Stiglitz: What to do with toxic assets?

I am less convinced that letting big banks fail won’t have ripple effects. Stiglitz seems to have more of social justice in mind than global financial stability.

TALF

Yes, I am suffering a fatigue remembering these acronyms. But this one lends to hedge funds? Is the Fed losing mind?

Barro: Odds of depression

Robert Barro at Harvard applies his analysis on crashes and depressions to the current recession (source: WSJ).

full text:

What Are the Odds of a Depression?

International evidence suggests there is a 20% chance our stock-market crash will lead to much worse.

Central questions these days are how severe will the U.S. economic downturn be and how long will it last?

The most serious concern is that the downturn will become something worse than the largest recession of the post-World War II period — 1982, when real per capita GDP fell by 3% and the unemployment rate peaked at nearly 11%. Could we even experience a depression (defined as a decline in per-person GDP or consumption by 10% or more)?

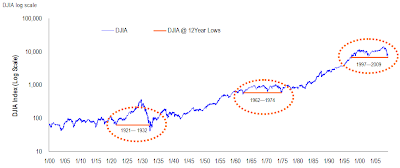

The U.S. macroeconomy has been so tame for so long that it’s impossible to get an accurate reading about depression odds just from the U.S. data. My approach uses long-term data for many countries and takes into account the historical linkages between depressions and stock-market crashes. (The research is described in “Stock-Market Crashes and Depressions,” a working paper Jose Ursua and I wrote for the National Bureau of Economic Research last month.)

The bottom line is that there is ample reason to worry about slipping into a depression. There is a roughly one-in-five chance that U.S. GDP and consumption will fall by 10% or more, something not seen since the early 1930s.

Our research classifies just two such U.S. events since 1870: the Great Depression from 1929 to 1933, with a macroeconomic decline by 25%, and the post-World War I years from 1917 to 1921, with a fall by 16%. We also assembled long-term data on GDP, consumption and stock-market returns for 33 other countries, sometimes going back as far as 1870. Our conjecture was that depressions would be closely connected to stock-market crashes (at least in the sense that a crash would signal a substantially increased chance of a depression).

This idea seems to conflict with the oft-repeated 1966 quip from Paul Samuelson that “The stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.” The line is clever, but it unfairly denigrates the predictive power of stock markets. In fact, knowing that a stock-market crash has occurred sharply raises the odds of depression. And, in reverse, knowing that there is no stock-market crash makes a depression less likely.

Our data reveal 251 stock-market crashes (defined as cumulative real returns of -25% or less) and 97 depressions. In 71 cases, the timing of a market crash matched up to a depression. For example, the U.S. had a stock-market crash of 55% between 1929-31 and a macroeconomic decline of 25% for 1929-33. Likewise, Finland had a stock-market crash of 47% for 1989-91 and a macroeconomic fall of 13% for 1989-93. We found that 30 cases where there were both crashes and depressions were also associated with wars. In fact, World War II is the worst macroeconomic event of the period, with strong U.S. wartime economic growth as an outlier.

In the post-World War II period, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries were strikingly tranquil up to 2008. The worst macroeconomic event in that period came in Finland in the early 1990s. Sweden also faced a financial crisis in the early 1990s, though it reacted quickly and is now being touted as a possible guide for leading the U.S. out of its current economic crisis.

Outside of the OECD, there have been many linked stock-market crashes and depressions since World War II — including the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, Mexico’s financial crisis in the mid-1990s, the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, and Argentina’s financial turbulence that lasted until 2002.

Looking at all of the events from our 34-country history, we find that there is a 28% probability that a “minor depression” (macroeconomic decline of 10% or more) will occur when there is a stock-market crash. There is a 9% chance that a “major depression” (a fall of 25% or more) will occur when there is a stock-market crash. In reverse, the chance that a minor depression will also feature a stock-market crash is 73%. And major depressions are almost sure to have stock-market crashes (our data show the probability is 92%).

In applying our results to the current environment, we should consider that the U.S. and most other countries are not involved in a major war (the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts are not comparable to World War I or World War II). Thus, we get better information about today’s prospects by consulting the history of nonwar events — for which our sample contains 209 stock-market crashes and 59 depressions, with 41 matched by timing. In this context, the probability of a minor depression, contingent on seeing a stock-market crash, is 20%, and the corresponding chance of a major depression is only 2%. However, it is still the case that depressions are very likely to feature stock-market crashes — 69% for minor depressions and 83% for major ones.

In the end, we learned two things. Periods without stock-market crashes are very safe, in the sense that depressions are extremely unlikely. However, periods experiencing stock-market crashes, such as 2008-09 in the U.S., represent a serious threat. The odds are roughly one-in-five that the current recession will snowball into the macroeconomic decline of 10% or more that is the hallmark of a depression.

The bright side of a 20% depression probability is the 80% chance of avoiding a depression. The U.S. had stock-market crashes in 2000-02 (by 42%) and 1973-74 (49%) and, in each case, experienced only mild recessions. Hence, if we are lucky, the current downturn will also be moderate, though likely worse than the other U.S. post-World War II recessions, including 1982.

In this relatively favorable scenario, we may follow the path recently sketched by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, with the economy recovering by 2010. On the other hand, the 59 nonwar depressions in our sample have an average duration of nearly four years, which, if we have one here, means that it is likely recovery would not be substantial until 2012.

Given our situation, it is right that radical government policies should be considered if they promise to lower the probability and likely size of a depression. However, many governmental actions — including several pursued by Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression — can make things worse.

I wish I could be confident that the array of U.S. policies already in place and those likely forthcoming will be helpful. But I think it more likely that the economy will eventually recover despite these policies, rather than because of them.

Mr. Barro is a professor of economics at Harvard and a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

Fed throws free money to hedge funds

Credit market is stuck, but is this the only way to get credit flow again? Old saying is, "Don't mess with markets!" —Government interventions make matter worse, creating distorted incentives (source: WSJ)

If you missed the first hedge-fund boom, now may be the time to put up your shingle. Looking at the terms of the Federal Reserve's new Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, investors using it should be able to generate hefty returns with little risk.

The TALF effectively turns the Fed into a generous prime brokerage. The central bank lends money for up to three years to investment firms to buy bonds backed by assets like auto or credit-card loans.

The Fed needs to lure investors back into the market for these asset-backed securities, or ABS, where new issuance has almost disappeared This has led to a contraction in lending to consumers, deepening the recession. In the fourth quarter of 2008, there wasn't any issuance of U.S. credit-card ABS, compared with $23 billion a year before, according to Dealogic.

Buyers have disappeared partly because they can no longer borrow the big sums once used to juice returns on ABS purchases.

The TALF ladles out that leverage, and it may well work in kick-starting the moribund market. For instance, investors can borrow $92 million to buy $100 million of bonds backed with prime auto loans. An investment firm would have levered its equity over 12 times, which could provide annual returns of over 20% on prime-auto ABS assuming no credit impairments.

What's more, the Fed, unlike a bank, won't demand the investor post collateral if the ABS market value falls over the three-year life of the loan.

What could go wrong? There is the risk of political outcry if investors reap massive gains. From a macroeconomic perspective, the TALF could distort the consumer deleveraging necessary for a lasting economic recovery.

Specific to the TALF itself, much depends on getting the pricing right. Hedge funds may want sweet returns, but issuers are going to want to issue at the lowest-possible interest rate. And since plenty issuers can borrow cheaply elsewhere right now, some can hold out and keep loans on their own books.

Lenders also may balk at the fact they can only issue triple-A-rated securities to TALF-funded buyers, meaning they have to retain lower-rated, riskier slices of the bond. That is good because lenders are likely to be more careful when making the loan it will then package up. But it could also hamper their appetite to issue large amounts of securitized product.

Perhaps the biggest risk is that TALF sucks liquidity away from other important segments of the debt markets, like longer-term corporate bonds. The Fed could get round this by broadening the TALF to include more types of assets. But that sucks it ever further into supporting credit markets.

The best outcome is that the TALF acts as a spark to rekindle the broader securitization market. But if credit markets remain sickly, the Fed faces the uncomfortable prospect of being "prime broker" to a huge investor base for years to come.

Sachs: Contingent Nationalization

A strategy of contingent nationalisation

By Jeffrey Sachs

One of the vexing problems of the US banking crisis is the difficulty of valuing the toxic assets on the banks’ balance sheets. The government is proposing to remove these assets in return for taxpayer equity in the banks, but at what terms of exchange? It seems that if the government pays too much it bails out the banks, while if it pays too little it de-capitalises them. There is way, however, to be both fair and efficient, by settling the taxpayers’ ownership at a later date, after the toxic assets have been monetised.

Consider a bank balance sheet with 100 in assets at face value, 90 in liabilities, and 10 in shareholder equity. For simplicity, suppose that the 90 in liabilities are in government-insured deposits. The assets are worth less than face value. Suppose that 80 of the assets are actually worth face value, while 20 are at a deep discount. If the true value of the 20 is 15, the true shareholder value is 5, while if the true value is only 5, the bank is insolvent, with zero true shareholder value and a government net liability of 5 to honour the deposit guarantee (once the bad assets are realised).

The problem is that the market value of the assets is not known now, because the credit squeeze has temporarily eliminated the liquidity in the markets of the toxic assets. There is an added problem. If the government pays fair value for the 20 of toxic assets, it willy-nilly forces a severe write down on the balance sheets even if it pays fair price. This in turn can lead to a further squeeze of lending. If the toxic assets are indeed worth 15, and these are swapped for 15 of government bonds, the recognised bank capital falls to 5, and capital adequacy standards would induce a further retrenchment of loans.

The bank can be recapitalised at fair value to taxpayers and without inducing a squeeze on bank capital and lending. The government can swap 20 in government bonds for the 20 in toxic assets plus contingent warrants on bank capital, the value of which depends on the eventual sale price of the toxic assets. The government would then dispose of the 20 in toxic assets at a market price over the course of the next year or two and exercise its contingent warrants at that time.

Warrants are securities that entitle the holder to buy shares of common stock at a specific price. Contingent warrants would entitle the holder, in this case the US government, to buy shares of common stock at a price contingent on the eventual sale price of the toxic assets.

The cleaned bank now has true market capital of 10, equal to 100 in good assets minus 90 in deposit liabilities. The 10 in equity would then be shared between the original shareholders and the taxpayers, with the division to be determined by the eventual sale price of the toxic assets. If the 20 in toxic assets end up selling at their face value, the taxpayers end up with zero ownership of the bank. If the toxic assets end up selling for less than 10, the bank ends up wholly owned by the taxpayers, because the bank is in fact insolvent at the time of the swap.

If the toxic assets end up selling for over 10 and less than 20, the taxpayers get an equity stake equal to 20 minus the eventual sale price. A sale price of 12 (of the 20 face value) leaves the taxpayers with 8 in stock ownership (20 minus 12) and the original shareholders with the remaining 2 (10 minus 8). The taxpayers are thereby fully compensated as long as the bank is solvent, and is left to cover the deposit liability in the event that the bank is insolvent. The shareholders also get the true value of their claims.

In this process, there are no taxpayer bailouts, and there is also no squeeze on bank capital resulting from the exchange of toxic assets at less than face value. In practice, the conversion of taxpayer warrants into bank equity would proceed step by step. Suppose that the taxpayers already own 2 and the shareholders own 8 as a result of partial liquidation of the toxic assets. Now, at a later date, additional sales of the toxic assets cause a further realized loss of 1. The bank would then issue further equity at that date equal to 1 (at the contemporaneous market value), further diluting the existing shareholder claims by 1 and raising the taxpayer stake to 3.

During the period of liquidating the toxic assets, the government would exercise a kind of receivership over the banks, preventing the stripping of remaining assets through bonuses, balance sheet transactions, or “Hail-Mary” lending (in which shareholders of zombie banks gamble recklessly because they have nothing to lose and possibly something to gain). In practice, this could be exercised in the form of a “golden share” which gives the government the right of refusal over major bank decisions, including executive compensation. Once the warrants are exercised, the government would sell its ownership stake to private investors.

The TARP has been stymied to this point over the valuation conundrum, stuck between paying an unduly high price for the toxic assets, and thereby bailing out the shareholders, and paying a low price, and thereby expropriating them while inducing a further credit squeeze. A “contingent warrant,” as recommended here, can combine bank recapitalisation with a fair value divided between the taxpayers and original bank shareholders.

Those 2x, 3x ETFs

Jason Zweig of WSJ warns the leveraged ETFs are not exactly as advertised:

Alcohol ads urge us to “drink responsibly.” Cigarette packs are emblazoned with the surgeon general’s warnings about cancer. And the firms that sell leveraged exchange-traded funds keep begging individual investors not to buy the things because they are meant only for short-term trading and can have erratic long-term returns.

Nonetheless, roughly 13,000 people are killed in alcohol-related crashes each year, over 33 million Americans smoke at least once a day — and more than $2 billion has poured into leveraged ETFs so far this year, much of it from financial advisers and retail investors who hang on too long.

ETFs are funds that trade during the day like stocks. A leveraged ETF seeks to use futures and other derivatives to multiply the daily return of a market index. Some, called “ultra,” “2X” or “3X bull,” attempt to double or triple the market’s return each day. Others try to double or triple the opposite of an index’s return; on a day when the market goes down, these “ultra-short,” “inverse 2X” or “3X bear” funds should go up two or three times as much.

On Thursday, the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index dropped 1.6%. ProShares UltraShort S&P500, which tries to deliver twice the inverse of the index’s daily return, went up 3.2% — right on target.

So why bother with a boring index fund when you could double or triple your money by using a leveraged ETF? And why helplessly watch your stocks wither away when an inverse leveraged fund could let you mint money in a falling market?

There are 106 such funds with $46 billion in assets, much of it “hot money” that flies right back out. On Wednesday, trading volume for Direxion Financial Bear 3X totaled 23.1 million shares on only two million shares outstanding — implying an average holding period of less than 34 minutes.

Leveraged ETFs are perfectly suited to such itchy-fingered traders, who can obsessively adjust their holdings to maintain a targeted level of exposure.

But even some “financial advisers,” who run ordinary investors’ money, hang onto leveraged ETFs the way a sharpshooter clings to a favorite rifle. And if you don’t understand how these funds work, you could take a bullet yourself. Their returns are predictable relative to the index only if you own them for one day or less. Over longer periods, say a week or more, these funds can wander wildly away from the underlying index.

When a market is trending in the same direction, a leveraged ETF can race ahead as it adjusts its leverage to its rising assets, jacking up its exposure to the market’s next move. Last Nov. 4 through Nov. 20, the Russell 1000 index of large stocks kept falling until it lost 25.6%. In response, Direxion Large Cap Bear 3X, an inverse fund, went up even more than its triple target; it rose 109.2%, four times as much as the Russell went down.

What happens when a market doesn’t take a straight path? Let’s say you were bearish on China and invested $10,000 in ProShares UltraShort FTSE/Xinhua China 25 on Oct. 9, 2008. Each day the Chinese market went down, this double-reverse fund went up twice as much. It also fell twice as much on any day when China rose.

These swings make it hard for a leveraged fund to match its targeted return in the long run; each loss requires a bigger gain just to get back to break-even. As the Chinese market heaved up and down over the next nine tumultuous trading days, $10,000 invested in Chinese stocks would have dropped to less than $9,200, a cumulative loss of 8%. Did the ultra-short fund deliver twice the opposite, or a 16% gain? No: According to data from Morningstar, it shriveled to $7,838, a 21.6% loss. So much for longer-term hedging.

Still, many financial advisers believe these funds are a good long-term hedge against falling markets. At a recent conference, roughly 50 financial advisers besieged Matthew Hougan, editor of IndexUniverse.com, a financial Web site, asking him to explain how leveraged ETFs work. Some “are starting to understand,” says Mr. Hougan, “but there is still a huge contingent out there who don’t.”

Like an amen corner, the leveraged ETF firms all say they keep trying to scare off long-term investors. The funds “are not a buy-and-hold vehicle,” warns Michael Sapir, chairman of ProShare Advisors. “These products are designed for trading use, not to be hedging tools,” insists Carl Resnick, vice president at Rydex Investments. Holding a leveraged ETF for longer than a day, says Andy O’Rourke, marketing chief at Direxion Funds, is “like using a toaster to cook a turkey.”

The bottom line: Leveraged ETFs are for day traders. You can’t manage long-term risk with a short-term tool — especially not with one that can blow up in your face.

Bank nationalization has already begun

According Martin Wolf, it’s become a semantic issue. The nationalization is already under way. (source: FT)

Lindsey Graham, the Republican senator, Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, and James Baker, Ronald Reagan’s second Treasury secretary, are in favour. Ben Bernanke, current Fed chairman, and an administration of liberal Democrats are against. What is dividing them? “Nationalisation” is the answer.

In 1978, Alfred Kahn, an adviser on inflation to President Jimmy Carter, used the word “depression”. So angry was the president that Mr Kahn started to call it “banana” instead. But the recession Mr Kahn foretold happened all the same. The same may well happen with nationalisation. Indeed, it already has: how else is one to describe the actions of the federal government in relation to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, AIG and increasingly Citigroup? Is nationalisation not already the big financial banana?

Much of the debate is semantic. But underneath it are at least two big issues. Who bears losses? How does one best restructure banks?

Banks are us. Often the debate is conducted as if they can be punished at no cost to ordinary people. But if they have made losses, someone has to bear them. In effect, the decision has been to make taxpayers bear losses that should fall on creditors. Some argue that shareholders should be rescued, too. But, rightly, this has not happened: share prices have indeed collapsed. That is what shareholders are for.

Yet the overwhelming bulk of banking assets are financed through borrowing, not equity. Thus the decision to keep creditors whole has huge implications. If we accept Mr Bernanke’s definition of “nationalisation” as a decision to “wipe out private shareholders”, we can call this activity “socialisation”.

What are its pros and cons?

The biggest cons are two. First, loss-socialisation lowers the funding costs of mega-banks, thereby selectively subsidising their balance sheets. This, in turn, exacerbates the “too big to fail” problem. Second, it leaves shareholders with an option on the upside and, at current market values, next to no risk on the downside. That will motivate “going for broke”. So loss-socialisation increases the need to control management. The four biggest US commercial banks – JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America and Wells Fargo – possess 64 per cent of the assets of US commercial banks (see chart). If creditors of these businesses cannot suffer significant losses, this is not much of a market economy.

The “pro” of partial socialisation is that it eliminates the risk of another panic among creditors or spillovers on to investors in the liabilities of banks, such as insurance and pension funds. Since bank bonds are a quarter of US investment-grade corporate bonds, the risk of panic is real. In the aftermath of the Lehman debacle, the decision appears to be that the only alternative to disorderly bankruptcy is none at all. This is frightening.

The second big issue is how to restructure banks. One point is clear: once one has decided to rescue creditors, recapitalisation can no longer come from the debt-into-equity swaps normal in bankruptcies.

This leaves one with government capital or private capital. In practice, both possibilities are at least partially blocked in the US: the former by political anger; the latter by a wide range of uncertainties – over the valuation of bad assets, future treatment of shareholders and the likely path of the economy. This makes the “zombie bank” alternative, condemned by Mr Baker in the FT on March 2, a likely outcome. Alas, such undercapitalised banking zombies also find it hard to recognise losses or expand their lending.

The US Treasury’s response is its “stress-testing” exercise. All 19 banks with assets of more than $100bn are included. They are asked to estimate losses under two scenarios, the worse of which assumes, quite optimistically, that the biggest fall in gross domestic product will be a 4 per cent year-on-year decline in the second and third quarters of 2009 (see chart). Supervisors will decide whether additional capital is needed. Institutions needing more capital will issue a convertible preferred security to the Treasury in a sufficient amount and will have up to six months to raise private capital. If they fail, convertible securities will be turned into equity on an “as-needed basis”.

This, then, is loss-socialisation in action – it guarantees a public buffer to protect creditors. This could end up giving the government a controlling shareholding in some institutions: Citigroup, for example. But, say the quibblers, this is not nationalisation.

What then are the pros and cons of this approach, compared with taking institutions over outright? Douglas Elliott of the Brookings Institution analyses this question in an intriguing paper. Part of the answer, he suggests, is that it is unclear whether banks are insolvent. If Nouriel Roubini of the Stern School in New York were to be right (as he has been hitherto), they are. If not, then they are not (see chart). Professor Roubini has suggested, for this reason, that it would be best to wait six months by when, in his view, the difficulty of distinguishing between solvent and insolvent institutions will have gone; they will all be seen to be grossly undercapitalised.

In those circumstances, the idea of “nationalisation” should be seen as a synonym for “restructuring”. Few believe banks would be best managed by the government indefinitely (though recent performance gives some pause). The advantage of nationalisation, then, is that it would allow restructuring of assets and liabilities into “good” and “bad” banks. The big disadvantages are inherent in organising the takeover and then the restructuring of such complex institutions.

If it is impossible to impose losses on creditors, the state could well own huge banks for a long time before it is able to return them to the market. The largest bank restructuring undertaken by the US, before last year, was that of Continental Illinois, seized in 1984. It was then the seventh largest bank and yet it took a decade. How long might the restructuring and sale of Citigroup take, with its huge global entanglements? What damage to its franchise and operations might be done in the process?

We are painfully learning that the world’s mega-banks are too complex to manage, too big to fail and too hard to restructure. Nobody would wish to start from here. But, as worries in the stock market show, banks must be fixed, in an orderly and systematic way. The stress tests should be tougher than now planned. Recapitalisation must then occur. Call it a banana if you want. But bank restructuring itself must begin.

![[Commentary]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ED-AJ110_Barro_DV_20090303165508.jpg)

![[Melting Plastic]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AV396_TALFHE_NS_20090303222515.gif)

![[How Managing Risk With ETFs Can Backfire]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-AV326_INVEST_D_20090227210414.jpg)