Home » 2009 (Page 32)

Yearly Archives: 2009

Debt and inflation

Government and politicians have a tendency to use inflation to get out of their debt problem. Call it “debt monetization”. Here is a great chart from Casey’s Chart.

“The costs of things as measured by the consumer price index have risen twentyfold since the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. This act empowered the central bank to create and control a new currency for the United States, the Federal Reserve Note. Over this same period, the federal deficit soared from $2 billion to over $11 trillion. Coincidence? We think not.

After President Nixon cut the dollar’s ties to gold, funding the whims of government was no longer burdened by the need for higher taxes. Now any gaps in the budget can be filled by simply printing more dollars. And as you can see, the politicians didn’t hesitate to meet the challenge. Price levels and federal debt have risen hand-in-hand ever since.

The hidden tax of inflation has been stealing people’s buying power for nearly a century, but the opportunity to profit from it only comes about once every generation…”

US and global higher education boom

Following my previous post on China’s higher education boom/bubble, here I share with you another interesting research by Harvard labor economist Richard Freeman on how the global boom of higher education, especially in developing countries, has impacted on the US.

Exhibit 1 (all graphs are taken from Freeman’s NBER working paper) shows country’s share of global college enrollment.

In 2006, the US accounts for 12% of total college enrollment globally. But watch how China and India, the two most populous countries, how their college enrollments have soared over the years. China’s college enrollments rose from 1.7 million in 1980 to 23.4 million in 2006, or 16.5% of the world total.

A lot of college graduates from developing countries, seeking better opportunities, came to the United States. The chart below shows you the major source countries of international students in the US.

In the 2006-07 period, among 580K international students in the US, 2/3 are from Asia; 85% from developing countries: with India supplying the most, nearly 15%; China 12%; South Korea 10%. And nearly half (45%) of international students came to the US to pursue graduate degrees.

A lot of international students went to science & engineering (S&E) field. In 2005, 50.9% of PhD degrees in S&E were granted to foreign-born international students. If we just look at engineering, the number was at startling 69% (I believe the number is about the same in economics).

Focus on China: The number of students who came to the US to study and eventually got their PhD degrees in natural sciences has been rising sharply, especially after 1990s. (see graph below; the following graphs were taken from another NBER research by Bound, Turner & Walsh)

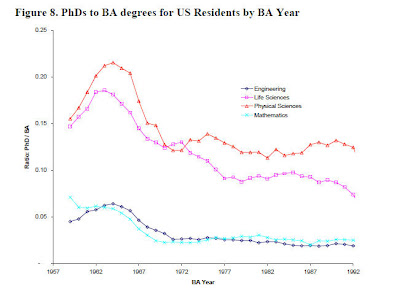

Meanwhile fewer and fewer US-born college graduates went to pursue PhD degrees. This is especially true in life sciences and physical sciences. I am not quite sure how this happened: it could be due to the education problem in US high school system; it could also be higher pay in other sectors, such as financials and investment banking.

But I suspect the surge of foreign PhDs in the US was largely a supply story. Why? The graph below looks at the correlation between the number of Bachelor degree holders and the PhD degrees granted in the US to foreign students. As you can see, there is an obviously strong positive correlation between the two.

Also, we have witnessed a cross-board surge of international students, almost in every field, not only in the science and engineering field.

Now we come to the policy delibrations.

With more and more PhD degrees granted to international students, foreign-born researchers and academics are sure to play a more and more important role in US higher education and research in coming years. A policy question naturally rises as to how to retain these foreign researchers. And what changes in US immigration policy should be in place to acheive the goal?

Marc Faber links inflation to pregnancy

A very interesting interview (with a lot of humor) of Dr. Marc Faber on the prospect of hyperinflation in the US.

He links inflation to pregnancy, “a little bit pregnant is as good as 100% pregnant”. A hilarious analogy! But he did raise a very intriguing question —why do economists unanimously think deflation is worse than inflation?

Watch part of the interview here on YouTube:

The sharp rising yield curve

The yield curve (the yield difference between 10-y and 2-y treasuries) has been rising sharply, to 2.75%, the highest level since Aug. 13, 2003.

Normally, rising yield curve signals economic recovery is well ahead. But the recent surge reflects probably much more of the market’s concern over government budget deficits and its ability to finance it. Either the government reins in spending, or the market will demand a higher interest rate as reflected in the rising yields of long-term government bonds.

Of course, government can always print money. So the alternative way of interpreting the current surge in the yield curve could be that the market is very nervous about higher inflation in the future so investors will demand the same real return on government bonds (nominal interest rate minus inflation).

(click to enlarge; source: calculatedrisk)

Also, with rising yield of 10-y treasury, the Fed’s effort in stimulating housing market through purchasing mortgage-backed securities will become less effective as the 30-year mortgage rates are closely tied to 10y treasury yields.

Regulation consensus

One such consensus is we need a regulator to look after the risks our financial system is taking as a whole. And what we need is not MORE regulation, but SMART regulation.

Watch this piece from David Wessel at Wall Street Journal:

John Taylor: Wake-up call for America

John Taylor at Stanford writes on Financial Times the recent downgrade of British sovereign debt is a wake-up call for America. He analyzes how the projected budget deficits of Obama Administration could lead to double digit inflation and sharp depreciation of the dollar, just like 1970s.

Standard and Poor’s decision to downgrade its outlook for British sovereign debt from “stable” to “negative” should be a wake-up call for the US Congress and administration. Let us hope they wake up.

Under President Barack Obama’s budget plan, the federal debt is exploding. To be precise, it is rising – and will continue to rise – much faster than gross domestic product, a measure of America’s ability to service it. The federal debt was equivalent to 41 per cent of GDP at the end of 2008; the Congressional Budget Office projects it will increase to 82 per cent of GDP in 10 years. With no change in policy, it could hit 100 per cent of GDP in just another five years.

“A government debt burden of that [100 per cent] level, if sustained, would in Standard & Poor’s view be incompatible with a triple A rating,” as the risk rating agency stated last week.

I believe the risk posed by this debt is systemic and could do more damage to the economy than the recent financial crisis. To understand the size of the risk, take a look at the numbers that Standard and Poor’s considers. The deficit in 2019 is expected by the CBO to be $1,200bn (€859bn, £754bn). Income tax revenues are expected to be about $2,000bn that year, so a permanent 60 per cent across-the-board tax increase would be required to balance the budget. Clearly this will not and should not happen. So how else can debt service payments be brought down as a share of GDP?

Inflation will do it. But how much? To bring the debt-to-GDP ratio down to the same level as at the end of 2008 would take a doubling of prices. That 100 per cent increase would make nominal GDP twice as high and thus cut the debt-to-GDP ratio in half, back to 41 from 82 per cent. A 100 per cent increase in the price level means about 10 per cent inflation for 10 years. But it would not be that smooth – probably more like the great inflation of the late 1960s and 1970s with boom followed by bust and recession every three or four years, and a successively higher inflation rate after each recession.

The fact that the Federal Reserve is now buying longer-term Treasuries in an effort to keep Treasury yields low adds credibility to this scary story, because it suggests that the debt will be monetized. That the Fed may have a difficult task reducing its own ballooning balance sheet to prevent inflation increases the risks considerably. And 100 per cent inflation would, of course, mean a 100 per cent depreciation of the dollar. Americans would have to pay $2.80 for a euro; the Japanese could buy a dollar for Y50; and gold would be $2,000 per ounce. This is not a forecast, because policy can change; rather it is an indication of how much systemic risk the government is now creating.

Why might Washington sleep through this wake-up call? You can already hear the excuses.

“We have an unprecedented financial crisis and we must run unprecedented deficits.“ While there is debate about whether a large deficit today provides economic stimulus, there is no economic theory or evidence that shows that deficits in five or 10 years will help to get us out of this recession. Such thinking is irresponsible. If you believe deficits are good in bad times, then the responsible policy is to try to balance the budget in good times. The CBO projects that the economy will be back to delivering on its potential growth by 2014. A responsible budget would lay out proposals for balancing the budget by then rather than aim for trillion-dollar deficits.

“But we will cut the deficit in half.” CBO analysts project that the deficit will be the same in 2019 as the administration estimates for 2010, a zero per cent cut.

“We inherited this mess.” The debt was 41 per cent of GDP at the end of 1988, President Ronald Reagan’s last year in office, the same as at the end of 2008, President George W. Bush’s last year in office. If one thinks policies from Reagan to Bush were mistakes does it make any sense to double down on those mistakes, as with the 80 per cent debt-to-GDP level projected when Mr Obama leaves office?

The time for such excuses is over. They paint a picture of a government that is not working, one that creates risks rather than reduces them. Good government should be a nonpartisan issue. I have written that government actions and interventions in the past several years caused, prolonged and worsened the financial crisis. The problem is that policy is getting worse not better. Top government officials, including the heads of the US Treasury, the Fed, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Securities and Exchange Commission are calling for the creation of a powerful systemic risk regulator to reign in systemic risk in the private sector. But their government is now the most serious source of systemic risk.

The good news is that it is not too late. There is time to wake up, to make a mid-course correction, to get back on track. Many blame the rating agencies for not telling us about systemic risks in the private sector that lead to this crisis. Let us not ignore them when they try to tell us about the risks in the government sector that will lead to the next one.

The writer, a professor of economics at Stanford and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, is the author of ‘Getting Off Track: How Government Actions and Interventions Caused, Prolonged, and Worsened the Financial Crisis’

(added on 5/30/2009): there is also a nice CNBC interview of John Taylor on the inflation worry: