Home » Uncategorized (Page 17)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Economic recovery is under way

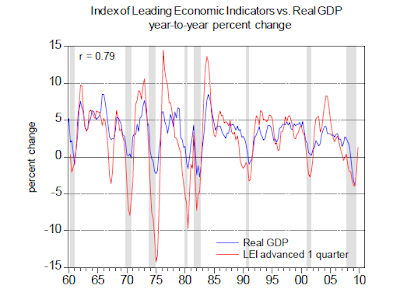

Equity market may be overpriced, and is due for a correction in the near term. But the big-picture direction for the economy is on the way up. This trend is very clear if you look at the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Indicator, LEI.

LEI and GDP growth are highly correlated, with correlation ratio near 80%.

Lessons from ‘the lost decade’

Source: WSJ

Much of the financial news this month has revolved around the one-year anniversary of the Panic of 2008 — the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the takeover of Merrill Lynch, the government’s bailout of Wall Street.

But there’s another anniversary for investors. It is 10 years this weekend since the publication of “Dow 36,000: The New Strategy for Profiting From the Coming Rise in the Stock Market,” a popular seller that became the poster child of 1990s stock-market hubris.

Authors James K. Glassman and Kevin A. Hassett weren’t quite the Dan Browns of their day, but in their book they nonetheless claimed to have discovered a virtual secret code buried within the stock market.

In a nutshell, they argued that, even in that period of wildly “irrational exuberance,” shares were massively undervalued. Their reading of history revealed that shares were far less risky over time than was widely assumed. As a result, they concluded that the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which at the time stood at 10300 or so, was really worth more than three times as much.

It’s easy to mock that brash forecast now. But few were laughing at the time. On the contrary, although only some on Wall Street were willing to take the arguments to these ridiculous extremes, many shared their underlying assumptions.

Back then, the only people subject to sustained derision on Wall Street were those who dissented. Anyone who warned that shares might disappoint was ignored. The few predicting a crash — let alone two — were considered cranks. (For the record: The Dow, which continues to enjoy a remarkable post-crash rally, rose another 2.2% last week; it’s up 50% since March. But it’s still below where it stood in September 1999.)

Beyond a sorry contemplation of the past 10 years, what does this anniversary offer investors? What have we learned from the last decade? And where do we go from here?

Here are seven lessons of a lost decade:

1 Don’t forget dividends. In the 1990s bubble, investors figured they were going to make all their money on capital gains. That’s a reason they were willing to buy shares paying out little or nothing.

Reality: Dividends have been investors’ life raft since. The Dow has fallen about 7% since the book came out. But when you include reinvested dividends, investors in the market are about even over that period.

2 Watch out for inflation. Price increases have been modest in the past decade, but during that period the dollar has still lost about 23% of its purchasing power.

So investors in the market have really gone backward. Ignoring inflation is a mistake too many are making again now as they keep all their money in bank accounts paying little or nothing. What matters isn’t just your nominal or headline return. It’s your return — after inflation.

3 Don’t overestimate long-term stock-market returns. It’s remarkable to replay all those foolish, over-optimistic assumptions you used to hear everywhere about the stock market — “Wall Street goes up by around 8% to 10% a year,” “shares will earn 7% above inflation over the long term” and so on.

What’s the truth? A global study conducted a few years ago by the London Business School suggested the average long-term return may have only been about 5% over inflation, rather than 7% or more.

That may not sound like a big difference, but over time it’s huge. It cuts your likely profits by a third over a single decade. And it means you run a much bigger risk that you will lose money over long periods.

4 Volatility matters. Be honest: Did you scale back your investments in March, when the Dow was below 7000? How about in 2002, when markets were in free-fall? Many people did. And no, it wasn’t just folly. On both occasions, share prices were roughly halved from their peak. Many people simply couldn’t afford the risk that prices could fall another 50%. Investors felt they were playing Russian roulette.

5 Price matters (my comment: or entry point matters). The biggest problem in 1999 was simply that over the previous 17 years the stock market had already gone up tenfold — from around Dow 1000 in 1982 to 10000 in 1999. Shares on average were heavily overvalued. No wonder they have been a poor investment since.

6 Don’t hurry. Too many investors rushed to “get on board” 10 years ago, and paid the price. Wall Street encourages the habit: Fund managers and brokers like to use the grossly misleading phrase “let’s put your money to work” for this reason, even though anyone who “put their money to work” in 1999 lost money. Memo to potential investors: There is never a hurry, never a reason to rush.

7 Don’t forget your lifeboats! The biggest problem with the Titanic wasn’t that the captain was expecting a safe journey when he set sail. It was that the management was expecting a safe journey when it ordered so few lifeboats. Hope for the best — but plan for the worst. This is the reason for including nonequities in a portfolio, including inflation-protected government bonds and other assets.

Where are we now? What can we expect for the future?

The good news is that markets are no longer anywhere near as overvalued as they were 10 (or two) years ago. Global markets, which hit a peak of about 25 times forecast earnings in early 2000, are now a more reasonable 16 times. The global dividend yield has doubled to 2.5%. The bad news is shares aren’t cheap either. Skeptical value managers — a rare but valuable breed — argue shares may be 10% or 20% above fair value.

That’s an argument for holding a good amount of shares — and plenty of dry powder.

Rosenberg: Too much risk in equity market

David Rosenberg, former chief US economist at Merrill Lynch, thinks the current rally went too far and now the risk of near-term correction outweighs a continuous rally. (highlights and comments are mine)

Never before has the S&P 500 rallied 60% from a low in such a short time frame as six months. And never before have we seen the S&P 500 rally 60% over an interval in which there were 2.5 million job losses. What is normal is that we see more than two million jobs being created during a rally as large as this.

In fact, what is normal is for the market to rally 20% from the trough to the time the recession ends. By the time we are up 60%, the economy is typically well into the third year of recovery; we are not usually engaged in a debate as to what month the recession ended. In other words, we are witnessing a market event that is outside the distribution curve.

While some pundits will boil it down to abundant liquidity, a term they can seldom adequately defined. If it’s a case of an endless stream of cheap money, we are reminded of Japan where rates were microscopic for years and the Nikkei certainly did enjoy no fewer than four 50% rallies and over 420,000 rally points in a market that is still more than 70% lower today than it was two decades ago. Liquidity and technicals can certainly touch off whippy tradable rallies, but they don’t take you all the way to a sustainable bull market. Only positive economic and balance sheet fundamentals can do that. (comments: but if liquidity and market rally can bring back business confidence, it's not without possibility that business investment will catch up later too.)

Another way to look at the situation is that when you hear and read about “liquidity” driving the market, it is usually a catch-all phrase for “we have no clue” but it sounds good. When we don’t have a reasonable explanation for what is driving prices our strategy is to watch from the sidelines and express whatever positive views we have in the credit market and our other income and hedge fund strategies.

As for valuation, well let’s consider that from our lens, the S&P 500 is now priced for $83 in operating EPS (we come to that conclusion by backing out the earnings yield that would match the current inflation-adjusted Baa corporate bond yield). That would be nearly double from the most recent four-quarter trend. Not only that, but the top-down estimates on operating EPS, for 2009 are $48.00 for 2009; $52.60 for 2010; $62.50 for 2011; and $81.00 for 2012. The bottom-up consensus forecasts only go to 2010 and even for this usually bullish bunch, operating EPS is seen at $73.00 for 2010, which means that $83.00 is likely a 2011 story. Either way, the market is basically discounting an earnings stream that even the consensus does not see for another two to three years. In other words, this is more than just a fully priced market at this point.

It is, in fact, deeply overvalued at this juncture. Imagine that six months after the depressed lows we have a situation where:

• The trailing price-earnings ratio on operating EPS is 26.5x. At the October 2007 highs, it was 18.8x. In addition, when the S&P 500 is trading north of a 26x P/E multiple on trailing operating earnings, history shows that at these high valuation levels, the market declines in the coming year 60% of the time.

• The trailing price-earnings ratio on reported EPS is 184.2x. At the October 2007 highs, it was 23.4x. In fact, just prior to the October 1987 crash, the P/E ratio was 20.3x (not intended to scare anyone).

• The price-to-dividend ratio is 53x, where it was at the 2007 highs. Again, the market is trading as it if were at a peak for the cycle, not any longer near a trough. Once again, and we don’t intend to sound alarmist, the price-to-dividend ratio just prior to the 1987 crash was 12x, and at the time, the S&P 500 was viewed in many circles to be at an extended extreme.

Bullish analysts like to dismiss the actual earnings because they are “depressed” and include too many writeoffs, which of course will never occur again. Fine, on one-year forward (operating) earning estimates, the P/E ratio is now 15.7x, the highest it has been in nearly five years. At the peak of the S&P 500 in the last cycle — October 2007 — the forward P/E was 14.3x, and the highest it ever got in the last cycle was 15.4x. So hello? In just six short months, we have managed to take the multiple above the peak of the last cycle when the economic expansion was five years old, not five weeks old (and we may be a tad charitable on that assessment). As an aside, the forward multiple on the eve of the 1987 stock market collapse was 14x and one of the explanations for the steep correction was that equities were so overvalued and overbought that it was vulnerable to any shock (in that case, it came out of the U.S. dollar market). It certainly was not the economy because that sharp 30% slide took place even with an economy that was humming along at a 4.5% clip.

In other words, valuation may not be the best timing device, but it still matters. If the S&P 500 was in a 700-750 range, de facto pricing in zero to 1% real GDP growth, we would certainly be interested in boosting our allocations towards equities. But at 1,060 and over 4.0% GDP growth effectively being discounted, we will be spectators as opposed to participants, understanding that the key to success is to NOT buy at the peaks. So the strategy is to sit on the sidelines, be selective in our equity choices, and wait for the correction to come or for the fundamentals to catch up with this overvalued, overbought, overextended market. Remember, the reason why the tortoise won the race was because the hare got tired.

One more thing, when people look back at this period, they are very likely going to ask themselves why it was that they never paid attention to the volume data, which, like the bond and money market, never confirmed the veracity of this very flashy bear market rally. We reiterate, Japan enjoyed four of these 50% power surges in the context of a market that is still down over 70% from its highs of two decades ago. So remember, rallies in a bear market are to be rented; never owned. For those that never took the opportunity to get out at the lows today have this glorious chance to do so at much better prices, but the question is whether greed has overtaken their long-term resolve, especially now that Gordon Gekko is making a return to the big screen.

Is salaried doctor the solution?

There gotta be some alternatives to what Obama is proposing.

Incentives, incentives, incentives.

Too hard to break China’s savings habit

Why do Chinese save so much?

BBC reports

Becker: How much should we care about budget deficit

Insights from Nobel winning Gary Becker, professor of economics at University of Chicago:

To the extent that the source of the rise in a deficit is increased government spending, then whether that rise is justified depends on how socially valuable are these government expenditures. By that I mean the social rates of return on these expenditures, such as longer lives for the elderly, relative to the interest cost of raising the required funds, and relative to the returns on other investments in the economy. Much of the increased government spending in different countries during this recession went to help out banks that were in danger of going under. While numerous mistakes were made that will be argued about for a long time, such spending on the whole was necessary in order to limit the financial crisis that had developed.

Other parts of the increase in spending in most countries are far more dubious and may even have harmed their economies. I include in that most of the $800 billion Obama stimulus package, much of which is still not spent even though the brunt of the recession is over This package was promoted as a way to fight the recession, but mainly it is an attempt to re-engineer the economy in the directions of larger government favored by many liberal Democrats. I believe much of this reengineering will hurt the functioning of the economy, and of course at the same time will add to the debt burden.

A very small example was the cash for clunkers program in the US that ended a short time ago. The 19th century French essayist Frederic Bastiat discussed facetiously the gain to an economy when a boy breaks the windows of a shopkeeper since that creates work for the glazier to repair them, and the glazier then spends his additional income on food and other consumer goods. The moral of that story is to hire boys to go around breaking windows! The clunkers program was hardly any better than that (see our discussion of the clunkers program on August 24th).

Deficits also arise automatically during recessions because tax revenues fall as the growth in aggregate incomes slows down, and even becomes negative, as it did during this recession. This automatic effect on deficits during recessions from falling tax revenues is supposed to be balanced by automatic surpluses during prosperity times as tax revenues grow because income are expanding faster. Unfortunately, the period prior to the recession also had budget deficits, even though incomes grew quite fast, because Congress and President Bush pushed for greatly expanded spending.

To turn to the second question, will financing the debt become a serious obstacle to rapid US growth as the current and projected sizable US deficits increase the ratio of government debt to American GDP? That depends on four critical variables: the size of the debt/GDP ratio, the level of interest rates, tax rates, and the rate of productivity growth in the American economy. Suppose the debt held by the public-which excludes government debt held by other government agencies- reaches 100% of present or near term GDP, which is not unlikely.

The burden on the government budget that this imposes depends on the interest rates on the debt. At an average interest rate of 5%, that means 5% of GDP would go to servicing the debt, which is a little less than 20% of total federal government spending. This might be manageable but it is not trivial. On the other hand, if average interest rates were only 3%, servicing costs would be far more tolerable. In fact, the US has been paying about 3% on its debt, so even a considerable increase of the debt to 100% of GDP would still be manageable. But if the Fed starts raising real interest rates to head off the inflation potential in the $800 billion of excess reserves, the debt burden could become a major problem. Another factor is the savings rates coming from the Asian countries, like China. If their savings decline sharply, that too would raise world interest rates and increase the debt burden for all countries.

Rapid productivity growth and an improved tax structure could save the situation because the expansion of GDP caused by such growth and better taxes lower the ratio of the debt to GDP, and makes financing the debt easier. To maintain rapid productivity growth requires that an economy provide powerful incentives to invest in physical and human capital and R&D. It also requires that Congress and other legislatures do not start growing government spending as GDP grows rapidly. But members of Congress and other legislatures are tempted to use much of the growing tax revenue on their pet projects.

One important determinant of the incentives to invest is the tax rates on the rewards of investments in new knowledge and capital. Rich people should pay a larger share of the tax burden, and they do. However, if the emphasis changes from encouraging investments to redistribution, the poor as well as the rich will suffer. Probably the poor will suffer more since the rich can more their capital and themselves to the many low tax jurisdictions in the world.

![[Dusan Petricic]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-EM413_sun092_DV_20090918192858.jpg)

![[what were they thinking]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/SJ-AD868_LEDE_C_NS_20090918180048.gif)