Home » 2010 (Page 13)

Yearly Archives: 2010

Where to invest?

Investment strategist at BNP Paribas, ‘entertains’ you with some good ideas:

How recession in debt deleveraging cycle different?

We’re in a time of unusual economic uncertainties.

David Rosenberg thinks, in the following video discussion, that this recession is fundamentally different from post-war recessions. The difference is this severe recession is coupled within a secular cycle of credit contraction.

While others think the US is in a subdued period of economic growth. Once unemployment starts getting better, and household gradually improves their balance sheets, with huge corporate cash piled up waiting to be invested, it’s a matter time that American economy will be back on track.

A lively discussion – don’t miss this one:

Demographics and Wealth of Nations

Following my previous post, “India needs manufacturing“, in which future population growth trend was analyzed, today I post another analysis from WSJ’s David Wessel on the relationship between demographics and nation’s wealth. Before that, I would like to give some background.

China’s huge population was long thought to be a development burden for the country. High population density puts all kinds of resources under pressure – water, energy, environment, traffic, etc. And if you take a static view, more population simply leads to lower living standards (if you measure living standards simply by GDP per capita). Simple math shows despite the fact that China is the second largest economy in the world (with total GDP 1/3 of the US), China’s GDP per capita is only 1/10 of the United States, as its population is 3 1/2 times larger.

China’s population surge during the second half of the 20th century was largely man-made. After 1949, when China’s Communist Party established People’s Republic, there was a big fear that the US may invade mainland China, along with the defeated Nationalist Party. During the era of conventional warfare, the size of army mattered. Chairman Mao, China’s paramount first-generation leader, encouraged every Chinese family to have more children – three, four, or even more. Such policy rendered probably the sharpest population growth in China’s modern history.

China’s policymakers soon realized they made a huge mistake. The immediate concern was how to feed the rising population when China was still in total blockage under Western Sanction (like today’s North Korea). The deliberation at the highest level then manufactured China’s unique “One Child Policy” (OCP), now worldly famous – which went into effect since mid 1970s, and got really tough since early 1980s. In urban China, OCP is strictly enforced; in rural China, it is more relaxed, especially when the first baby happens to be a girl.

Now after more than 30 years, Chinese policymakers had another problem – The rapidly shrinking young labor force. Over the past 30 years, China’s huge labor reserve (or cheap labor) has contributed a great deal to her fast economic growth. Ironically, once the growth engine started, population turned out to be a growth dividend, not a burden. China’s huge population also attracted tremendous foreign investments – who would not want a bite in the largest domestic market in the world?

But the ‘young’ developing China is forecast to face ageing problem much sooner than most countries at its development stage. To replenish population, the fertility rate should stay at least 2. Any rate below 2 means declining population (this assumes birth rate and death rate are roughly the same, but if people live longer, this will generate a larger share of older population). For thirty years, China’s fertility rate has only been slightly above 1. OCP effectively controlled China’s population growth, but also put China onto a “fast lane” toward ageing society.

Let’s get to details: One-Child Policy started roughly around 1980, so the first cohort of young population (about 20 years old) entered labor force around year 2000, that’s when China suffered its first dent on labor force. It’s no coincidence that during the same time various reports surfaced that manufacturing firms in China’s east coast started to feel labor shortage, defying the popular image that China seemed to have unlimited labor supply. The shrinking labor supply will become more severe when the last large cohort of population born right before OCP exits the manufacturing. I assume this is going to happen from now to the next five years (2010-2015), when most of these workers reach their middle-age (35 to 40). With more working experiences and skills, especially, the migrant workers in this group will seek more stable income and better location with equal social benefits. This often means exits from coastal manufacturing.

China’s young labor force will continue to shrink until 20 years after the major policy reversal. The policy reversal now in effect is to allow qualified couples to have up to two children, if both husband and wife are the only child in their own families. Let’s assume these couples will have their children between 25 and 35 years old (or between year 2005 to 2015 for the first cohort). Only when their children grow old enough to join labor force, i.e, when they become abut 20 years old (or between 2025 and 2035), will China’s young labor force start to grow again. This simply means within roughly a 30-year range, from 2000 to 2030, China’s young labor force will continuously trend downward. For a country still at its early development stage, this forecast should sound high alert to policy makers.

If you want to know about the role of population in country’s growth and development, feel free to download my lecture notes on the population theory. Economist Magazine also has a terrific article, “Does Population Matter?”

Now without further adieu, I introduce you to David Wessel’s analysis on the “Demographics and Nation’s Wealth“. Pay special attention to the US’ future demographic trend, and what can we learn from it.

Demography is not destiny. In 1300, China was bigger than Europe and had the world’s most sophisticated technology. But China blew it. By 1850, its population was 65% larger than Europe’s, but—thanks to the Industrial Revolution—Europeans were far richer.

Yet demography does matter. “We never pay enough attention to demography because it’s so long term,” says Dominique Strauss-Kahn, head of the International Monetary Fund. So turn for a moment from angst about the disappointing pace of the economic recovery and daunting government budget deficits, and look over the horizon.

Over the next 40 years, Japan and Europe will see working-age populations shrink by 30 million and 37 million, respectively, according to United Nations projections. Birth rates are low and so many of their people are already elderly.

China’s working-age population will keep growing for 15 years or so, then turn down, the result of its one-child policy and the tendency of birth rates to fall as incomes rise. In 2050, the U.N. projects, China will have 100 million fewer workers than it does today. India’s population, in contrast, will grow by 300 million working-age persons over the next 40 years.

The U.S. is in between, benefiting from a higher birth rate and younger populations than Europe and Japan and more immigration. It is projected to add 35 million working-age persons by 2050.

So what?

History, as interpreted by modern economists pondering the mysteries of growth, teaches that more people lead to more ideas. And unlike land or oil, ideas can be used by more than one person simultaneously. Before countries began sharing ideas, the biggest had the most rapid technological progress. Now, trade, travel and the Internet speed new ideas around the globe ever-more rapidly. So the benefits are dispersed. Belgium is rich not because it is big or has invented a lot, but because it has the wherewithal to employ technology invented by others, notes Michael Kremer of Harvard University. Zaire is bigger, but lacks the wherewithal.

…

“China’s population is roughly equal to that of the U.S., Europe and Japan combined,” optimistic Stanford University economists Chad Jones and Paul Romer observed recently in an academic journal. “Over the next several decades, the continued economic development of China might plausibly double the number of researchers throughout the world pushing forward the technological frontier. What effect will this have on incomes in countries that share ideas with China in the long run?” Somewhere between a lot and really a lot, they say. In fact, they say that even if the U.S. had to bear all the costs of mitigating the added carbon emitted by a rapidly developing China, ideas generated by the Chinese would boost U.S. per capita income enough to more than compensate.

…

For China, the challenge is to build social structures and retirement schemes to sustain a growing cadre of old folks that, unlike previous generations, won’t be able to rely so much on its children for support. Today, 1.4% of Chinese are over age 80; in 2050, 7.2% will be, the U.N. projects.

…

And the U.S.? For all today’s gloom, it may be in the sweet spot. A growing population, an openness to ambitious immigrants and trade (if not disrupted by xenophobic politics) and strong productivity growth (if sustained) could lift living standards and bring faster growth, which would reduce big government budget deficits far easier for the U.S. than for slower growing Europe and Japan.

The Rise of Permabears

The talk of deflation itself may serve as a self-fulfilling prophecy. NYT reports the pessimism toward the US economy now became "fashionable" among mainstream economists and investors – call it "the rise of permabears".

We may all lose our spectacles.

Why NBER hasn’t declared “recession is over”

David Rosenberg explains why:

There are two other critical factors preventing NBER from declaring the all-clear signal.

First, despite the dramatic rebound in the equity market in 2009, personal income fell in 49 of the 52 U.S. cities of a million population or more. The three cities that saw an increase were closely tied to the federal government (like Washington D.C.). Indeed, government pay managed to rise 2.6% last year while all the suckers that work in the private sector posted a 6% wage decline. How this doesn’t breed dissent is a legitimate question.

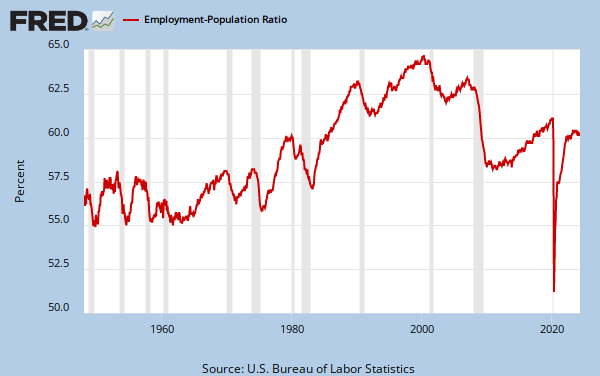

Second (…) is the rapid decline in the employment-to-population ratio. This is a far more informative measure regarding labour market performance than the traditional unemployment rate, especially at a time when discouraged workers are withdrawing from the labour force at such an alarming clip.

The employment rate has declined now for three months in a row, back to where it was at the start of the year, and smartalecks who see this recovery as anything but disturbing don’t realize that this employment rate, at 58.4%, is down from 64.0% at the 2007 high. This was the largest drop in the post-war era and what it means is that the economy is 12 million jobs shy of being at full employment.

Instead of declaring an outright war on unemployment, we instead have a government bent on measures to boost spending on cars and homes that nobody really wants since, at the margin, all people want to do is boost their once-depleted savings rates and get out of debt; or at least a half dozen housing plans to help distressed mortgage borrowers. Or infrastructure spending that so far seems to have helped line the pockets of public sector union officials with no obvious payback in terms of job creation. At least FDR paid people to work, even if it meant skyscrapers, bridges, monuments and national parks. They didn’t get paid do sit idle for 99 weeks so they can then drop out of the labour force and into oblivion (almost 45% of the unemployed have been so for more than 26 weeks — in no other recession in the past six decades did this share ever cross above 26%).

Almost half of the ranks of the unemployed have been looking for a job fruitlessly for at least six months. Let’s get these people re-engaged in the labour market, get them re-tooled and retrained for the skill set that businesses need now and in the future. Give these folks a shovel from 8 to 12 and engineering courses from 1 to 5 in return for their jobless insurance check. It’s time to get creative and aggressive with minimal cost to the taxpayer. If we can win this fight against unemployment, it’s amazing what other positive things will fall into place, from housing demand to government revenues to consumer credit quality.

Hong Kong – China’s currency lab

When to liberalize Chinese currency, Yuan or RMB? How to make Yuan more internationally influential? Hong Kong is being used by Chinese government as their forefront currency experiment lab. Reports WSJ:

![[HKVIEW]](https://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BE974_HKVIEW_NS_20100801171253.gif)

A burst of activity is under way here in the city that might be called China’s in-house research-and-development center for currency liberalization.

It’s on a tiny scale by normal standards of the $3 trillion-a-day market for foreign exchange. But in Hong Kong, banks are for the first time starting to lend yuan to one another outside mainland China and offering hedging services that weren’t available before. The result, say bankers, is reminiscent of the eurodollar market in the early 1960s, when extensive dealings in the greenback outside U.S. borders first took off.

The catalyst for this activity was an agreement signed June 19 between monetary authorities in mainland China and Hong Kong removing certain limits on usage of China’s yuan within Hong Kong. In the past, businesses were mostly confined to opening yuan accounts for trade-settlement purposes; now, accounts can be opened for any purpose. Businesses and individuals alike now can transfer yuan freely between accounts. Banks also can help businesses convert yuan without restriction.

…

With the latest liberalization move, banks in Hong Kong are now freer than ever to take all that yuan and put it to work. Some speak of linking the interest rate paid on yuan deposits to the direction of the euro or gold prices. Frances Cheung, senior strategist at Crédit Agricole Corporate & Investment Bank, foresees a market for yuan interest-rate swaps as interbank lending in the currency gains momentum.

…

Meanwhile, more and more yuan pour into Hong Kong. Monthly trade between Hong Kong and mainland China settled in yuan jumped tenfold from January to June to 13.24 billion yuan, or nearly $2 billion, and it’s set to rise more quickly since a pilot program allowing yuan settlement expanded to cover more of China in June.

Qu Hongbin, chief China economist at HSBC in Hong Kong, believes we are seeing just the tip of the iceberg. The anomaly, he says, is the fact that China conducts virtually all its trade in dollars, euros or yen. Historically, he says, “we’ve never seen a case where the world’s largest exporter uses other people’s currency for their trading.”

Hiring Mismatch

The Journal yesterday had a fantastic article on why some firms can't fill their positions when the unemployment rate is around 10%. Sounds ironic, isn't it?

All comes down to mismatch of skills. Also think about this in historical perspective: the long declining of US manufacturing…smart kids flooded to finance and the Wall Street; now with Wall Street in shamble, some jobs are permanently lost, and they are not going to come back.

The hiring for high-skilled and low-skilled workers are rising, while demand for middle-skilled are decreasing:

Unleash America’s Dynamism

Ed Phelps, Nobel prize winner in economics in 2006, put out his plan to revitalize American economy (source: NYT):

The Economy Needs a Bit of Ingenuity

By EDMUND S. PHELPS

THE steps being taken by government officials to help the economy are based on a faulty premise. The diagnosis is that the economy is “constrained” by a deficiency of aggregate demand, the total demand for American goods and services. The officials’ prescription is to stimulate that demand, for as long as it takes, to facilitate the recovery of an otherwise undamaged economy — as if the task were to help an uninjured skater get up after a bad fall.

The prescription will fail because the diagnosis is wrong. There are no symptoms of deficient demand, like deflation, and no signs of anything like a huge liquidity shortage that could cause a deficiency. Rather, our economy is damaged by deep structural faults that no stimulus package will address — our skater has broken some bones and needs real attention.

The good news is that some of the damage done in the past decade will heal. The pessimism that broke out in 2009 is dissipating. The oversupply of houses and office space, which is depressing construction, will wear off. Banks and households are saving quickly enough to retire most of their excessive debt within a decade.

But other problems are not self-healing. In established businesses, short-termism has become rampant. Executives avoid farsighted projects, no matter how promising, out of a concern that lower short-term profits will cause share prices to drop. Mutual fund managers threaten to dump shares of companies that miss quarterly earnings targets. Timid and complacent, our big companies are showing the same tendencies that turned traditional utilities into dinosaurs.

Meanwhile, many of the factors that have long driven American innovation have dried up. Droves of investors, disappointed by their returns, have abandoned the venture capital firms of Silicon Valley. At pharmaceutical companies, computer-driven research is making fewer discoveries than intuitive chemists once did. We cannot simply assume that, when the recession ends, American dynamism will snap back in place.

Many pin their hopes for reviving the economy on gains in worker productivity. But such workplace advances often destroy more jobs than they create. That happened in the Great Depression, when increased worker productivity allowed companies and the economy to expand without creating new jobs.

The decline in American dynamism is not the only problem. It has been accompanied by a decline of what I call inclusion. Not only were low-wage workers largely cut out of the economic gains of the 1990s and 2000s — much of the middle class was, too. In part, this is because the emerging economies around the globe have ended our competitive advantage in manufacturing, and jobs have fled. We can’t compete in those industries any more, and our business sector has not yet found new advantages.

The worst effect of focusing on supposedly deficient demand is that it lulls us into failing to “think structural” in dealing with long-term problems. To achieve a full recovery, we have to understand the framework on which our broad prosperity has always been based.

First, high employment depends on a high level of investment activity — business expenditures on tangibles like offices and equipment, and also training for new or existing employees, and development of new products.

Sustained business investment, in turn, rests on innovation. Business cannot wait for discoveries in science or the rare successes in state-run labs. Without cutting-edge products and business methods, rates of return on a great many investments will sag. Furthermore, innovation creates jobs across the economy, for entrepreneurs, marketers and buyers. State-led technology projects do not.

High business investment also depends on companies having confidence in the future. A company might be afraid to invest in research or product lines if it fears the rest of the economy is not doing the same — or if it fears the government might become hostile to its goals. During the Depression, John Maynard Keynes warned President Franklin D. Roosevelt not to damage business confidence with anti-profit rhetoric — to treat titans of business “not as wolves or tigers, but as domestic animals by nature.”

What, then, is to be done? One reform would be to create a First National Bank of Innovation — a state-sponsored network of merchant banks that invest in and lend to innovative projects. Another would be to improve corporate governance by tying executives’ compensation to long-term performance rather than one-year profits, and by linking fund managers’ pay to skill in picking stocks, not in marketing their funds. Exempting start-ups from corporate income tax for a time would also help.

We also need a program of tax credits for companies for employing low-wage workers. That may seem counterintuitive at a time when the Obama administration is pressing education and high-paying jobs, but we need to create jobs at all levels. Early last year, Singapore began giving such credits — worth several billion dollars — and staved off a recession. Unemployment there is around 3 percent.

A revamp of the economy for greater dynamism and inclusion is essential for prosperity and growth. Rather than continuing to argue over solutions to a problem we do not have — low demand — the country needs to focus on fixing the structural problems that, unresolved, will stymie the economy over the long haul.

![[Capital]](https://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/NA-BH438_Capita_NS_20100811192813.gif)

![[HIRE_jmp]](https://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AW649A_HIRE__NS_20100808183616.gif)

![[HIRE_p1]](https://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AW648_HIRE_p_NS_20100808185217.gif)