Home » Uncategorized (Page 19)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Treasuries or gold?

Which is a better investment, under different scenarios? WSJ analyzes:

Is the outlook for the world economy dark enough for gold to continue to glitter?

Remarkably, the gold price has appreciated 12% since April, a period during which financial-meltdown fears appear to have receded and investors have rushed back into riskier assets. Gold's resilience suggests continuing demand for an asset that could outperform in worst-case scenarios.

But not every difficult economic outcome is the same. That is something investors need to remember as they decide whether gold — rather than Treasurys — really is the best disaster hedge.

Treasurys start with several advantages. They produce an income stream, whereas gold doesn't. And, although Treasurys would be hit if there is a strong economic rebound with low inflation, gold would likely be hammered.

Next, Treasurys actually did better than gold in the fear-drenched period at the end of last year. The Merrill Lynch price index for the 10-year Treasury jumped 11.6% from September through the end of 2008. The Comex gold price was up 6.6% over the same period, and it sold off sharply in the middle of the meltdown. That last fact suggests gold benefits when markets are functioning — like now — but the metal, like other assets, can fall when markets close down.

In other words, Treasurys could trump gold in a Japan-like environment, where deflation pushes up real yields but isn't high enough to cause serious stress on the financial system and the wider economy.

But gold has a big friend in Western central banks, especially the Federal Reserve, which is still printing enormous amounts of dollars to support key markets. This makes the inflation outlook uncertain, helping gold and hurting currencies like the dollar.

The printing looks set to continue. Ominously, this weekend, the G-20 said central-bank liquidity support "will need to remain in place for some time."

One area where that support could stay in place for a long time is for the U.S. housing market. Right now, there is almost no private-sector demand for nonconforming residential mortgages, reflected in the fact that the U.S. government has effectively or explicitly guaranteed as much as 85% of all mortgages originated this year, according to Inside Mortgage Finance. In turn, the Fed is buying nearly 80% of government-backed mortgages packaged in securities. If it pulls back, house prices could resume their slide, triggering more foreclosures and losses for banks.

Finally, soaring fiscal deficits favor gold. The IMF expects G-7 countries to show a combined fiscal deficit equivalent to 10.36% of GDP this year, more than double the level following the 1990-91 recession. True, it is impossible to time a fiscal Armageddon bet. The yen has stayed strong even as Japanese government borrowing has exploded over the past 20 years.

But government finances are now deteriorating in most developed countries.

For pessimists, if we're in for a Japanese-style deflationary bust, buy Treasurys. For other disaster scenarios, go for gold.

How big is China’s Green Energy

Source: BoFIT

Although the relative share of electrical power generated by renewable energy systems is still small in China, the country has made remarkable progress in adopting new approaches in recent years. The amount of wind-generated electricity quadrupled between 2006 and 2008, and today China has the world’s fourth largest wind power generation capacity after the US, Germany and Spain. Large dam projects have also helped double hydro-power generation since 2002. Solar power use has increased dramatically along with incentives such as direct subsidies to e.g. building owners who install solar panels on their buildings. Moreover, China is planning to construct one of the world’s largest solar fields in Inner Mongolia.

The introduction of renewable power technologies has not been without difficulties. Despite state support for construction of wind farms, companies that operate the electricity grid have little incentive bring wind farms, which are often located in remote areas, onto the grid. By some estimates, as much as 20 % of wind power currently generated in China is still off-grid and capacity utilization of wind farms has been lower than expected. There have also been problems with hydro-power projects as China struggles with droughts and uncertainty over the long-term environmental impacts of huge dams.

Despite the rapid rise of sustainable energy systems, they still generate a small share of China’s total electricity (see chart). Hydro-power accounts for 16 % of electrical power generation, and wind just 0.4 %. Coal, in contrast is the basis of more that 80 % of China’s power generation. China’s goal is to raise the share of electricity generated by renewable systems to over 20 % by 2020.

China is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide. A substantial amount of these emissions are generated by coal-burning power plants. China’s future energy production will continue to rely heavily on coal-fired power plants and China has not committed to Kyoto treaty emission targets. International climate talks will continue in December at the Climate Summit in Copenhagen.

China’s CO2 emissions should fall slightly as the country makes gains in energy efficiency and its worst-polluting coal-fired power plants are shut down. A target of the cur-rent five-year plan (2006–2010) is to reduce energy consumption by 20 % relative to China’s per capita GDP. Although progress towards this decrease has been achieved, it appears unlikely that the target will be met.

Although the state has passed an energy saving law and launched a raft of energy-saving programs, heavy regulation of electricity prices erodes the incentive to be energy efficient. Moreover, there has not been political enthusiasm for deregulation of energy prices.

China is trying very hard to diversify away from US dollar

There is not much China can do, but purchasing IMF notes is a good away to increase its influence on international monetary policy.

The Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Mr. Dominique Strauss-Kahn, and the Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China, Mr. Yi Gang, have signed an agreement under which the People’s Bank of China would purchase up to SDR 32 billion (around US$50 billion) in IMF notes.

The note purchase agreement is the first in the history of the Fund, and follows the endorsement by the Executive Board on July 1, 2009 of the framework for issuing notes to the official sector. The Chinese authorities had expressed their intention to invest up to US$50 billion in IMF notes in June (see Press Releases No. 09/204 and No. 09/248).

The agreement offers China a safe investment instrument. It will also boost the Fund’s capacity to help its membership — particularly the developing and emerging market countries — weather the global financial crisis, and facilitate an early recovery of the global economy.

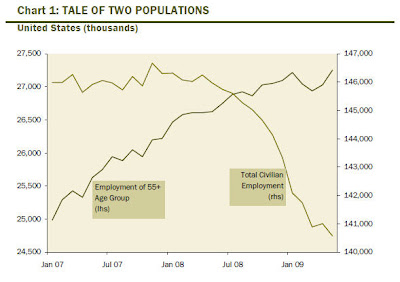

Shades of gray in employment

The unemployment rate is near 10%. Every age group is seeing decline of employment except for the age group that is above 55. What happened? This WSJ piece explains — It's not merely demographic change.

The Who famously sang they hoped they'd die before they got old. Clearly, they didn't want a proper job.

So far in this recession, 6.6 million jobs have been lost on a seasonally adjusted basis. That wipes out six of 10 jobs created in the last, unusually jobless, economic upswing. Every age group has lost jobs.

Except, that is, the cohort aged 55 and over, which has gained nearly one million positions. What's more, over-55s accounted for two-thirds of net jobs created in the upswing.

This has less to do with gray flair and more with a statistical wrinkle. The first of the postwar baby boomers hit official retirement age in 2011. That demographic bulge has been rolling through the age structure — in and out of the workplace — through this decade. According to Census Bureau estimates, the overall population age 55 to 64 grew by 9.4 million between July 2001 and July 2008. That isn't dissimilar to the roughly eight million increase in the ranks of employed over-55s between November 2001 and now.

But the figures point to more than just a demographic change. Over the same time period, the proportion of over-55s in employment rose five percentage points, possibly reflecting a need to re-enter the job market after the bursting of a tech bubble and a housing bubble damaged their net worth.

Meanwhile, labor participation fell for every other age group. For those age 16 to 24, for example, the rate fell almost 10 percentage points, to under half, even as that population group expanded. A graying work force focusing on rebuilding its nest egg while the young struggle for entry doesn't bode well for an economy dependent on sprightly consumers.

David Rosenberg also has a wonderful graph on this:

Why individual investors sit tight on their 401(k)s?

Part of it is individual's strong belief of the theory that stocks always outperform other assets in the long run; part of it is simple inertia (source: WSJ):

There are bears. There are bulls. And there are sitting bulls.

These are the legions of 401(k) investors who don't merely buy and hold; they buy, hold and sit stock-still. Even as the U.S. stock market fell 55% between October 2007 and March 2009, these people barely budged. Among the more than three million 401(k) participants served by Vanguard Group, 17% were 100% in stocks in 2007; at year-end 2008, 16% still were. Of the 11.2 million participants served by

Fidelity Investments, 15% still have every penny in their 401(k) invested in stocks, including 14% of those between the ages of 60 and 64.

The sitting bulls present a problem for hedge-fund managers and other professional investors who have argued that all it would take to shake individual investors' grip on stocks was a good old-fashioned bear market.

To be sure, the share of U.S. households that own stocks in any account has fallen from 53% in 2001 to around 45% in 2008, according to the Investment Company Institute and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. Since 2007, 401(k) investors at both Fidelity and Vanguard have lowered the rate of new contributions they are putting into stocks.

But those trends hardly constitute a stampede. At Vanguard, says Stephen Utkus of the Vanguard Center for Retirement Research, only 16% of 401(k) investors made any trades in 2008, barely up from 15% in 2007 and down from 20% in 2004. That includes rebalancing across funds to restore an asset mix to target levels.

"It is kind of striking," Mr. Utkus says. "We had the most drastic market decline since the Depression, we nearly had a total collapse of the global financial system, and all that caused most people not to do much at all."

After the Great Crash of 1929, individual investors abandoned the stock market for a generation. What keeps today's sitting bulls from running off?

First, these people are largely doing what they have been told, by researchers who have argued that stocks are risk-free in the long run, by mutual-fund companies that earn higher fees on stock funds and by stock-market advocates in the financial media.

Another factor is what Mr. Utkus calls the "contribution effect." For workers who are young, newly hired or lower-paid, falling market values are counteracted by the new cash pumped in with each payroll contribution. More than one-third of Vanguard's 401(k) investors didn't lose money in 2008, while another 10th lost 10% or less. These people were barely scathed by the stock-market crash.

Furthermore, 401(k) contributions are automatic and withdrawals are often decades in the future, reducing the apparent need for action today. Sir Isaac Newton's first law of motion might be reapplied to 401(k) investing: An investor at rest tends to stay at rest, even when acted upon by an unbalanced force.

This bovine behavior is driven partly by a very human need to simplify decisions that feel complex. Forced to choose how much money they want to put into stocks, many 401(k) investors don't treat it as a decision about how much risk they wish to take. Instead, they look for obvious rules of thumb. If you like stocks, why not put 100% of your money into them? If you don't, then why not set a zero allocation to stocks? And once you pick a nice round number, why change it?

Accounting professor Shlomo Benartzi of UCLA studied a large sample of investors who filled out a risk-tolerance questionnaire for a major 401(k) provider. Only 7% described themselves as aggressive; yet 33% invest as if they are, putting 80% to 100% of their 401(k) into stocks.

So inertia is often a state of mind, rather than a deliberate choice. It worked well in the 1980s and 1990s, and again over the past six months as the market partially rebounded from its collapse. For the past decade as a whole, it hasn't worked well. So investors should be patient, but not catatonic; they should rebalance annually to sell some of what has gone up and buy some of what has gone down.

If stocks are halved again, or we get another decade of poor returns, the sitting bulls might finally get up and leave the field. But nothing short of that seems likely to make them budge. Bears can maul most livestock, but they are no match for sitting bulls.

Subprime loan goes to India, a new bubble in microfinance

From WSJ:

A Global Surge in Tiny Loans Spurs Credit Bubble in a Slum

RAMANAGARAM, India — A credit crisis is brewing in "microfinance," the business of making the tiniest loans in the world.

Microlending fights poverty by helping poor people finance small businesses — snack stalls, fruit trees, milk-producing buffaloes — in slums and other places where it's tough to get a normal loan. But what began as a social experiment to aid the world's poorest has also shown it can turn a profit.

That has attracted private-equity funds and other foreign investors, who've poured billions of dollars over the past few years into microfinance world-wide.

The result: Today in India, some poor neighborhoods are being "carpet-bombed" with loans, says Rajalaxmi Kamath, a researcher at the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore who studies the issue. In India, microloans outstanding grew 72% in the year ended March 31, 2008, totaling $1.24 billion, according to Sa-Dhan, an industry association in New Delhi.

"We fear a bubble," says Jacques Grivel of the Luxembourg-based Finethic, a $100 million investment fund that focuses on Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia, though it has no exposure to India. "Too much money is chasing too few good candidates."

Here in Ramanagaram, a silk-making city in southern India, Zahreen Taj noticed the change. Suddenly, in the shantytown where she lives, lots of people wanted to loan her money. She borrowed $125 to invest in her husband's vegetable cart. Then she borrowed more.

"I took from one bank to pay the previous one. And I did it again," says Ms. Taj, 46 years old. In four years, she took a total of four loans from two microlenders in progressively larger amounts — two for $209, another for $293, and then $356.

At the height of her borrowing binge, she says, she bought a television set. The arrival of microfinance "increased our desires for things we didn't have," Ms. Taj says. "We all have dreams."

Today her house is bare except for a floor mat and a pile of kitchen utensils. By selling her TV, appliances and jewelry, she cut her debt to $94. That's equal to about a fourth of her annual income.

Around Ramanagaram, the silk-making city where Ms. Taj lives, the debt overload is stirring up social tension. Many borrowers complain that the loans' effective interest rates — which can vary from 24% to 39% annually — fuel a cycle of indebtedness.

In July, town authorities asked India's central bank to either cap those rates or revoke lenders' licenses. "Otherwise, the present situation may lead to a law-and-order problem in the district," wrote K.G. Jagdeesh, deputy commissioner for the city of Ramanagaram, in a letter to the central bank.

Alpana Killawala, a spokeswoman for the Reserve Bank of India, said in an email that the central bank doesn't as a practice cap interest rates for microlenders but does press them not to charge "excessive" rates.

Meanwhile, local mosque leaders have started telling people in the predominantly Muslim community to stop paying their loans. Borrowers have complied en masse.

The mosque leaders are also demanding that lenders give them an accounting of their finances. The lenders say they're not about to comply with that.

The repayment revolt has spread to other communities, including the nearby city of Channapatna, and could reach further across India, observers say.

"We are very worried about this," says Vijayalakshmi Das of FWWB India, a company that connects microlenders with financing from mainstream banks. "Risk management is not a strong point for the majority" of local microfinance providers, she adds. "Microfinance needs to learn a lesson."

Nationwide, average Indian household debt from microfinance lenders almost quintupled between 2004 and 2009, to about $135 from $27 or so, according to a survey by Sa-Dhan, the industry association. These sums are obviously tiny by global standards. But in rural India, the poorest often subsist on just a few dollars a week.

Some observers blame a fundamental shift in the microfinance business for feeding the problem. Traditionally, microlenders were nonprofits focused on community service. In recent years, however, many of the larger microlending firms have registered with the Indian central bank as a type of for-profit finance company. That places them under greater regulatory scrutiny, but also gives them wider access to funding.

This change opened the door to more private-equity money. Of the 54 private-equity deals (totaling $1.19 billion) in India's banking and finance sector in the past 18 months, microfinance accounted for 16 deals worth at least $245 million, according to Venture Intelligence, a Chennai-based private-equity research service.

The influx of private-equity cash is the latest sign of the global rise of microfinance, pioneered by Bangladeshi economist Muhammad Yunus decades ago. On Wednesday, Mr. Yunus, a 2006 Nobel Peace Prize winner, was one of 16 people honored by President Barack Obama with the Medal of Freedom.

"We've seen a major mission drift in microfinance, from being a social agency first," says Arnab Mukherji, a researcher at the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, to being "primarily a lending agency that wants to maximize its profit."

Making loans in poorest India sounds inherently risky. But investors argue that the rural developing world has remained largely insulated from the global economic slump.

International private-equity funds started taking notice of Indian microfinance in March 2007. That's when Sequoia Capital, a venture-capital firm in Silicon Valley, participated in a $11.5 million share offering by SKS Microfinance Ltd. of Hyderabad, India, one of the world's largest microlenders.

"SKS showed the industry how to tap private equity to scale up," said Arun Natarajan of Venture Intelligence.

Numerous deals followed with investors including Boston-based Sandstone Capital, San Francisco-based Valiant Capital, and SVB India Capital Partners, an affiliate of Silicon Valley Bank.

As of last December, there were over 100 microfinance-investment funds globally with total estimated assets under management of $6.5 billion, according to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, or CGAP, a research institute hosted at the World Bank.

Over the past year, investors have poured more than $1 billion into the largest microfinance funds managed by companies, a 30% increase. The extra financing will allow the industry to loan out 20% more this year than last, much of it to countries such as the Ukraine, Cambodia and Bosnia, CGAP says.

Here in Ramanagaram, Lalitha Sharma recalls when the first microfinance firm arrived seven years ago. Those were heady times for her fellow slum-dwellers: Money flowed freely. Field agents offered loans to people earning as little as $9 a month.

They came to Ms. Sharma's door, too. She borrowed $126. Under the loan's terms, she said she would use it to finance a small business — a snack stand she runs with her husband. Many microfinance providers require loans to be used to fund a business.

But Ms. Sharma, a 29-year-old mother of three, acknowledges she lied. "You have to mention a business to get a loan," she says. "There was no other way to get the money." She used it to pay overdue bills and to buy food for her family. Ms. Sharma earns $8 a week, on average, in a factory where she extracts silk thread from cocoons.

Over the next four years, she took nine more loans from three different lenders, in progressively larger sums of $209, $272, $335 and $390, according to lending records reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. A spokesman for BSS Microfinance Private Ltd. of Bangalore, another of her lenders, declined to comment on her borrowing history, citing central-bank privacy rules.

This year, she took another $314 loan to pay for her brother-in-law's wedding, again saying the money would be used for business purposes. She also juggled loans from two other microlenders — $115, $167 and $251 from the Bangalore lender Ujjivan, and $230 from Asmitha Microfin Ltd.

Ujjivan confirmed it issued three loans. An Asmitha official said he had a record of a loan to a Ramanagaram resident named Lalitha, but at a different address.

"I understand that it is credit, that you have to pay interest, and your debt grows," Ms. Sharma says. "But sometimes the problems we have seem like they can only be solved by taking another loan. One problem solved, another created."

Many of the problems in Indian microlending might sound familiar to students of the U.S. mortgage crisis, which was worsened by so-called "no-documentation" loans and by commission-paid brokers. Similarly in India, microlenders' field officers are often paid on commission, giving them financial incentive to issue more loans, according to Ms. Kamath.

Lenders are aware that applicants often lie on their paperwork, says Ujjivan's founder, Samit Ghosh. In fact, he says, Ujjivan's field staffers often know the real story. But his organization maintained a policy of "relying on the information from the customer, rather than our own market intelligence."

He says that policy will now change because of the trouble in Ramanagaram. The lender will "learn from the situation, so it won't happen again," he says.

It's tough to monitor how borrowers spend their money. Ujjivan used to perform regular "loan utilization checks," but stopped because it was so costly. Now it only checks in with people borrowing more than $310, Mr. Ghosh says.

BSS checks how loans are being spent a week after disbursing the money, and makes random house visits, according to S. Panchakshari, its operations manager. The company doesn't have the power to insist that borrowers not take loans from multiple lenders, he said in an email.

Lenders also tend to set up shop where others have already paved the way, causing saturation. There is a "follow-the-herd mentality," says Mr. Ghosh at Ujjivan. Microlenders "often go into towns where they see one or two others operating. That leaves vast chunks of India underserved, "and then a huge concentration of microfinance in a few areas."

In Ramanagaram district, seven microfinance lenders serve 22,500 women (most microloans go to women because lenders consider them less likely to default than men). Loans outstanding here total $4.4 million, according to the Association of Karnataka Microfinance Institutions, a group of lenders.

Lenders in Ramanagaram say the loan-repayment revolt was instigated in part by Muslim clerics who oppose the empowerment of women through microfinance. Most lenders are still servicing loans to Hindu borrowers, but have stopped issuing fresh loans to Muslims. "We can't do business with Muslims there right now," says Mr. Ghosh. "Nobody wants to take that kind of risk."

The irony is that, for years, Indian microlenders have touted themselves as bankers to the nation's impoverished minority Muslim community, which has long been excluded from the formal banking sector.

A 2006 report commissioned by India's prime minister found that while Muslims represented 13% of India's population, they accounted for only 4.6% of total loans outstanding from public-sector banks.

Islam prohibits the paying of interest, but mosque officials don't cite that as the reason for the loan-payment strike. They stressed the overindebtedness of the community, and the strains it's putting on family life.

Ramanagaram's period of wild borrowing irks some residents, both Hindu and Muslim. Alamelamma, a 28-year-old vegetable seller, says that she has benefited from microfinancing and that the profligate borrowers "have ruined it for the rest of us."

One gully away, Ms. Sharma, the heavy debtor, has a different view: She would like to see the microlenders kicked out of the community entirely. "Not just for now, but forever," she says.

![[gold prices]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AY670_Goldhe_NS_20090908162141.gif)

![[job losses]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AY321_DEMONH_NS_20090818191526.gif)

![[Intelligent Investor]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AY532_WINVES_D_20090904115634.jpg)

![[where credit is due]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AR090_MFIjum_NS_20090812192845.gif)