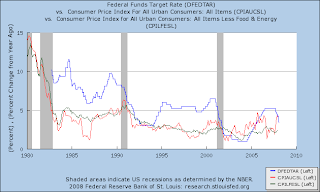

Fed to Cut Funds Rate Below Inflation

(green: core inflation red: headline inflation)

see Bloomberg article on the same topic.

Let’s Get Real About the Economy

Like stopped clocks that are right twice a day, the Greek chorus of perennial economic pessimists is chortling. At last, their Cassandra-like chanting has moved to center stage, amplified by the megaphone of last week's Davos gabfest. Nouriel Roubini, a New York University economist, sees a recession that will be "ugly, deep and severe." From Morgan Stanley's Stephen Roach: a potential economic "Armageddon" (a 2004 warning). Even the esteemed George Soros calls the current situation "the worst market crisis in 60 years."

Worse than the early '80s, when wildly exuberant lending thrust a thousand savings and loans into insolvency, and some major U.S. bank stocks plunged to single digits? Worse than 1981, when the Federal Reserve drove its key interest rate to 19% in an effort to staunch inflation? Remember the 1970s, when our economy was mired in stagflation? More painful than the dot-com hangover — hardly a distant memory — when the Nasdaq fell by 78% amidst widespread corporate bankruptcies? Let's get real.

![[Get Real!]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ED-AH013_rattne_20080128174755.jpg)

Make no mistake, the U.S. economy is weak and getting weaker. Recession odds have elevated to Condition Red. And hard experience confirms that detecting downturns is far easier through a rearview mirror than through the windshield. But the probability remains that what our economy faces is less a plunge into the dark ages than a cyclical purging of excesses — perhaps akin to the eight-month recession in 2001.

While the suddenness of the slowdown and extent of the turmoil in financial markets surprised many, the inevitability of a correction should have been evident. We've been aware for years that housing prices had soared well above their historic relationship to personal income. Americans were consuming beyond their means. Risk premiums — the extra amount that investors get paid for buying paper other than Treasuries — had fallen to record low levels that were clearly unsustainable. As those bubbles continued to inflate, we've known that the magnitude of the inevitable correction was growing.

It's easy to understand the fear that has enveloped our financial system, a fear grounded in the complexity and lack of transparency associated with the rise of increasingly esoteric derivatives with equally opaque names — credit default swaps, CDOs, RMBSs and the like. But remember that the same derivatives that are now terrifying even major financiers are what have increasingly allowed banks to spread risk in a way that was never before possible.

Some of that risk was exported. That's why financial institutions across the world and even small towns in Norway are feeling the pain of subprime losses in the U.S. while our banks remain solvent, able to absorb their portion of the write downs. Contrast that to the consequences of the bout of overeager lending two decades ago, when major institutions like the Bank of New England went bankrupt and still larger banks nearly toppled.

So pronouncing the demise of the world's most productive economy is surely premature. Count among our other blessings a flexibility that has kept inflation low and given the Federal Reserve the scope to reduce interest rates without triggering inflationary fears. Even as rates have been lowered by 1.75 percentage points since last summer, inflationary expectations, as measured by Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, have slid (from 2.7% in June to around 1.8% today).

Compare that to Europe, where a stubbornly higher inflation rate has tied the hands of the European Central Bank. Would we really prefer to trade our economy for that of old Europe?

Accompanying the cries of the Cassandras has been another (sometimes overlapping) chorus of diatribes aimed at policy makers working to soften the pain of the adjustment process. Many of those jeremiads have been aimed at the Federal Reserve for having acted either too quickly or too slowly and, of course, for having created the problem in the first place by keeping interest rates too low for too long.

Anyone can call plays from the bleachers. But just as we don't stand over doctors in an emergency room, we need to lay off the Federal Reserve and its chairman, Ben Bernanke. No doubt, history will find some fault with Mr. Bernanke's real-time decision making. But given the uncertain and fast changing dynamics, the Fed should be commended, not demeaned, for its actions thus far.

At the same time, monetary policy can't by itself provide the spark that the economy needs. For one thing, relying completely on lower interest rates jeopardizes the progress that's been made since last summer in convincing markets that, yes, bad investment decisions will lead to losses. For another, monetary policy, which operates through lower interest rates, aids some — but not all — corners of the economy.

That's why we need to get behind last week's remarkable agreement between the White House and Democratic lawmakers on a stimulus package of tax cuts and rebates. Instead of yet another round of carping, congratulations should be offered, particularly to Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, for bridging difficult partisan differences.

No doubt, anyone could find fault with aspects of the package. For my part, I'd happily part with the ineffective accelerated depreciation and add a dollop of extended unemployment benefits. But of all the stimulus measures that have been assembled in our Washington sausage factory in past decades, this may well be the best, and the Senate needs to get over its hurt feelings about being left out of the negotiations.

This package need not be the end of our efforts to address our economic challenges, particularly the plight of homeowners. While the proposed legislation offers some hope for easing the mortgage crunch, more should be done.

In particular, we should reach back to the Depression and consider resurrecting the Home Owners' Loan Corporation. Created in 1933, that long-forgotten agency bought defaulted mortgages from savings-and-loan institutions at discounts to face value and then negotiated new terms with stretched homeowners to avoid foreclosure. By the time it finally closed down in 1951, the HOLC had aided one in five mortgaged dwellings and had even turned a small profit for the government.

We also should reform the patchwork of government regulators overseeing our financial institutions, to provide more coherence. While Alan Greenspan's Fed shouldn't be blamed for keeping rates low for too long (would we really have wanted slower growth these last five years?), it did ignore its responsibilities to regulate predatory lending. (Too much Ayn Rand and not enough FDR.) Additionally, with the internalization of financial markets, attention should be paid to Mr. Soros's excellent suggestion of more globally coordinated regulation.

Ironically, America's most serious economic challenges are almost surely the ones currently receiving the least amount of attention. Let's not forget that income inequality has risen to record and unacceptable heights. Nor should we lose sight of vast unfunded future obligations — $50 trillion, by some government estimates — for social welfare programs, particularly Medicare. Finally, as presidential candidates on the campaign trail remind us regularly, we have important unmet needs, ranging from health care to infrastructure.

While further stresses are inevitable as the adjustment process continues, our economic bedrock remains fundamentally strong. We have the means to continue to prosper, as long as we don't panic just when we should be getting down to work.

Mr. Rattner is managing principal of the private investment firm Quadrangle Group LLC.

—

**************************************

Paul D. Deng

Department of Economics

Brandeis University

IBS, MS 032

Waltham, MA 02454

http://www.pauldeng.com

Bernanke might will be a hero

It's Not Time To Judge

Bernanke YetBy JON HILSENRATH

January 29, 2008; Page C1, WSJBen Bernanke can't get a break.

Two weeks ago, the Federal Reserve chairman's critics complained he was standing idly by while the markets sank, and they clamored for more-aggressive action. Last week, when he did what they asked, they called him a pawn of fickle investors. Had he done nothing, the same critics probably would have said he was ignoring the potential economic damage of a stock-market collapse.

![[AOT]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AO856_AOT_20080128184433.gif)

In the end, all this hand-wringing about Mr. Bernanke's style and demeanor will be long forgotten if the Princeton professor gets his economics right. He's betting he can head off a recession by quickly lowering interest rates, possibly again tomorrow after the Fed meets. And he's betting he can do it without igniting inflation.

It's a stark choice and stands in clear contrast to his counterpart at the European Central Bank, Jean Claude Trichet. Mr. Trichet, who says he's more worried about inflation, hasn't moved rates at all.

It probably doesn't help Mr. Bernanke that he has to manage the situation while his former boss, Alan Greenspan, and potential successor, Lawrence Summers, chime in with opinions from places like Davos and from book tours.

If the U.S. economy somehow gets out of this mess without a recession and with inflation under control, Mr. Bernanke will be a hero regardless of what market critics say now. Wall Street might give his policies a chance before writing him off.