Debt and inflation

Government and politicians have a tendency to use inflation to get out of their debt problem. Call it “debt monetization”. Here is a great chart from Casey’s Chart.

“The costs of things as measured by the consumer price index have risen twentyfold since the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. This act empowered the central bank to create and control a new currency for the United States, the Federal Reserve Note. Over this same period, the federal deficit soared from $2 billion to over $11 trillion. Coincidence? We think not.

After President Nixon cut the dollar’s ties to gold, funding the whims of government was no longer burdened by the need for higher taxes. Now any gaps in the budget can be filled by simply printing more dollars. And as you can see, the politicians didn’t hesitate to meet the challenge. Price levels and federal debt have risen hand-in-hand ever since.

The hidden tax of inflation has been stealing people’s buying power for nearly a century, but the opportunity to profit from it only comes about once every generation…”

US and global higher education boom

Following my previous post on China’s higher education boom/bubble, here I share with you another interesting research by Harvard labor economist Richard Freeman on how the global boom of higher education, especially in developing countries, has impacted on the US.

Exhibit 1 (all graphs are taken from Freeman’s NBER working paper) shows country’s share of global college enrollment.

In 2006, the US accounts for 12% of total college enrollment globally. But watch how China and India, the two most populous countries, how their college enrollments have soared over the years. China’s college enrollments rose from 1.7 million in 1980 to 23.4 million in 2006, or 16.5% of the world total.

A lot of college graduates from developing countries, seeking better opportunities, came to the United States. The chart below shows you the major source countries of international students in the US.

In the 2006-07 period, among 580K international students in the US, 2/3 are from Asia; 85% from developing countries: with India supplying the most, nearly 15%; China 12%; South Korea 10%. And nearly half (45%) of international students came to the US to pursue graduate degrees.

A lot of international students went to science & engineering (S&E) field. In 2005, 50.9% of PhD degrees in S&E were granted to foreign-born international students. If we just look at engineering, the number was at startling 69% (I believe the number is about the same in economics).

Focus on China: The number of students who came to the US to study and eventually got their PhD degrees in natural sciences has been rising sharply, especially after 1990s. (see graph below; the following graphs were taken from another NBER research by Bound, Turner & Walsh)

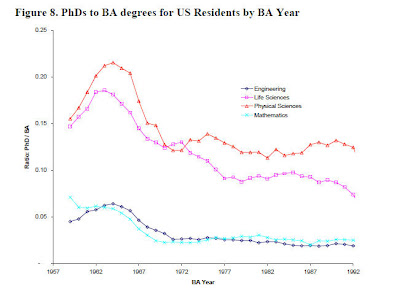

Meanwhile fewer and fewer US-born college graduates went to pursue PhD degrees. This is especially true in life sciences and physical sciences. I am not quite sure how this happened: it could be due to the education problem in US high school system; it could also be higher pay in other sectors, such as financials and investment banking.

But I suspect the surge of foreign PhDs in the US was largely a supply story. Why? The graph below looks at the correlation between the number of Bachelor degree holders and the PhD degrees granted in the US to foreign students. As you can see, there is an obviously strong positive correlation between the two.

Also, we have witnessed a cross-board surge of international students, almost in every field, not only in the science and engineering field.

Now we come to the policy delibrations.

With more and more PhD degrees granted to international students, foreign-born researchers and academics are sure to play a more and more important role in US higher education and research in coming years. A policy question naturally rises as to how to retain these foreign researchers. And what changes in US immigration policy should be in place to acheive the goal?

Marc Faber links inflation to pregnancy

A very interesting interview (with a lot of humor) of Dr. Marc Faber on the prospect of hyperinflation in the US.

He links inflation to pregnancy, “a little bit pregnant is as good as 100% pregnant”. A hilarious analogy! But he did raise a very intriguing question —why do economists unanimously think deflation is worse than inflation?

Watch part of the interview here on YouTube:

The sharp rising yield curve

The yield curve (the yield difference between 10-y and 2-y treasuries) has been rising sharply, to 2.75%, the highest level since Aug. 13, 2003.

Normally, rising yield curve signals economic recovery is well ahead. But the recent surge reflects probably much more of the market’s concern over government budget deficits and its ability to finance it. Either the government reins in spending, or the market will demand a higher interest rate as reflected in the rising yields of long-term government bonds.

Of course, government can always print money. So the alternative way of interpreting the current surge in the yield curve could be that the market is very nervous about higher inflation in the future so investors will demand the same real return on government bonds (nominal interest rate minus inflation).

(click to enlarge; source: calculatedrisk)

Also, with rising yield of 10-y treasury, the Fed’s effort in stimulating housing market through purchasing mortgage-backed securities will become less effective as the 30-year mortgage rates are closely tied to 10y treasury yields.

Regulation consensus

One such consensus is we need a regulator to look after the risks our financial system is taking as a whole. And what we need is not MORE regulation, but SMART regulation.

Watch this piece from David Wessel at Wall Street Journal: