Thomas Friedman: Real Engineering vs. Financial Engineering

Green the Bailout

Many things make me weep about the current economic crisis, but none more than this brief economic history: In the 19th century, America had a railroad boom, bubble and bust. Some people made money; many lost money. But even when that bubble burst, it left America with an infrastructure of railroads that made transcontinental travel and shipping dramatically easier and cheaper.

The late 20th century saw an Internet boom, bubble and bust. Some people made money; many people lost money, but that dot-com bubble left us with an Internet highway system that helped Microsoft, I.B.M. and Google to spearhead the I.T. revolution.

The early 21st century saw a boom, bubble and now a bust around financial services. But I fear all it will leave behind are a bunch of empty Florida condos that never should have been built, used private jets that the wealthy can no longer afford and dead derivative contracts that no one can understand.

Worse, we borrowed the money for this bubble from China, and now we have to pay it back — with interest and without any lasting benefit.

Yes, this bailout is necessary. This is a credit crisis, and credit crises involve a breakdown in confidence that leads to no one lending to anyone. You don’t fool around with a credit crisis. You have to overwhelm it with capital. Unfortunately, some people who don’t deserve it will be rescued. But, more importantly, those who had nothing to do with it will be spared devastation. You have to save the system.

But that is not the point of this column. The point is, we don’t just need a bailout. We need a buildup. We need to get back to making stuff, based on real engineering not just financial engineering. We need to get back to a world where people are able to realize the American Dream — a house with a yard — because they have built something with their hands, not because they got a “liar loan” from an underregulated bank with no money down and nothing to pay for two years. The American Dream is an aspiration, not an entitlement.

When I need reminding of the real foundations of the American Dream, I talk to my Indian-American immigrant friends who have come here to start new companies — friends like K.R. Sridhar, the founder of Bloom Energy. He e-mailed me a pep talk in the midst of this financial crisis — a note about the difference between surviving and thriving.

“Infants and the elderly who are disabled obsess about survival,” said Sridhar. “As a nation, if we just focus on survival, the demise of our leadership is imminent. We are thrivers. Thrivers are constantly looking for new opportunities to seize and lead and be No. 1.” That is what America is about.

But we have lost focus on that. Our economy is like a car, added Sridhar, and the financial institutions are the transmission system that keeps the wheels turning and the car moving forward. Real production of goods that create absolute value and jobs, though, are the engine.

“I cannot help but ponder about how quickly we are ready to act on fixing the transmission, by pumping in almost one trillion dollars in a fortnight,” said Sridhar. “On the other hand, the engine, which is slowly dying, is not even getting an oil change or a tuneup with the same urgency, let alone a trillion dollars to get ourselves a new engine. Just imagine what a trillion-dollar investment would return to the economy, including the ‘transmission,’ if we committed at that level to green jobs and technologies.”

Indeed, when this bailout is over, we need the next president — this one is wasted — to launch an E.T., energy technology, revolution with the same urgency as this bailout. Otherwise, all we will have done is bought ourselves a respite, but not a future. The exciting thing about the energy technology revolution is that it spans the whole economy — from green-collar construction jobs to high-tech solar panel designing jobs. It could lift so many boats.

In a green economy, we would rely less on credit from foreigners “and more on creativity from Americans,” argued Van Jones, president of Green for All, and author of the forthcoming “The Green Collar Economy.” “It’s time to stop borrowing and start building. America’s No. 1 resource is not oil or mortgages. Our No. 1 resource is our people. Let’s put people back to work — retrofitting and repowering America. … You can’t base a national economy on credit cards. But you can base it on solar panels, wind turbines, smart biofuels and a massive program to weatherize every building and home in America.”

The Bush team says that if this bailout is done right, it should make the government money. Great. Let’s hope so, and let’s commit right now that any bailout profits will be invested in infrastructure — smart transmission grids or mass transit — for a green revolution. Let’s “green the bailout,” as Jones says, and help ensure that the American Dream doesn’t ever shrink back to just that — a dream.

Eichengreen: Fed Groping In the Dark

A couple of months ago at lunch with a respected Fed watcher, I asked, “What are the odds are that US unemployment will reach 10% before the crisis is over?” “Zero,” he responded, in an admirable display of confidence. Watchers tending to internalise the outlook of the watched, I took this as reflecting opinion within the US central bank. We may have been in the throes of the most serious credit crisis since the Great Depression, but nothing resembling the Depression itself, when US unemployment topped out at 25%, was even remotely possible. The Fed and Treasury were on the case. US economic fundamentals were strong. Comparisons with the 1930s were overdrawn.

The events of the last week have shattered such complacency. The 3 month treasury yield has fallen to “virtual zero” for the first time since the flight to safety following the outbreak of World War II. The Ted Spread, the difference between borrowing for 3 months on the interbank market and holding three month treasuries, ballooned at one point to five full percentage points. Interbank lending is dead in its tracks. The entire US investment banking industry has been vaporised.

And we are in for more turbulence. The Paulson Plan, whatever its final form, will not bring this upheaval to an early end. The consequences are clearly spreading from Wall Street to Main Street. The recent performance of nonfinancial stocks indicates that investors are well aware of the fact.

So comparisons with the Great Depression, which have been of academic interest but little practical relevance, take on new salience. Which ones have content, and which are mainly useful for headline writers?

First, the Fed now, like the Fed in the 1930s, is very much groping in the dark. Every financial crisis is different, and this one is no exception. It is hard to avoid concluding that the Fed erred disastrously when deciding that Lehman Bros. could safely be allowed to fail. It did not adequately understand the repercussions for other institutions of allowing a primary dealer to go under. It failed to fully appreciate the implications for AIG’s credit default swaps. It failed to understand that its own actions were bringing us to the brink of financial Armageddon.

If there is a defence, it has been offered Rick Mishkin, the former Fed governor, who has asserted that the current shock to the financial system is even more complex than that of the Great Depression. There is something to his point. In the 1930s the shock to the financial system came from the fall in the general price level by a third and the consequent collapse of economic activity. The solution was correspondingly straightforward. Stabilise the price level, as FDR did by pumping up the money supply, and it was possible to stabilise the economy, in turn righting the banking system.

Absorbing the shock is more difficult this time because it is internal to the financial system. Central to the problem are excessive leverage, opacity, and risk taking in the financial sector itself. There has been a housing-market collapse, but in contrast to the 1930s there has been no general collapse of prices and economic activity. Corporate defaults have remained relatively low, which has been a much-needed source of comfort to the financial system. But this also makes resolving the problem more difficult. Since there has been no collapse of prices and economic activity, we are not now going to be able to grow or inflate our way out of the crisis, as we did after 1933.

In addition, the progress of securitisation complicates the process of unravelling the current mess. In the 1930s the Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation bought individual mortgages to cleanse bank balance sheets and provide home owners with relief. This time the federal agency responsible for cleaning up the financial system will have to buy residential mortgage backed securities, collateralised debt obligations, and all manner of sliced, diced and repackaged paper. Strengthening bank balance sheets and providing homeowners with relief will be infinitely more complex. Achieving the transparency needed to restore confidence in the system will be immensely more difficult.

That said, we are not going to see 25% unemployment rates like those of the Great Depression. Then it took breathtaking negligence by the Fed, the Congress and the Hoover Administration to achieve them. This time the Fed will provide however much liquidity the economy needs. There will be no tax increases designed to balance the budget in the teeth of a downturn, like Hoover’s in 1930. Where last time it took the Congress three years to grasp the need to recapitalise the banking system and provide mortgage relief, this time it will take only perhaps half as long. Ben Bernanke, Hank Paulson and Barney Frank are all aware of that earlier history and anxious to avoid repeating it.

And what the contraction of the financial services industry taketh, the expansion of exports can give back, what with the continuing growth of the BRICs, no analogue for which existed in the 1930s. The ongoing decline of the dollar will be the mechanism bringing about this reallocation of resources. But the US economy, notwithstanding the admirable flexibility of its labour markets, is not going to be able to move unemployed investment bankers onto industrial assembly lines overnight. I suspect that I am now less likely to be regarded as a lunatic when I ask whether unemployment could reach 10%.

Fed Balance Sheet: then and now

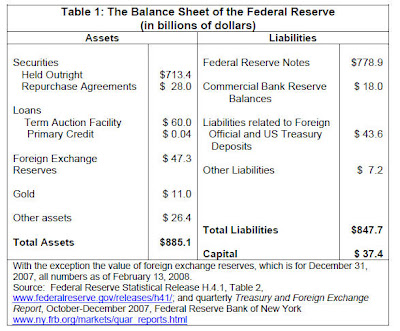

First, a review of the Fed balance sheet back in February (courtesy of Steve Cecchetti):

The Fed balance sheet now (as of Sept. 24, 2008, my own calculation):

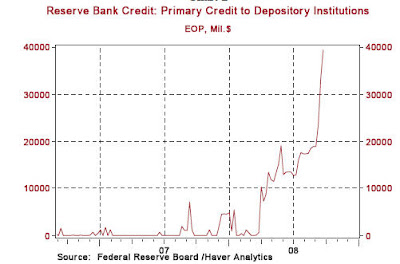

Fed's balance sheet increased from $885 billion to $1,214 billion, a jump of 37%. So far, we haven't seen much money-printing: the Fed reserve notes (the fiat money) just increased from $779 billion to $799 billion. But the composition of Fed's asset holdings worsened, as highlighted in red. The Fed put too much bank junks onto its balance sheet.

Below three extra graphs are taken out from Northern Trust research team, demonstrating the effect in a more dramatic fashion.

Harvard Panel on Current Financial Crisis

McArthur University Professor Robert Merton, a 1997 Nobel laureate in economics for his work on options pricing and risk analysis, advanced the importance of "functional analysis of the financial system." (His experience with the system is both theoretical and actual; he was a principal in Long Term Capital Management, the extraordinarily leveraged investment firm whose collapse in 1998 nearly precipitated a world financial crisis and necessitated a bailout negotiated by the Federal Reserve; see a review of books on that precursor of the current situation here).

Although current concerns focus on liquidity and the credit markets, Merton said, it was essential to note that as too-high housing prices deflated, perhaps $3 trillion to $4 trillion of actual wealth had been lost in the last year alone—and was unlikely to return. With each successive decline in the value of an asset held on a leveraged basis, he said, an owner's effective risk and effective leverage ramped up at an accelerating rate, underlining the destruction of the financial institutions that held the underlying failed mortgage loans and securities based on them. In addition, such deterioration prompts "feedback": for instance, banks and thrift institutions held Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac preferred stock as part of their presumably safest, most reliable capital; when the government took control of those institutions, the banks' and thrifts' capital absorbed immediate, large losses—instantly increasing their own leverage and decreasing their ability to make loans, worsening the underlying housing crisis.

Financial innovation and "engineering" are widely blamed for causing, or worsening, the current crisis, and in a sense, they have, Merton said. Innovations inherently involve the risk that some ideas will fail, and inherently outrun existing regulatory structures. But rather than clamping down so severely that financial innovation is choked off, he argued that regulation must allow for further, future innovation as an engine of growth, because the functional needs—consumers' need to finance their retirements, developing nations' ability to fund economic development—remain intact. Thus, he urged that the focus remain on the necessary financial functions, and not on saving any particular form of institution that currently meets those needs, or did until recently.

Jobs in finance, he told the anxious M.B.A.s, would be "tough" to come by. But the solution for society would not be to rid financial institutions of highly trained, innovation-oriented financial engineers. Rather, he insisted, management teams, boards of directors, and regulators needed much more such expertise in their own ranks so they could understand the products they were offering and acquiring—as they so apparently did not in the recent past.

~~~~~

Beren professor of economics N. Gregory Mankiw, who teaches the perennially popular Economics 10 introductory course and and is the author of the core introductory textbook in the field, said that "the basic problem facing the financial system is that lots of people made very big bets that housing prices could not fall 20 percent," despite evidence to the contrary in the Great Depression and more recently in Japan. The resulting losses wouldn't matter in classical economic theory, he said—taking risk entails absorbing loss—except that the simultaneous large bets undercut much of the financial system all at once, and that system, as readers of his textbook know, is vital for the economy as a whole. Federal Reserve chairman Ben S. Bernanke '75 (access his June Commencement address here) focused on just this problem in his examination of the role of bank failures in worsening the Great Depression, Mankiw noted.

How should one view the proposed $700-billion federal financing initiative, Mankiw asked. One theory, advanced by President George W. Bush the night before, was that financial institutions' damaged assets have value greater than their current price, and only the federal government has the resources to buy and hold them to maturity. Wall Street economists, Mankiw said, like that interpretation. Their (tenured) academic counterparts are skeptical: the Treasury, they say, will overpay, thus bailing out failed managers who don't deserve it; and/or the funds will be insufficient to recapitalize banks, given the real magnitude of the losses they face.

Academic economists' alternatives are three: let the market handle the situation (as hedge funds and private-equity funds step forward where they see attractive opportunities to invest fresh capital); have the government somehow take equity positions in troubled banks and other institutions, directly infusing them with capital but benefiting as they recover (much as investor Warren Buffett put $5 billion into Goldman Sachs, with the right to invest $5 billion more on favorable terms); or force banks to raise capital, no matter what (in the friendly manner, Mankiw suggested, of a Mafia enforcer dropping by for a chat with management).

As for the presidential candidates, Mankiw said, Barack Obama, J.D. '91, seemed to be saying that the market had run wild, inflicting on the public the downside of unfettered capitalism. Recalling his service from 2003 to 2005 as chair of the president's Council of Economic Advisers, Mankiw said that he had tried to rein in the government-sponsored Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Predecessors in the Clinton administration, he said, found the task impossible, too. This was a known "time bomb," he said, not a market problem. Nor was it simply a problem of lax underwriting standards for loans.

Of John McCain's emphasis on Wall Street "greed" and "corruption," Mankiw said, there was scant evidence that corruption was the problem. Many people made ill-advised bets, he said, but that was not criminal. And he suspected that greed would be a factor in the markets that any future administration would encounter.

~~~~~

Cabot professor of public policy Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist and director of research for the International Monetary Fund, tried to put the "truly incredible" recent developments in some larger context.

The financial sector of the economy, he said, had become "bloated"—accounting for 7 to 8 percent of jobs (including insurance employees), but capturing 10 percent of wages and 30 percent of profits. Such evidently huge returns naturally attracted torrents of new investment, making the financial sector as a whole a bubble: "It is too big, it is not sustainable, it has to shrink" even beyond its already depleting ranks. The problem, he said, is not merely bad debts held by institutions, but "bad banks" themselves: the whole sector of financial enterprises begs to be restructured. (Rogoff noted that he had for several months forecast the collapse of at least one large investment bank, but even he was surprised at the near-collapse of nearly all the principal investment banks virtually overnight.)

Much as auto makers or steel companies in the past argued that they were basic to the economy and therefore required federal support, he said, today the "country is being ransomed by the financial sector" in the demand for the $700-billion bailout, which would have the effect of maintaining management salaries, bidding up the prices of stock and bond holdings in their companies' portfolios, and so on. Today, unlike during the Great Depression, Rogoff argued, the shrinkage of such institutions would be "not unproductive" for the economy as a whole. (As an aside, he noted that all those Harvard students who marched off to investment banking "will be freed to go into other activities.") Given the difficulties of conducting auctions to buy distressed assets with the government's largess without letting excess funds leak back into the financial sector, Rogoff was sympathetic with Warren's argument for focusing on the needs of homeowners.

In international perspective, he said, the United States "has been running spectacular deficits" for 15 years or more. The availability of foreign funds has enabled the country to keep interest rates low—maintaining abundant liquidity—but has exposed the fragility of the system if federal budget deficits balloon. In the present instance, he said, the issue becomes a question of whether Beijing wishes to lend the United States $700 billion to repair American financial institutions. Americans aren't immediately going to be the source of those funds, he noted: "We're supposed to keep consuming." In other words, the country is saying, "We borrowed too much, we screwed up, so we're going to fix it by borrowing more."

He said a better strategy was required—but not at the expense of excessive regulation that would choke off innovation, one of the few flagships of American economic growth and strength in recent decades (a point also made by Merton at HBS on September 23, and again after Rogoff's presentation). After the dot.com bust of 2000-2001, Rogoff said, the technology sector regained its footing. Today, it is equally important not to overreact, so that a dynamic financial sector, corrected by "tough love," can resume its proper and important role in the economy and in future growth.

Get the auction right!

Thee Treasury proposes to invest $700 billion in mortgage-related securities to resolve the financial crisis, using market mechanisms such as reverse auctions to determine prices. A well-designed auction process can indeed be an effective tool for acquiring distressed assets at minimum cost to the taxpayer. However, a simplistic process could lead to higher cost and fewer securities purchased. It is critical for the auction process to be designed carefully.

The immediate crisis is one of illiquidity. Banks hold a variety of mortgage-backed securities, some almost worthless while other retain considerable value. None can be sold, except at fire-sale prices. The Treasury proposes to restore liquidity by stepping in and purchasing these securities. But at what price?

A simple approach leads to overpayment

A simple but naïve approach would be to invite the holders of all mortgage-related securities to bid in a single reverse auction. The Treasury sets an overall quantity of securities to be purchased. The auctioneer starts at a price of nearly 100 cents on the dollar. All holders of illiquid securities would presumably be happy to sell at nearly face value, so there would be excess supply. The auctioneer then progressively lowers the price—90 cents, 80 cents, etc.—and bidders indicate the securities that they are willing to sell at each lower price. Eventually, a price, perhaps 30 cents, is reached at which supply equals demand. The Treasury buys the securities offered at the clearing pricing, paying 30 cents on the dollar.

This simplistic approach is fatally flawed. The Treasury pays 30 cents on the dollar, purchasing all mortgage-related securities worth less than 30 cents on the dollar. Perhaps, on average, the purchased securities are worth 15 cents on the dollar. The Treasury buys only the worst of the worst, intervening in a way that rewards the least deserving. And, as a result of overpaying drastically, the Treasury can mop up relatively few distressed securities with its limited budget.

In the simplistic approach, competition among different securities overshadows competition within securities and among bidders. The auction merely identifies which securities are least valuable, rather than determining the securities' value. An auction that determines a real price for a given security needs to require multiple holders of the security to compete with one another. This can be achieved if the Treasury purchases only some, not all, of any given security.

A better approach

Thus, a better approach would be for the Treasury to instead conduct a separate auction for each security and limit itself to buying perhaps 50% of the aggregate face value. Again, the auction starts at a high price and works its way down. If the security clears at 30 cents on the dollar, this means that the holders value it at 30 cents on the dollar. (If the value were only 15 cents, then most holders would supply 100% of their securities to be purchased at 30 cents, and the price would be pushed lower.) The auction then works as intended. The price is reasonably close to value. The "winners" are the bidders who value the asset the least and value liquidity the most.

This auction has an important additional benefit. The "losers" are not left high and dry. By determining the market clearing price, the auction increases liquidity for the remaining 50% of face value, as well as for related securities. The auction has effectively aggregated market information about the security's value. This price information is the essential ingredient needed to restore the secondary market for mortgage backed securities.

Handling many securities is a straightforward extension. Different but related securities can be grouped together in the same auction and purchased simultaneously. Each security has its own price. The bidders indicate the quantity of each security they would like to sell at the specified prices. The price is reduced for any security with excess supply and the process repeats until a clearing price is found for each security. Auctioning many related securities simultaneously gives the bidders some flexibility to adjust positions as the market gradually clears. This improves price formation and enables bidders to better manage their liquidity needs. As a result, efficiency improves and taxpayer costs are further reduced.

For this auction design to work well, there needs to be sufficient competition. This should not be a problem for securities with diffuse ownership. For securities with more concentrated ownership, various approaches are possible. The Treasury could buy a smaller percentage of the face value. Alternatively, the Treasury could purchase the securities with the explicit understanding that the securities would be sold by auction some months or years in the future, after the liquidity crisis is over. To the extent that the securities are sold at a lower price, the holder would contractually owe the Treasury the difference, plus interest.

One sensible approach for the sequencing of auctions is to start with the best of the worst; that is, begin the auctioning with a group of securities that are among the least toxic. These will be easier for bidders to assess, and the auction can proceed more quickly. Then, subsequent auctions can move on to the increasingly problematic securities. In this way, the information revealed in the earlier auctions will facilitate the later auctions.

The basic auction approach suggested here is neither new nor untested. It was introduced over the last ten years and has been used successfully in many countries to auction tens of billions of dollars in electricity and gas contracts. It is quite similar to the approach that has been used to auction more than $100 billion in mobile telephone spectrum worldwide. It is a dynamic version of the approach that financial markets use for share repurchases. If implemented correctly, each auction can be completed in less than one day.

Thus, the auction approach meets the three main requirements of the rescue plan:

1) provide a quick and effective means for the Treasury to purchase mortgage-related assets and increase liquidity;

2) yield prices that are closely related to value; and

3) provide a transparent rules-based mechanism that treats different security holders consistently and leaves minimal scope for discretion or favoritism.

Indeed, the second and third requirements may be decisive for obtaining broad political support. The main alternative to auctions put forward by the Treasury is to employ professional asset managers. To the extent that negotiations or other individualized trading arrangements are used, the public will be rightfully wary that favoritism may be exerted and that some security holders will be offered sweetheart deals. By contrast, a transparent auction process is readily subjected to oversight. The Treasury appears to be embarking on the greatest public intervention into financial markets since the Great Depression. The ultimate success or failure of the intervention may depend on the fine details of the auction design. Let's get it right.

Roach on Chinese Economy and Paulson’s Rescue Plan

Note: This is an audio clip about 20 mins.