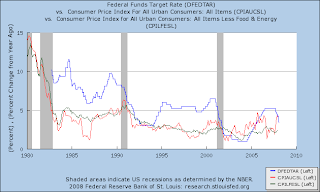

The same voices that supported tough macroeconomic policies to deal with the excesses of spending and borrowing in east Asia, Russia and Latin America are today pushing for a significant relaxation in the US to deal with the so-called subprime crisis. Interest rates should be slashed quickly and $150bn put into taxpayers’ pockets by April at the latest, they say. The Fed cut by another half-point on Wednesday.

The goal seems to be to avoid a 2008 recession at all costs. As Larry Summers, former Treasury secretary, put it, failure to act would make Main Street pay for the sins of Wall Street.

It is easy to lose sight of the overall picture. Main Street consumers have overspent and over-borrowed and are unable to meet their obligations. The fact that households may have so behaved because they were enticed by “teaser loans” does not change the facts; it only assigns blame. Consumption has been above sustainable levels and needs to adjust down, whatever view one has about the responsibility of adults over their financial decisions.

The adjustment of private consumption to sustainable levels is necessary, but is likely to have a negative influence in the short run on the growth of aggregate demand, of which it represents more than 70 per cent. It is hard for this adjustment to take place without bringing down the rate of growth of gross domestic product, possibly to negative numbers.

It will also lower the US external deficit and put downward pressure on world growth. That is a consequence of the imbalances accumulated over five years of unprecedented world growth. Returning to a sustainable path is good for the US and the world economy over any horizon that assigns some value to what happens after 2008. Sustainable growth is not the consequence of an unsustainable consumption boom but of the progress and diffusion of science, technology and innovation – which show no sign of slowing down.

An efficient adjustment to the US over-consumption imbalance (and Chinese under-consumption) in a way that does not hurt longer-term growth should be based on compensating for the decline of US consumption with an increase in domestic investment and in consumption abroad. It should not be based on giving the US consumer more rope with which to hang himself.

Hence, macroeconomic policy should not be based on a panicky attempt to avoid a 2008 recession at all costs but on a forward-looking strategy that achieves the needed reduction in consumption at the lowest cost in terms of the stable growth. This is not achieved by giving US households a $1,000 cheque by April, a trick that no macroeconomic textbook would argue is particularly effective. If there is fiscal room – a big if, given the weak structural position of the US government and its likely cyclical worsening – it would be better spent in accelerating investments in plant and equipment via accelerated depreciation schemes, to improve the capacity of the economy to keep on growing after the crisis.

The logic behind monetary easing is also suspect. Much of it is automatic, as central banks pump in money just to keep interest rates steady. It is understandable that politicians facing a November election and bankers with a lot of their money at stake should feel that this is the worst crisis ever and have an obvious interest in exaggerating the consequences for Main Street.

They all assume that if banks lose capital, they will stop lending. This is what happens in developing countries because of incomplete financial markets, but is not what one would expect in the world’s most sophisticated capital market. In fact, bank capital has already been lost and the solution is not to put more air into the bubble but to put more capital into banks. This is already happening: Citibank, UBS, Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley have raised more than $100bn from foreign investors and sovereign wealth funds. Authorities might use their moral suasion to accelerate this process.

The US should face its need for adjustment with courage and reason, not fear. It should stop behaving as the whiner of first resort, ready to waste all its dry powder on a short-sighted attempt to prevent a 2008 recession. Many poorer countries with weaker markets and institutions have survived and benefited from an adjustment that involves a year of negative growth. Faster bank recapitalisation, fiscal investment stimulus and international co-ordination should be first on the policy agenda.

The writer is the director of Harvard University’s Center for International Development

![[Get Real!]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ED-AH013_rattne_20080128174755.jpg)

![[AOT]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AO856_AOT_20080128184433.gif)

![[The Loss Where No One Looked]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AO846_Howdun_20080127203211.gif)

![[chart]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AO746_BVIEWS_20080121215750.gif)