Home » Uncategorized (Page 40)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Employment Snapback?

Milton Friedmans’ monetary model and his famous line that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” are known to many people, but one another hypothesis from Milton on business cycle rarely caught people’s attention.

The so called “plucking model” hypothesizes that the farther you pull it (the economy), the more forcefully it snaps back. Translated into plain English and apply it to business cycle theory, it indicates the sharper the economic downturn, the faster the recovery will be (a.k.a., V-shaped recovery).

The recent empirical research seems to validate such view. And we also tend to observe such pattern in employment recoveries in the pass recessions (see picture below).

(click to enlarge; graph courtesy of calculatedrisk)

Many people argue (e.g. Paul Krugman) that the unemployment in this recession will probably follow the pattern in 1991 and 2001 recessions, i.e. the employment recovers in a very slow pace, leading to the so-called jobless recovery. But if we look at the graph above carefully, the job losses in 1991 and 2001 recessions were also two of the shallowest. So does this indirectly validate Friedman’s view: the less severe the economic downturn, the slower the employment recovers??? Vice versa?

Anyway, if Friedman’s “plucking” hypothesis were true, we are likely to see both investment and employment come back pretty quickly this time around.

(A word of caution: Every recession is different. Given the uniqueness of the great deleveraging and how hard the financial sector was hit in this recession, I am still skeptical that a quick V-recovery is the likely scenario. But I am open minded. I certainly hope I was wrong. )

One last word: these days, we are filled with all kinds of alphabetical predictions: V, W, U, or L, you name it. Now sounds if we haven’t had enough, Jeremy Grantham of GMO, in his most recent investment newsletter, came out another possible scenario: the VL-shaped recovery, i.e., a V-recovery initially then the economy falls back to a long anemic growth path, which he calls Very Long (VL) Recovery. It’s quite an interesting analysis. You can read his newsletter here.

B- for stress test

Wall Street Journal gave a B minus to government-led stress test on major banks:

The government's bank stress tests deserve a B-minus.

To give a sustained boost to investor confidence, the tests needed demonstrable rigor. They achieved that up to a point. While worst-case loss rates look tough, certain loan portfolios — in particular commercial real estate — at some banks seem to have gotten off lightly. Meanwhile, the tests' numbers for underlying earnings — which are needed to offset soaring credit losses — could turn out to be optimistic in some cases.

It is hard to quibble with most of the government's worst-case loss rates, which are calculated for this year and next. For example, an 8.8% loss rate for first-lien mortgages seems suitably tough, even when taking into account the aggressive underwriting during the housing bubble. The government's 13.8% worst-case loss-rate for second-lien mortgages seems fair. But it is a stretch to think Wells Fargo, with its large home-equity book focused on stressed housing markets, will have a lower-than-sector loss rate of 13.2%.

The government may have been too optimistic in positing an 8.5% commercial-real-estate loss rate. This sector is just starting to fall apart, and defaults may move sharply higher as borrowers struggle to refinance loans. BB&T's commercial-real-estate worst case is higher at 12.6%, but its portfolio may arguably show higher losses.

The government's earnings projections also need to be taken with a pinch of salt. It is optimistic to assume banks can repeat their first-quarter revenue generation, for instance. Given the Fed has unleashed a tidal wave of liquidity into the system, interest rates are going to be extremely volatile for several quarters, making bank revenue very hard to predict.

Another reason to be skeptical is few banks have to substantially increase overall levels of Tier 1 capital, which includes common and preferred shares, by raising new money. The government is effectively saying most large banks were solidly capitalized even when investors fled earlier this year.

Instead of immediately raising overall capital levels, some banks are just shifting the mix toward common equity — the highest-quality capital. Lenders that need to raise fresh money include GMAC, General Motors' lending arm. Also, Wells Fargo's offering of common stock, announced Thursday, suggests its overall capital will increase.

Finally, the government has effectively said it wants banks to have Tier 1 common stock equivalent to 4% of risk-weighted assets. First, investors have to decide whether they have confidence in the risk weightings.

Second, Tier-1 measures of capital leave out certain unrealized losses on securities that could become real later — something captured by tangible-common-equity ratios.

Then they must decide whether 4% — which still translates into 25-to-1 leverage — is safe for the unpredictable environment we are in.

China’s College Bubble

Inspired by the recent report on Wall Street Journal that China is facing a college grad glut with millions of college grads failing to find job upon graduation, in this short note I dig deeper into China’s college boom and briefly analyze what happened in the last decade in China’s higher education.

According to the Journal article, in 2009, “up to one-third of last year’s 5.6 million university graduates are still looking for work, and this year will see another 6.1 million hit the labor market”. The graph below shows a snapshot of a typical job fair for college job seekers. It is always crowded.

The following graph draws data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics and it shows that starting from 1999, China began its aggressive college expansion, pushing the annual college enrollment number from 1 million in 1998 to about 5.5 million in 2007. The rise was very sharp and dramatic.

(click on the graph to enlarge)

Next, I look at the average college acceptance rate, which is defined as the accepted college students each year as a percentage of the annual high school graduates. Again, we observe a similar jump in acceptance rate beginning in 1999, from a little over 40% in 1998 to staggering 84% in 2002. The rate since then has leveled off to 70%, which means 7 out of 10 high school graduates go to college in China. For a developing country, this is an AMAZING number.

Economic theory tells us if there is an oversupply of college students, either the demand for college grads quickly catches up, or college students have to find their own way out. Otherwise, there will be a glut of labor supply. So what are the alternative routes?

The most natural solution is to go to graduate school. The strategy is, “hide in grad school and become more competitive”. This incentive exists everywhere in the world. In the US, the current recession surely will help lift graduate school enrollment.

The following graph looks at the correlation between annual college graduates and annual enrollment of domestic graduate school. What we observe is in the last three decades college graduates and graduate school enrollment went hand-in-hand with each other. In 2002, about 420,000 college grads went for graduate study, accounting for 15% percent of total college graduates. In 1998, the number was 8%.

Alternatively, for better or for worse, people choose to go to overseas. A degree from foreign countries, especially from the US, is believed to give students more comparative advantage, and the relatively easy and open US immigration policy also played a role. The graph below looks at the correlation between college grads and students who went to overseas study. Again, we observe a sharp jump around the millennium. After 9/11, the number trended down but started to go up again in 2005. In 2007 alone, about 140,000 Chinese students went to overseas.

There are many reasons Chinese students chose to go to overseas, but the domestic labor market pressure certainly is one of the most important contributing factors.

In the long run, more people with higher education is good for China’s economic growth and development. In the short run, China has to solve the mismatching problem in the labor market.

Is China leading the world out of mess?

Following my previous post on the strong indication that Chinese economy is recovering and the misplaced belief that the collapse of world trade will drag Chinese economy down to its knees, more recent data show China is possibly leading the world, especially the commodities countries like Australia and Brazil, out of the tunnel early.

(click on the graph for further video analysis)

(source: FT)

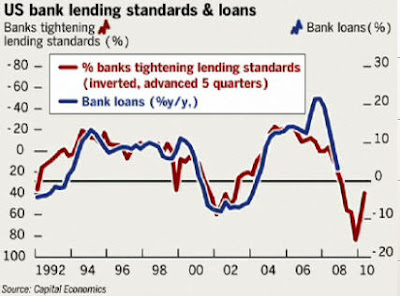

Credit less crunched

Click to view the video on indicators that credit crunch is beginning to level off.

Meltzer: Inflation Nation

Allan Meltzer, economist and historian of the Fed, argues deflation is not to worry and what we should worry about is inflation (source: NYT). Meltzer, like Gary Becker in my previous post, again questions the Fed's ability to remain independent in face of government pressure to monetize the huge budget deficits.

IN the 1970s, with inflation rising, I often described the Federal Reserve as knowing only two speeds: too fast and too slow. At the time, the Fed’s idea was to combat recession by promoting expansion, printing money and making it easier for businesses and households to borrow — and worry only later about the inflation that resulted. That strategy produced a sorry decade of slow productivity growth, rising unemployment and, yes, rising inflation. If President Obama and the Fed continue down their current path, we could see a repeat of those dreadful inflationary years.

Back then, as now, the members of the Fed were well aware of the harmful effects of inflation. In private, they vowed not to let it get out of hand and several times even started to do something about it. But when their anti-inflationary moves caused the unemployment rate to rise to 6.5 percent or 7 percent, they forgot their promises and again began expanding the money supply and reducing interest rates.

By 1979, reported rates of inflation, worsened by the oil shock, had reached double digits. Opinion polls showed that the public now considered inflation to be the main economic problem. President Jimmy Carter’s choice for chairman of the Fed, Paul Volcker, said that he would fight inflation more deliberately than his predecessors. The president agreed with him, as did the chairmen of the Congressional banking committees.

With the public acceptance of the importance of low inflation, support in the administration and in Congress, and a chairman committed to the task, the Fed finally set out to correct what it had too long neglected. Instead of working only to avoid unemployment, the Fed sought to bring inflation back under control. Instead of flooding the market and banks with money, the Fed tightened its reserves. And instead of keeping interest rates in a narrow, relatively low range, Mr. Volcker let the market dictate the interest rate, allowing the prime rate to go as high as 21.5 percent. These disinflation policies continued in earnest with the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan.

Even so, the public, having already seen three or four failed attempts to tame inflation, didn’t really believe that Mr. Volcker and President Reagan would stay the course. In my reading of the evidence, a decisive change in attitudes occurred only in the spring of 1981, when the Federal Reserve raised interest rates even though the unemployment rate was approaching 8 percent. This was new. This was different. People began to expect lower inflation and, in this belief, slowed the increase in wages and prices, contributing to the decline in actual inflation.

Naturally, there were critics. But their criticisms were not strong enough to reverse policy. At the 1982 convention of the National Association of Home Builders, Paul Volcker said that if he were to let up on anti-inflation efforts prematurely, “the pain we have suffered would have been for naught — and we would only be putting off until some later time an even more painful day of reckoning.” As always in periods of high interest rates, home builders had been especially badly hurt, but when the chairman finished his speech, they gave him a standing ovation. Though they disliked his policy, they admired his determination to do what was needed.

The pain did not end. And the anti-inflation policy continued until the unemployment rate rose above 10 percent, many savings and loan institutions faced bankruptcy, and most Latin American countries defaulted on their debt. These were the unavoidable side effects of the public’s gradual adjustment to the new economic environment. This process continued until 1983, when the reported inflation rate fell below 4 percent.

Paul Volcker is now the head of President Obama’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board. Mr. Volcker and the administration’s many economic advisers are all fully aware of the inflationary dangers ahead. So is the current Fed chairman, Ben Bernanake. And yet the interest rate the Fed controls is nearly zero; and the enormous increase in bank reserves — caused by the Fed’s purchases of bonds and mortgages — will surely bring on severe inflation if allowed to remain. Still, they all reassure us that they can reduce reserves enough to prevent inflation and they are committed to doing so.

I do not doubt their knowledge or technical ability. What I doubt is the commitment of the administration and the autonomy of the Federal Reserve. Mr. Volcker was a very independent chairman. But under Mr. Bernanke, the Fed has sacrificed its independence and become the monetary arm of the Treasury: bailing out A.I.G., taking on illiquid securities from Bear Stearns and promising to provide as much as $700 billion of reserves to buy mortgages.

Independent central banks don’t do what this Fed has done. They leave such fiscal action to the legislative branch. By that same token, Mr. Volcker’s Fed had to avoid financing the large (for that time) Reagan budget deficits to be able to bring down inflation. The central bank was made independent expressly so that it could refuse to finance deficits. But is there a political consensus that the much larger Obama deficits will not pressure the Fed to expand reserves to buy Treasury bonds?

It doesn’t help that the administration’s stimulus program is an obstacle to sound policy. It will create jobs at the cost of an enormous increase in the government debt that has to be financed. And it does very little to increase productivity, which is the main engine of economic growth.

Indeed, big, heavily subsidized programs are rarely good for productivity. Better health care adds to the public’s sense of well-being, but it adds only a little to productivity. Subsidizing cleaner energy projects can produce jobs, but it doesn’t add much to national productivity. Meanwhile, higher carbon tax rates increase production costs and prices but do not increase productivity. All these actions can slow productive investment and the economy’s underlying growth rate, which, in turn, increases the inflation rate.

Some of my fellow economists, including many at the Fed, say that the big monetary goal is to avoid deflation. They point to the less than 1 percent decline in the consumer price index for the year ending in March as evidence that deflation is a threat. But this statistic is misleading: unstable food and energy prices may lower the price index for a few months, but deflation (or inflation) refers to the sustained rate of change of prices, not the price level. We should look instead at a less volatile price index, the gross domestic product deflator. In this year’s first quarter, it rose 2.9 percent — a sure sign of inflation.

Besides, no country facing enormous budget deficits, rapid growth in the money supply and the prospect of a sustained currency devaluation as we are has ever experienced deflation. These factors are harbingers of inflation.

When will it come? Surely not right away. But sooner or later, we will see the Fed, under pressure from Congress, the administration and business, try to prevent interest rates from increasing. The proponents of lower rates will point to the unemployment numbers and the slow recovery. That’s why the Fed must start to demonstrate the kind of courage and independence it has not recently shown.

Milton Friedman often said that “inflation was always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” The members of the Federal Reserve seem to dismiss this theory because they concentrate excessively on the near term and almost never discuss the medium- and long-term consequences of their actions. That’s a big error. They need to think past current political pressures and unemployment rates. For the next few years, they cannot neglect rising inflation.

Allan H. Meltzer, a professor of political economy at Carnegie Mellon University, is the author of “A History of the Federal Reserve.”

Living Capitalism

A 1948 cartoon about capitalism.

Tags:

George Soros: The great speculator

An interview of George Soros on his view of the economy:

![[Timothy Geithner]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AW603_Stress_NS_20090507184435.gif)