Home » 2009 (Page 17)

Yearly Archives: 2009

Markets can be wrong and the price is not always right

Richard Thaler, professor at U. of Chicago, chastises the foundation of the modern finance, the Efficient Market Hypothesis (or EMH) (source: FT),

I recently had the pleasure of reading Justin Fox’s new book The Myth of the Rational Market . It offers an engaging history of the research that has come to be called the “efficient market hypothesis”. It is similar in style to the classic by the late Peter Bernstein, Against the Gods. All the quotes in this column are taken from it. The book was mostly written before the financial crisis . However, it is natural to ask if the experiences over the last year should change our view of the EMH.

It helps to start with a quick review of rational finance. Modern finance began in the 1950s when many of the great economists of the second half of the 20th century began their careers. The previous generation of economists, such as John Maynard Keynes, were less formal in their writing and less tied to rationality as their underlying tool. This is no accident. As economics began to stress mathematical models, economists found that the simplest models to solve were those that assumed everyone in the economy was rational. This is similar to doing physics without bothering with the messy bits caused by friction. Modern finance followed this trend.

From the starting point of rational investors came the idea of the efficient market hypothesis, a theory first elucidated by my colleague and golfing buddy Gene Fama. The EMH has two components that I call “The Price is Right” and “No Free Lunch”. The price is right principle says asset prices will, to use Mr Fama’s words “fully reflect” available information, and thus “provide accurate signals for resource allocation”. The no free lunch principle is that market prices are impossible to predict and so it is hard for any investor to beat the market after taking risk into account.

For many years the EMH was “taken as a fact of life” by economists, as Michael Jensen, a Harvard professor, put it, but the evidence for the price is right component was always hard to assess. Some economists took the fact that prices were unpredictable to infer that prices were in fact “right”. However, as early as 1984 Robert Shiller, the economist, correctly and boldly called this “one of the most remarkable errors in the history of economic thought”. The reason this is an error is that prices can be unpredictable and still wrong; the difference between the random walk fluctuations of correct asset prices and the unpredictable wanderings of a drunk are not discernable.

Tests of this component of EMH are made difficult by what Mr Fama calls the “joint hypothesis problem”. Simply put, it is hard to reject the claim that prices are right unless you have a theory of how prices are supposed to behave. However, the joint hypothesis problem can be avoided in a few special cases. For example, stock market observers – as early as Benjamin Graham in the 1930s – noted the odd fact that the prices of closed-end mutual funds (whose funds are traded on stock exchanges rather than redeemed for cash) are often different from the value of the shares they own. This violates the basic building block of finance – the law of one price – and does not depend on any pricing model. During the technology bubble other violations of this law were observed. When 3Com, the technology company, spun off its Palm unit, only 5 per cent of the Palm shares were sold; the rest went to 3Com shareholders. Each shareholder got 1.5 shares of Palm. It does not take an economist to see that in a rational world the price of 3Com would have to be greater than 1.5 times the share of Palm, but for months this simple bit of arithmetic was violated. The stock market put a negative value on the shares of 3Com, less its interest in Palm. Really.

Compared to the price is right component, the no free lunch aspect of the EMH has fared better. Mr Jensen’s doctoral thesis published in 1968 set the right tone when he found that, as a group, mutual fund managers could not outperform the market. There have been dozens of studies since then, but the basic conclusion is the same. Although there are some anomalies, the market seems hard to beat. That does not prevent people from trying. For years people predicted fees paid to money managers would fall as investors switched to index funds or cheaper passive strategies, but instead assets were directed to hedge funds that charge very high fees.

Now, a year into the crisis, where has it left the advocates of the EMH? First, some good news. If anything, our respect for the no free lunch component should have risen. The reason is related to the joint hypothesis problem. Many investment strategies that seemed to be beating the market were not doing so once the true measure of risk was considered. Even Alan Greenspan, the former Federal Reserve chairman, has admitted that investors were fooled about the risks of mortgage-backed securities.

The bad news for EMH lovers is that the price is right component is in more trouble than ever. Fischer Black (of Black-Scholes fame) once defined a market as efficient if its prices were “within a factor of two of value” and he opined that by this (rather loose) definition “almost all markets are efficient almost all the time”. Sadly Black died in 1996 but had he lived to see the technology bubble and the bubbles in housing and mortgages he might have amended his standard to a factor of three. Of course, no one can prove that any of these markets were bubbles. But the price of real estate in places such as Phoenix and Las Vegas seemed like bubbles at the time. This does not mean it was possible to make money from this insight. Lunches are still not free. Shorting internet stocks or Las Vegas real estate two years before the peak was a good recipe for bankruptcy, and no one has yet found a way to predict the end of a bubble.

What lessons should we draw from this? On the free lunch component there are two. The first is that many investments have risks that are more correlated than they appear. The second is that high returns based on high leverage may be a mirage. One would think rational investors would have learnt this from the fall of Long Term Capital Management, when both problems were evident, but the lure of seemingly high returns is hard to resist. On the price is right, if we include the earlier bubble in Japanese real estate, we have now had three enormous price distortions in recent memory. They led to misallocations of resources measured in the trillions and, in the latest bubble, a global credit meltdown. If asset prices could be relied upon to always be “right”, then these bubbles would not occur. But they have, so what are we to do?

While imperfect, financial markets are still the best way to allocate capital. Even so, knowing that prices can be wrong suggests that governments could usefully adopt automatic stabilising activity, such as linking the down-payment for mortgages to a measure of real estate frothiness or ensuring that bank reserve requirements are set dynamically according to market conditions. After all, the market price is not always right.

Uneven "recovery" in housing

Distressed sales now make up around two-thirds of transactions in Las Vegas and Miami; even in midwest area, where housing had relatively less drop, 39% of mortgage owners have negative equity (or underwater). At last, the market for the more expensive houses (500K and above) is simply not moving. It looks like still too early for housing recovery. (source: WSJ)

The U.S. housing market was unified by the bust. After peaking in 2006, home prices across the country joined the march downward. Are investors prepared for a return to more normal times?

It wasn't long ago that a nationwide price decline was considered almost impossible by many, not having been observed since the Great Depression. Supply and demand have usually dictated prices on a local level.

And yet, now that there are signs of stabilization, some investors appear to be hoping for prices to recover across the board. Better housing data, such as a rise in the S&P/Case-Shiller index have helped stocks extend a heady rally. A one-time government tax deduction for first time buyers and seasonal demand for homes have added a timely boost.

But a look on a regional level shows a different story. The likes of overbuilt Las Vegas and Miami have yet to see prices turn. There, distressed sales now make up around two-thirds of transactions, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Such distressed sales, mainly foreclosures, are discounted on average 15% to 20%, dragging overall prices lower. Granted, that may set the stage for higher prices when foreclosures slow, but there still is little sign that inventory is near equilibrium.

On the face of it, other parts of the country appear to have better traction. Take the Midwest. Cleveland saw prices rise 10% in the three months through June, the fastest of any location in S&P/Case Shiller's 20-city index.

Midwestern states will likely face some hiccups in any recovery. The NAR reckons the Midwest still has 8.0 months' supply of single-family homes on the market between $100,000 and $250,000, compared with 8.9 months a year ago. During the 1990s, the average nationwide was 6.6 months.

That supply could be tough to clear. The many buyers underwater on existing homes will struggle to move, even to a cheaper home. In Ohio, for instance, some 39% of mortgages have negative equity, or are attached to properties worth less than outstanding debt, according to research firm First American CoreLogic. The national average is 32%.

Demand may stay especially weak for homes in high price categories. The NAR says just 2.5% of the 460,000 homes sold in July cost $500,000 or more. In the fourth quarter of 2004, such homes accounted for 11.2% of the total.

That presents potential for higher average sales prices if more high-end sales are completed. But, with "jumbo" mortgages harder to come by, demand is likely to remain concentrated at lower price levels.

Of course, stability in some housing markets is refreshing. But after the summer house-hunting season ends, the sum of a fragmented market is unlikely to be a unified rise.

Treasuries or gold?

Which is a better investment, under different scenarios? WSJ analyzes:

Is the outlook for the world economy dark enough for gold to continue to glitter?

Remarkably, the gold price has appreciated 12% since April, a period during which financial-meltdown fears appear to have receded and investors have rushed back into riskier assets. Gold's resilience suggests continuing demand for an asset that could outperform in worst-case scenarios.

But not every difficult economic outcome is the same. That is something investors need to remember as they decide whether gold — rather than Treasurys — really is the best disaster hedge.

Treasurys start with several advantages. They produce an income stream, whereas gold doesn't. And, although Treasurys would be hit if there is a strong economic rebound with low inflation, gold would likely be hammered.

Next, Treasurys actually did better than gold in the fear-drenched period at the end of last year. The Merrill Lynch price index for the 10-year Treasury jumped 11.6% from September through the end of 2008. The Comex gold price was up 6.6% over the same period, and it sold off sharply in the middle of the meltdown. That last fact suggests gold benefits when markets are functioning — like now — but the metal, like other assets, can fall when markets close down.

In other words, Treasurys could trump gold in a Japan-like environment, where deflation pushes up real yields but isn't high enough to cause serious stress on the financial system and the wider economy.

But gold has a big friend in Western central banks, especially the Federal Reserve, which is still printing enormous amounts of dollars to support key markets. This makes the inflation outlook uncertain, helping gold and hurting currencies like the dollar.

The printing looks set to continue. Ominously, this weekend, the G-20 said central-bank liquidity support "will need to remain in place for some time."

One area where that support could stay in place for a long time is for the U.S. housing market. Right now, there is almost no private-sector demand for nonconforming residential mortgages, reflected in the fact that the U.S. government has effectively or explicitly guaranteed as much as 85% of all mortgages originated this year, according to Inside Mortgage Finance. In turn, the Fed is buying nearly 80% of government-backed mortgages packaged in securities. If it pulls back, house prices could resume their slide, triggering more foreclosures and losses for banks.

Finally, soaring fiscal deficits favor gold. The IMF expects G-7 countries to show a combined fiscal deficit equivalent to 10.36% of GDP this year, more than double the level following the 1990-91 recession. True, it is impossible to time a fiscal Armageddon bet. The yen has stayed strong even as Japanese government borrowing has exploded over the past 20 years.

But government finances are now deteriorating in most developed countries.

For pessimists, if we're in for a Japanese-style deflationary bust, buy Treasurys. For other disaster scenarios, go for gold.

How big is China’s Green Energy

Source: BoFIT

Although the relative share of electrical power generated by renewable energy systems is still small in China, the country has made remarkable progress in adopting new approaches in recent years. The amount of wind-generated electricity quadrupled between 2006 and 2008, and today China has the world’s fourth largest wind power generation capacity after the US, Germany and Spain. Large dam projects have also helped double hydro-power generation since 2002. Solar power use has increased dramatically along with incentives such as direct subsidies to e.g. building owners who install solar panels on their buildings. Moreover, China is planning to construct one of the world’s largest solar fields in Inner Mongolia.

The introduction of renewable power technologies has not been without difficulties. Despite state support for construction of wind farms, companies that operate the electricity grid have little incentive bring wind farms, which are often located in remote areas, onto the grid. By some estimates, as much as 20 % of wind power currently generated in China is still off-grid and capacity utilization of wind farms has been lower than expected. There have also been problems with hydro-power projects as China struggles with droughts and uncertainty over the long-term environmental impacts of huge dams.

Despite the rapid rise of sustainable energy systems, they still generate a small share of China’s total electricity (see chart). Hydro-power accounts for 16 % of electrical power generation, and wind just 0.4 %. Coal, in contrast is the basis of more that 80 % of China’s power generation. China’s goal is to raise the share of electricity generated by renewable systems to over 20 % by 2020.

China is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide. A substantial amount of these emissions are generated by coal-burning power plants. China’s future energy production will continue to rely heavily on coal-fired power plants and China has not committed to Kyoto treaty emission targets. International climate talks will continue in December at the Climate Summit in Copenhagen.

China’s CO2 emissions should fall slightly as the country makes gains in energy efficiency and its worst-polluting coal-fired power plants are shut down. A target of the cur-rent five-year plan (2006–2010) is to reduce energy consumption by 20 % relative to China’s per capita GDP. Although progress towards this decrease has been achieved, it appears unlikely that the target will be met.

Although the state has passed an energy saving law and launched a raft of energy-saving programs, heavy regulation of electricity prices erodes the incentive to be energy efficient. Moreover, there has not been political enthusiasm for deregulation of energy prices.

China is trying very hard to diversify away from US dollar

There is not much China can do, but purchasing IMF notes is a good away to increase its influence on international monetary policy.

The Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Mr. Dominique Strauss-Kahn, and the Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China, Mr. Yi Gang, have signed an agreement under which the People’s Bank of China would purchase up to SDR 32 billion (around US$50 billion) in IMF notes.

The note purchase agreement is the first in the history of the Fund, and follows the endorsement by the Executive Board on July 1, 2009 of the framework for issuing notes to the official sector. The Chinese authorities had expressed their intention to invest up to US$50 billion in IMF notes in June (see Press Releases No. 09/204 and No. 09/248).

The agreement offers China a safe investment instrument. It will also boost the Fund’s capacity to help its membership — particularly the developing and emerging market countries — weather the global financial crisis, and facilitate an early recovery of the global economy.

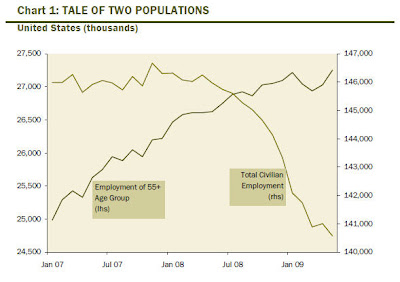

Shades of gray in employment

The unemployment rate is near 10%. Every age group is seeing decline of employment except for the age group that is above 55. What happened? This WSJ piece explains — It's not merely demographic change.

The Who famously sang they hoped they'd die before they got old. Clearly, they didn't want a proper job.

So far in this recession, 6.6 million jobs have been lost on a seasonally adjusted basis. That wipes out six of 10 jobs created in the last, unusually jobless, economic upswing. Every age group has lost jobs.

Except, that is, the cohort aged 55 and over, which has gained nearly one million positions. What's more, over-55s accounted for two-thirds of net jobs created in the upswing.

This has less to do with gray flair and more with a statistical wrinkle. The first of the postwar baby boomers hit official retirement age in 2011. That demographic bulge has been rolling through the age structure — in and out of the workplace — through this decade. According to Census Bureau estimates, the overall population age 55 to 64 grew by 9.4 million between July 2001 and July 2008. That isn't dissimilar to the roughly eight million increase in the ranks of employed over-55s between November 2001 and now.

But the figures point to more than just a demographic change. Over the same time period, the proportion of over-55s in employment rose five percentage points, possibly reflecting a need to re-enter the job market after the bursting of a tech bubble and a housing bubble damaged their net worth.

Meanwhile, labor participation fell for every other age group. For those age 16 to 24, for example, the rate fell almost 10 percentage points, to under half, even as that population group expanded. A graying work force focusing on rebuilding its nest egg while the young struggle for entry doesn't bode well for an economy dependent on sprightly consumers.

David Rosenberg also has a wonderful graph on this:

![[u.s. housing recovery]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AY587_Househ_NS_20090902182823.gif)

![[gold prices]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AY670_Goldhe_NS_20090908162141.gif)

![[job losses]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AY321_DEMONH_NS_20090818191526.gif)