Bill Gross: The US could lose AAA rating

Stimulating economy without concern over long-term fiscal budget won’t go long forever. This even applies to the US, which has retained its AAA rating on government debt since WWI. Report from Reuters:

Bill Gross, manager of the world’s biggest bond fund, warned on Thursday the United States will eventually lose its top AAA credit rating, a fear that had already spooked financial markets on Thursday and could keep the dollar, stocks and bonds under heavy selling pressure.

The United States will face a downgrade in “at least three to four years, if that, but the market will recognize the problems before the rating services — just like it did today,” Gross told Reuters.

Gross, the co-chief investment officer of Pacific Investment Management Co. and manager of the Pimco Total Return Fund, which has $154 billion in assets, earlier had told Reuters via email that market declines on Thursday were due to investor fears that the United States is “going the way of the UK — losing AAA rating which affects all financial assets and the dollar.”

Standard & Poor’s on Thursday lowered its outlook on Britain to “negative” from “stable,” threatening the nation’s top AAA rating. Britain faces a one in three chance of a ratings cut as debt approaches 100 percent of gross domestic product.

Read the full article here.

There is also a video interview on this from CNBC:

China’s FDI inflow

According to Bank of Finland:

Foreign direct investment inflows into China declined 21 % y-o-y during January-April. The $6 billion FDI inflow for the month of April translated into a decrease of 23 % y-o-y. Although the contraction from the start of the year appears dramatic, it actually represents a return to more typical levels. FDI inflows were massive in 2008, reaching $108 billion for the year. In the first four months of this year, investments are actually beating the same period in 2007.

More tellingly, the number of projects under implementation has declined each year over the past four years. On the other hand, the average size of a project was growing until the start of this year. Nominally, foreign investment in China is relatively small, representing a mere 7 % of total investment annually. Hong Kong is the largest provider of FDI (about 46 %), and its relative contribution has increased sharply as other countries (including tax havens) have pulled back from investment in China. Combined EU and US investments represent less than of 10 % of total foreign investment at the moment.

The art of Chinese ‘data’ massaging

An interesting analysis from Economist Magazine on the reliability of China's growth data. What I took away from reading this piece is data massaging did exist, but the situation has been improved over the years. The recent official GDP growth number is unlikely to have overstated China's real growth. Maybe a little bit.

PART of the recent optimism in world markets rests on the belief that China’s fiscal-stimulus package is boosting its economy and that GDP growth could come close to the government’s target of 8% this year. Some economists, however, suspect that the figures overstate the economy’s true growth rate and that Beijing would report 8% regardless of the truth. Is China cheating?

Economists have long doubted the credibility of Chinese data and it is widely accepted that GDP growth was overstated during the previous two downturns. In 1998-99, during the Asian financial crisis, China’s GDP grew by an average of 7.7%, according to official figures. However, using alternative measures of activity, such as energy production, air travel and imports, Thomas Rawski of the University of Pittsburgh calculated that the growth rate was at best 2%. Other economists reckon that Mr Rawski was too pessimistic. Arthur Kroeber of Dragonomics, a research firm in Beijing, estimates GDP growth was around 5% in 1998-99, for example. The top chart, plotting the official growth rate against estimates by Dragonomics, clearly suggests that some massaging of the government statistics may have gone on. The biggest adjustment seems to have been made in 1989, the year of political protests in Tiananmen Square. Officially, GDP grew by over 4%; Dragonomics reckons it actually declined by 1.5%.

China’s growth in the first quarter of this year has led some to conclude that the government is up to the same old tricks. According to official figures, GDP was 6.1% higher than a year earlier. Yet electricity production in the first quarter was 4% lower than it had been a year earlier; in comparison, production grew by 16% in the year to the first quarter of 2008. In the past, GDP and electricity output have moved broadly together, although it is not a one-to-one relationship (see bottom chart). But the gap between the two lines is now wider than it has ever been. Given that power statistics are less likely to have been tampered with than politically sensitive GDP figures, is this evidence that the latter have been fiddled?

Probably not. Paul Cavey, an economist at Macquarie Securities, argues that the discrepancy is explained by the fact that energy-guzzling heavy industries, such as steel and aluminium, bore the brunt of the slowdown last year. Mr Cavey calculates that the metals industry accounted for 40% of the growth in electricity consumption in 2001-07, but only 16% of the increase in industrial production. Steel output fell by more than 10% in the year to the fourth quarter, so it is hardly surprising that energy use dropped.

Distrust of the GDP numbers has prompted Capital Economics, a research firm based in London, to create its own proxy of economic activity, which includes electricity output, domestic freight volumes, cargo traffic at ports, passenger transport and floor area under construction. It suggests that GDP growth slowed to only 4% in the year to the first quarter. However, it tracks mostly industrial activity, and thus excludes two-fifths of the economy, most notably services, which are growing faster.

Then there are government tax revenues. These have fallen by 10% over the past year, compared with a surge of 35% in early 2008, suggesting that incomes and output have tumbled. But Stephen Green, an economist at Standard Chartered, says that revenues were inflated in early 2008 by a sharp rise in taxes from the boom in land sales, which has since subsided. Another possible distortion is that local officials may be hiding tax revenue to make their finances appear worse, in order to get more money from Beijing to finance infrastructure projects.

Overall, Dragonomics’s Mr Kroeber thinks that GDP growth in the year to the first quarter of 2009 was not significantly overstated. One reason why others are more suspicious is the fact that the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) does not publish quarterly GDP figures as developed economies do; its year-on-year changes give it more scope to smooth growth rates (for example, output probably did stall over the past two quarters). To be fair, many developing countries do this as well. One reason is that seasonal adjustment is tricky in such countries where the shift from agriculture to industry changes the pattern of seasonality over time, says Mr Kroeber.

And for all today’s misgivings, Beijing’s growth estimates consistently proved to be too low until recently. One of the quirks of Chinese data has long been that the provinces reported higher numbers than the central government did—a phenomenon that was put down to the fact that local officials inflated growth rates in order to get promoted. Yet the NBS GDP figures have almost always been revised upwards. For example, growth in 2007 was first reported as 11.4%, but in January it was marked up to 13%.

The NBS has improved its data-gathering methods in recent years, by extending its coverage of services, for example. This month Beijing also introduced new penalties for officials who falsify statistics. But the real test is whether the government itself is prepared to publish politically embarrassing bad news. There are encouraging signs that it is becoming more open. On May 14th an essay on the NBS website by Xu Xianchun, the bureau’s deputy director, was surprisingly frank about some of the flaws in Chinese statistics. Mr Xu admitted, for example, that the retail-sales numbers include some purchases by companies and the government, which should not be counted as consumption. He estimated that consumer spending in the first quarter grew by 9%, compared with the 15% increase reported for retail sales.

Andy Rothman, an economist at CLSA, a regional broker, believes that Chinese statistics are much more trustworthy than they used to be. This is partly because there are alternative numbers to go on; CLSA, for example, produces its own purchasing-managers’ index. There are also more private-sector economists keeping tabs on China than there were a decade ago. The more eyes there are on China, and the more crucial its economic performance becomes for the rest of the world, the harder it is for officials to tamper with the speedometer.

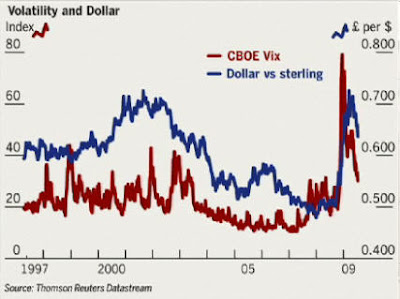

Volatility and the Dollar

With terrible news coming out of UK today, US Dollar still managed to go down against British Pound. So what’s going on with the Dollar?

This market view from FT might help you solve the puzzle.

David Rosenberg bearish on American consumers

Rosenberg says the 25-year consumer credit expansion has come to an end and expect more frugality and don’t expect any quick rebound of American consumption, which accounts for 70% of the US economy and 17% of the world economy.

Swedish view on the rise of China

Interview of Hans Rosling, one of the founders of gapminder.org, on the rise of China. And he asks people not to ignore the speed and the magnitude of China’s unprecedented rising.

(sidenote: the interview should’ve taken at a better place)

What if China is just stockpiling?

There has been a lot of talk that the rebound of the commodities signal the coming economic recovery. But I was intrigued by this Bloomberg report that China may have been strategically piling up a lot of commodities at very cheap price as a result of the collapse of the commodities across the board.

If that is the case, or assuming majority of these commodity imports are just for hoarding purpose, is the world economic recovery just a mirage? An interesting question worth more research.

Is inflation the solution?

Interview of William Poole and Brandeis’ Catherine Mann on why a 6% inflation, as advocated by some economists, will do more harm than good.

Adding to the discussion, I think moving to a higher inflation ‘target’ may also destroy the Fed’s hard-won reputation against inflation in Volcker era.

Monetizing debt looks seductive, but I hope the Fed will not go there.