Krugman: China’s Dollar Trap

Paul Krugman writes on NYT this morning:

China’s Dollar Trap

Back in the early stages of the financial crisis, wags joked that our trade with China had turned out to be fair and balanced after all: They sold us poison toys and tainted seafood; we sold them fraudulent securities.

But these days, both sides of that deal are breaking down. On one side, the world’s appetite for Chinese goods has fallen off sharply. China’s exports have plunged in recent months and are now down 26 percent from a year ago. On the other side, the Chinese are evidently getting anxious about those securities.

But China still seems to have unrealistic expectations. And that’s a problem for all of us.

The big news last week was a speech by Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of China’s central bank, calling for a new “super-sovereign reserve currency.”

The paranoid wing of the Republican Party promptly warned of a dastardly plot to make America give up the dollar. But Mr. Zhou’s speech was actually an admission of weakness. In effect, he was saying that China had driven itself into a dollar trap, and that it can neither get itself out nor change the policies that put it in that trap in the first place.

Some background: In the early years of this decade, China began running large trade surpluses and also began attracting substantial inflows of foreign capital. If China had had a floating exchange rate — like, say, Canada — this would have led to a rise in the value of its currency, which, in turn, would have slowed the growth of China’s exports.

But China chose instead to keep the value of the yuan in terms of the dollar more or less fixed. To do this, it had to buy up dollars as they came flooding in. As the years went by, those trade surpluses just kept growing — and so did China’s hoard of foreign assets.

Now the joke about fraudulent securities was actually unfair. Aside from a late, ill-considered plunge into equities (at the very top of the market), the Chinese mainly accumulated very safe assets, with U.S. Treasury bills”; T-bills, for short — making up a large part of the total. But while T-bills are as safe from default as anything on the planet, they yield a very low rate of return.

Was there a deep strategy behind this vast accumulation of low-yielding assets? Probably not. China acquired its $2 trillion stash — turning the People’s Republic into the T-bills Republic — the same way Britain acquired its empire: in a fit of absence of mind.

And just the other day, it seems, China’s leaders woke up and realized that they had a problem.

The low yield doesn’t seem to bother them much, even now. But they are, apparently, worried about the fact that around 70 percent of those assets are dollar-denominated, so any future fall in the dollar would mean a big capital loss for China. Hence Mr. Zhou’s proposal to move to a new reserve currency along the lines of the S.D.R.’s, or special drawing rights, in which the International Monetary Fund keeps its accounts.

But there’s both less and more here than meets the eye. S.D.R.’s aren’t real money. They’re accounting units whose value is set by a basket of dollars, euros, Japanese yen and British pounds. And there’s nothing to keep China from diversifying its reserves away from the dollar, indeed from holding a reserve basket matching the composition of the S.D.R.’s — nothing, that is, except for the fact that China now owns so many dollars that it can’t sell them off without driving the dollar down and triggering the very capital loss its leaders fear.

So what Mr. Zhou’s proposal actually amounts to is a plea that someone rescue China from the consequences of its own investment mistakes. That’s not going to happen.

And the call for some magical solution to the problem of China’s excess of dollars suggests something else: that China’s leaders haven’t come to grips with the fact that the rules of the game have changed in a fundamental way.

Two years ago, we lived in a world in which China could save much more than it invested and dispose of the excess savings in America. That world is gone.

Yet the day after his new-reserve-currency speech, Mr. Zhou gave another speech in which he seemed to assert that China’s extremely high savings rate is immutable, a result of Confucianism, which values “anti-extravagance.” Meanwhile, “it is not the right time” for the United States to save more. In other words, let’s go on as we were.

That’s also not going to happen.

The bottom line is that China hasn’t yet faced up to the wrenching changes that will be needed to deal with this global crisis. The same could, of course, be said of the Japanese, the Europeans — and us.

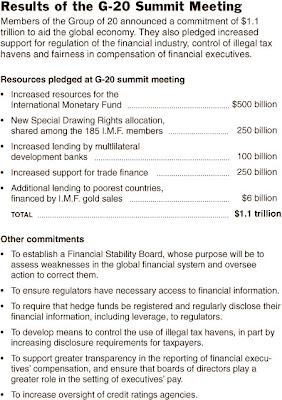

And that failure to face up to new realities is the main reason that, despite some glimmers of good news — the G-20 summit accomplished more than I thought it would — this crisis probably still has years to run.

A game of bookkeeping

Under PPIP, the new Geithner's plan, the troubled banks have every incentive to use government TARP money, to buy up its own or each other's toxic assets and make their balance sheets look instantly better.

The mechanism was explained in my previous video post here.

Now it looks like banks are considering doing just that (source: FT):

US banks that have received government aid, including Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase, are considering buying toxic assets to be sold by rivals under the Treasury’s $1,000bn (£680bn) plan to revive the financial system.

The plans proved controversial, with critics charging that the government’s public-private partnership – which provide generous loans to investors – are intended to help banks sell, rather than acquire, troubled securities and loans.

Spencer Bachus, the top Republican on the House financial services committee, vowed after being told of the plans by the FT to introduce legislation to stop financial institutions “gaming the system to reap taxpayer-subsidised windfalls”.

Mr Bachus added it would mark “a new level of absurdity” if financial institutions were “colluding to swap assets at inflated prices using taxpayers’ dollars.”

Participating in the plan as a buyer could be complicated for Citi, which has suffered billions of dollars in writedowns on mortgage-backed assets and is about to cede a 36 per cent stake to the government.

Citi declined to comment. People close to the company said it was considering whether to take part in the plan as a seller, buyer or manager of the assets, but no decision had yet been taken.

Officials want banks to sell risky assets in order to cleanse their balance sheets and attract new investments from private investors, limiting the need for the further government funds.

Many experts think it is essential to take these assets from leveraged institutions such as banks that are responsible for the lion’s share of lending, into the hands of unleveraged financial institutions such as traditional asset managers, where they will have much less impact on the flow of credit to the economy.

Banks have three options if they want to buy toxic assets: apply to become one of four or five fund managers that will purchase troubled securities; bid for packages of bad loans; or buy into funds set up by others. The government plan does not allow banks to buy their own assets, but there is no ban on the purchase of securities and loans sold by others.

“It’s an open programme designed to get markets going,” a Treasury official said. But he added: “It is between a bank and their supervisor whether they are healthy enough to acquire assets,” raising the possibility regulators may prevent weak banks from becoming buyers.

Wall Street executives argue that banks’ asset purchases would help achieve the second main goal of the plan: to establish prices and kick-start the market for illiquid assets.

But public opinion may not tolerate the idea of banks selling each other their bad assets. Critics say that would leave the same amount of toxic assets in the system as before, but with the government now liable for most of the losses through its provision of non-recourse loans.

Administration officials reject the criticism because banking is part of a financial system, in which the owners of bank equity – such as pension funds – are the same entitites that will be investing in toxic assets anyway. Seen this way, the plan simply helps to rearrange the location of these assets in the system in a way that is more transparent and acceptable to markets.

Goldman and Morgan Stanley have large fund management units and have pledged to increase investments in distressed assets.

This week, John Mack, Morgan Stanley’s chief executive, told staff the bank was considering how to become “one of the firms that can buy these assets and package them where your clients will have access to them”.

Goldman and JPMorgan did not comment, but bankers said they were considering buying toxic assets.