Treasury yields signal the US heading into long slump

An update on my previous post, QE3 is coming (source: CNBC):

The impact of a US debt downgrade

Friday’s downgrade by S&P of the US sovereign debt, from AAA to AA+, was an extraordinary event in modern finance. As reported by WSJ, the is the first time the US government debt lost its AAA credit rating in more than 70 years.

What does this mean for the US and world economy? Here is an insightful interview of Nouriel Roubini (aka Dr. Doom), Christina Romer (former Chairman of President’s Council of Economic Advisors), and Jim Bianco (president of Bianco Research).

US Treasurys are widely held as collateral by many financial institutions around the world. The biggest risk is a sharp fall in value of US Treasurys may trigger another credit dry-up in the financial system. This is perfectly summarized in the following paragraphs in the WSJ piece:

J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. analysts estimate some $4 trillion worth of Treasurys are pledged as collateral by borrowers such as banks and derivatives traders. If that collateral isn’t considered as high quality by lenders, the borrowers could be required to cough up more cash or securities to put the minds of lenders at ease.

That could force investors to sell off other assets to come up with the money. In a worst case scenario, credit markets could seize up, as they did during the Lehman Crisis.

Money market funds held by millions of Americans hold some $1.3 trillion in securities directly or indirectly exposed to Treasury and government agency securities, as well as short-term loans to financial institutions, known as repos, which are backed by Treasurys. Experts say that the downgrade won’t force money market funds to sell. But there are still risks.

If Treasurys tumble in value, funds will be forced to mark down their holdings, raising the potential for some to “break the buck” as the Reserve Primary fund did during the worst of the financial crisis.

Lastly, let’s hope China and Japan won’t sell: a key concern will be whether the appetite for U.S. debt might change among foreign investors, in particular China, the world’s largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasurys. In 1945, foreigners owned just 1% of U.S. Treasurys; today they own a record high 46%, according to research done by Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

In theory, China and the US are on the same boat: a fall in US Treasurys won’t do Chinese any good. But that’s only theory on paper: people do all kinds of things when they panic. Same thing applies to governments. Personally, I think the chance is very slim for Chinese to dump US Treasurys. But always be reminded “what could happen” – Re-watching this 2009 interview of Julian Robertson of Tiger Management will help you appreciate the worst scenario.

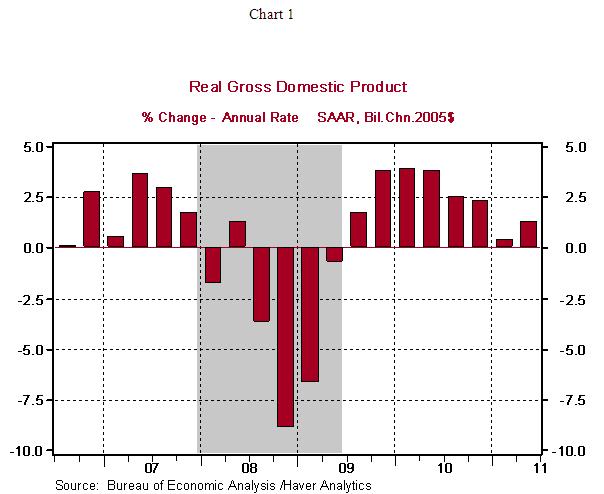

Digest latest GDP number

Real GDP in Q2 2011 is estimated to grow at only 1.3% annualized rate, while Q1 GDP growth was significantly revised down from 1.9% to mere 0.4%. This was achieved despite the Fed’s two rounds of quantitative easing.

The recovery of the US economy seems having lost its momentum. Here is a chart from Nothern Trust’s research team.

So far, the recovery since summer 2009 has failed to pull the US economy back to its pre-peak level achieved in late 2007 (see this nice graph from calculatedrisk, click to enlarge).

John Silvia, chief economist at Wells Fargo, describes the latest growth number as the “worst of all worlds”. And he is worried that the inflation in the US is creeping up in the face of high unemployment – you know where we are heading, do you?

Long-term unemployment

According to Labor Dept., in 2010 on a national level, a little over 25% of the unemployed had been out of job for over 52 weeks. In New Jersey, Georgia, Michigan, South Carolina, North Carolina, Illinois and Florida, more than a third of unemployed residents had been out of work for at least a year. New Jersey was the worst among the worst bunch: 37.1% of the jobless had been out of work for at least a year.

WSJ also has a nice interactive chart of long-term jobless rate by each state (link). You will notice, even in Texas, a state with one of the strongest economies, over 20% of the unemployed had been out of work for a year.

Here below is a chart from CalculatedRisk that tracks the long-term unemployment (for more than 26 weeks, or half a year) since 1960s. I don't need to say a thing – you immediately see how serious the problem is.

We are heading into another 70s – the only difference is we have yet to see high inflation – just not yet.

Gold passing $1,600 – but don’t sell yet

In an era when US dollar, Euro, and Yen are competing for 'which is the worst currency', and when emerging markets are suffering from high inflation and asset bubbles, hold on to your gold.

Long-term investors should not worry about the ups and downs in the short term. Until real interest rate turns positive, don't sell.

Here are a couple of very nice charts from Dr. Yardeni. Click to enlarge.

It's the extraordinary time that makes investing so exciting…

How governments use financial repression to pay down their debt

Economist Magazine recently had a fantastic article on the history of how government could use 'financial repression' to pay down their debt. Here below are my summary and some highlights. You certainly will see some of the same gimmicks will be repeated during this debt liquidation process.

To pay down government debt, essentially, there are 3+1 ways:

1) Grow out of it, with income from economic growth being subtracted by interest rate payments. As long as the income is greater than interest payment, this will work out;

2) Tax out of it – this requires some real sacrifice of the country and its countrymen. Ironically, higher tax often inhibits faster economic growth, especially when the economy is already quite weak, so most economists will probably advise against it. Higher tax is also not very helpful in controlling government spending;

3) Inflate out of it – the easiest way, and a no-brainer, and governments have been using it all along human history. But it comes with long-term dire consequences. For one, the government may ruin its reputation as a debtor. People, both domestic and foreign, will be less willing to lend in the future, if ever again at all.

In the case of the United States, since a lot of government debts are held by foreigners, it's even easier to let foreigners foot the bill by printing money, as long as the whole international financial system, based on the US dollar, won't collapse (the bet is Chinese and Japanese are stuck into 'dollar trap' – they have no choices, so inflate while you still can). The long-term consequence is US dollar loses its status as international reserve currency. Some sort of new international monetary system will eventually emerge.

4) Lastly, the 4th way – rolling over into new debt with lower interest rate. This is often combined with an inflation rate that is higher than the nominal interest rate. With real interest rate being negative, government essentially solves its liquidity problem by financing its borrowing through lower interest and reduces its debt load through inflation.

Now, the excerpts from Economist:

Following the second world war many countries reduced debt quickly without messy defaults or painful austerity. British debt declined from 216% of GDP in 1945 to 138% ten years later, for example. In the five years to 2016, by contrast, British debt as a proportion of GDP is expected to drop by just three percentage points despite a harsh austerity programme. Why was it so much easier to cut debt in the immediate aftermath of the war?

Inflation helped. Between 1945 and 1980 negative real interest rates ate away at government debt. Savers deposited money in banks which lent to governments at interest rates below the level of inflation. The government then repaid savers with money that bought less than the amount originally lent. Savers took a real, inflation-adjusted loss, which corresponded to an improvement in the government’s balance-sheet. The mystery is why savers accepted crummy returns over long periods.

The key ingredient in the mix, according to research by Carmen Reinhart of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Belen Sbrancia of the University of Maryland, was “financial repression”. The term was first coined in the 1970s to disparage growth-inhibiting policies in emerging markets but the two economists apply it to rules that were common across the post-war rich world and that created captive domestic markets for government debt.

…

Repression delivered impressive returns. In the average “liquidation year” in which real rates were negative, Britain and America reduced their debt by between 3% and 4% of GDP. Other countries, like Italy and Australia, enjoyed annual liquidation rates above 5%. The effect over a decade was large. From 1945 to 1955, the authors estimate that repression reduced America’s debt load by 50 percentage points, from 116% to 66% of GDP. Negative real interest rates were worth tax revenues equivalent to 6.3% of GDP per year. That would be enough to move America’s budget to surplus by 2013 without any new austerity programme.

Cafes as Innovation Incubator

Cafe as meeting place for ideas and many billion-dollar dreams.

Which emerging market is overheating?

Economist Magazine constructs a nice overheating index for emerging markets. The index includes six macro factors: inflation, output gap, unemployment, excessive credit expansion, real interest rate, and current account.

According to the index, the most overheated emerging market is Argentina, and it is followed by Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and Vietnam.

China lies in the mid of the pack – given China’s recent wave of tightening, the risk is low for China, IMO.

For details of ranking for each factor, use link here.