trillion dollars, because of the $700 billion bailout, the stimulus package, and the expected sharp declines in tax revenues.

A serious recession will certainly lead to increased regulation of business and labor markets. Some greater regulation of financial markets would certainly be desirable, as I have argued in prior posts, but some of the likely new regulations will be harmful, such as greater protectionism, wage-type controls over income of top executives, higher taxes on capital gains, and others.

The decline in oil prices by over 50 percent to $60 or less a barrel will certainly help American consumers and companies since the US imports about 2/3 of the oil it uses. It is also helpful to American interests to have less revenue flowing to Venezuela, Russia, and some of the Middle Eastern countries. On the other hand, the US is a major exporter of grains and beef, and the decline in their prices will cause considerable problems for farmers. On balance, I believe the decline in commodity prices is a plus for the US, but not a huge one, especially if oil prices begin to rise sharply after the world recession is over.

A serious recession will further erode the pay and bonuses of top executives at financial and other companies, which many will be happy to see. Managers of mutual and hedge funds and investment banks may have been making much more money than is justified by their productivity, but surely the misery inflicted on the lesser skilled workers, low income families, poor homeowners, and other economically weaker groups is not worth any benefits from a sharp fall in the incomes of those at the top.

So my bottom line in discussing the question whether depressions have a silver lining is that any such lining is very thin and small compared to the major costs to households, workers, and small businessmen.

Moral hazard is everywhere

The recent plan to modify mortgage terms for people who can’t pay may trigger bigger default as everybody wants to get a cut from the bailout (source: wsj)

Another day, another bailout: This time homeowners get to benefit from mortgage-modification programs, designed to stem the tide of foreclosures by making it easier for borrowers to stay current on their loans.

But the latest plans from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, joining banks such as J.P. Morgan Chase and Citigroup, hold plenty of risks.

Take investors in mortgage-backed securities. Modifications to mortgage holders’ interest rates could leave some MBS holders with reduced interest payments. Forgiveness of principal, meanwhile, could lead to capital losses.

A bigger worry could be that these modification programs are too effective. In that case, “many current borrowers will wave the white flag of surrender and also try to get a modification,” Rod Dubitsky, a senior strategist for asset-backed securities at Credit Suisse, wrote in a recent report.

The danger is that loan holders who otherwise could meet their payments would decide to fall behind to get their cut of the bailout. That could unleash a chain reaction that drives default rates even higher.

That means another dose of moral hazard. Federal officials stopped worrying months ago about that for companies, as they piled up bailout upon bailout to keep the financial system from collapsing. Now officials risk injecting warped incentives into the behavior of individuals.

If the programs take pressure off house prices, MBS holders and borrowers could both make out better than if there weren’t any modifications.

But the financial crisis has shown time and again that it is tough to anticipate the unintended consequences resulting from attempts to quell the turmoil.

Watch this CNBC video to get more out of the modification plan.

Markowitz on thinking about portfolio theory in crisis

From Wall Street Journal. The highlights are mine.

The Father of Portfolio Theory on the Crisis

In the early 1950s, when young Harry Markowitz was looking for an area of economics to pursue, a chance encounter with a stockbroker in Chicago led him to apply a new logic about risk to what had been an investment industry based on touting individual stocks. He revolutionized the investing world by showing how to create diversified portfolios that reduce risk and maximize return.

Our current credit crisis arose from an imbalance of risk and return in portfolios of mortgage-backed and other debt securities, so it seems timely to ask the father of modern finance what went wrong and what to do about it.

Now 81 and still teaching and advising funds, Mr. Markowitz has good news and bad news. The bad news is that bailouts to restore liquidity aren't addressing the real problem. The good news is that once we have the information to measure the losses of bad risk-taking, markets will recover.

Mr. Markowitz doesn't excuse the financial engineers who bundled complex mortgage-based and other securities. They violated the first principle of his portfolio theory. "Diversifying sufficiently among uncorrelated risks can reduce portfolio risk toward zero," he says in an interview. "But financial engineers should know that's not true of a portfolio of correlated risks."

In traditional Markowitz-inspired investing, such as mutual funds and index funds, there is a discipline around variables such as asset classes and models of covariance. In contrast, collateralized mortgage obligations and related securities had no such discipline. These risks sank together. "Selling people what sellers and buyers don't understand," he says with understatement, "is not a good thing."

In a now-famous paper on portfolio selection in the Journal of Finance in 1952, Mr. Markowitz wrote that risks that are not correlated with one another work best, while investments that move together — owning both Ford and GM — are riskier. This idea, which seems obvious now, was so novel then that when Milton Friedman reviewed Mr. Markowitz's University of Chicago Ph.D. dissertation, he half-joked it couldn't lead to a degree in economics because the topic was not economics. Mr. Markowitz got the degree and in 1990 shared the Nobel Prize in economics for portfolio theory.

As with all new information tools at our disposal, applying portfolio theory to investing entails its share of trial and error. Mr. Markowitz admits some people might object to asking him how to repair the credit crisis. "You, Harry Markowitz, brought math into the investment process," he imagines some people thinking. "It is fancy math that brought on this crisis. What makes you think now that you can solve it?"

He draws a line between his portfolio theory and its later misapplication. "Not all financial engineering is always bad," he says, "but the layers of financially engineered products of recent years, combined with high levels of leverage, have proved to be too much of a good thing." In contrast, classic investment portfolios such as mutual funds and index funds continue to reduce risk.

In an essay recently posted on the Web site of Index Funds Advisors titled "What to Do About the Financial Transparency Crisis," Mr. Markowitz calls for urgency in addressing the underlying problem of mismatched securities. So long as there is continued "obscurity of billions of dollars of financial instruments," we run the risk of Japan-style stagnation. Banks there, with the support of the Ministry of Finance, refused to mark bad debts to market for a decade.

"Just as with all securities, the fundamental exercise of the analysis and understanding of the trade-off between risk and return has no shortcuts," Mr. Markowitz says. "Arbitrarily assigning expected returns absent an understanding of the risks of the securities is precisely how the economy arrived at this point."

Mr. Markowitz reckons it could take a year before we have the transparency we need. Assessing the value of mortgage-backed securities requires scrutinizing mortgages down to the level of individual ZIP Codes. "The valuation process will take as long as it takes, but it is the primary step toward effectively utilizing the very controversial bailout and avoiding the structural problem of a stagnant economy."

How to avoid more such crises? Politicians need to learn a lesson. "If the choice is requiring mortgages for people who don't qualify or keeping the banking system sound, we should learn to opt for sound banking every time," he says. Also, since "financial engineers seem to get their necks chopped off periodically," they shouldn't get bailed out when it happens.

The father of modern finance knows how badly correlated portfolios create risk instead of controlling risk. Mr. Markowitz deserves a hearing from policy makers for his insistence that they focus on restoring information and transparency to the credit markets, making losses clear and resetting prices accordingly. To put the issue in probability terms, the odds are between very remote and nonexistent that the economy can recover until these basic steps are taken.

Morgan Stanley says Euro breakup is not impossible but unlikely

Morgan Stanley entertains the possibility of a breakup of Euro. Some good analysis.