UK: the sick man once again?

Martin Wolf is worrying about UK's fiscal deterioration (source: FT):

Is the UK once again the economic sick man? Or is it, as Alistair Darling, chancellor of the exchequer, argued in his Budget speech on Wednesday, just one of a number of hard-hit high-income countries? The answers to these questions are: yes and yes. The explanation for this ambiguity is that the fiscal deterioration is extraordinary, but the economic collapse is not.

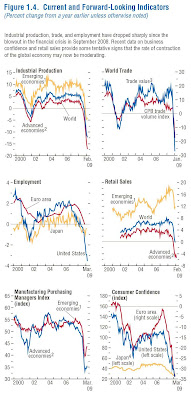

Let us start with the economy. According to the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook, the UK economy will contract by 4.1 per cent this year, followed by a further contraction of 0.4 per cent next year. This, it should be stressed, is far worse than the 3.5 per cent contraction in 2009 and 1.25 per cent expansion in 2010 forecast by the Treasury.

The IMF puts forward the following forecasts for other big economies: -3.8 per cent in 2009 and 0.0 in 2010 for all advanced countries; -2.8 per cent and 0.0 for the US; -4.2 per cent and -0.4 per cent for the eurozone; -5.6 per cent and -1.0 per cent for Germany; and -6.2 per cent and 0.5 per cent for Japan. Thus, the UK’s forecast performance is close to the mean for all advanced countries and better than for Germany and Japan.

The striking feature, indeed, is that the worst-hit economies are not those of profligate, high-spending countries, such as the UK and US, but of prudent, high-saving countries, such as Germany and Japan. People in the latter tend to see this as unfair, because it is undeserved. Well, life is unfair.

The serious answer is that the economic and financial health of sellers and creditors cannot be divorced from that of buyers and debtors. If customers are bankrupt, suppliers are likely to be in the same predicament. This is why Japan has suffered a collapse in manufacturing output comparable to that of the US during the Great Depression: a fall of 37 per cent since the start of 2008.

Now turn to the fiscal position. The IMF forecasts the UK general government deficit at 9.8 per cent of GDP in 2009 and 10.9 per cent next year. In the UK Budget, the Treasury forecasts the general government deficit at 12 per cent of GDP, or over, in 2009-10 and 2010-11. This suggests that the IMF forecasts are much too optimistic. Whether it is equally over-optimistic about other countries’ fiscal positions I do not know.

In any case, the IMF forecast deficit for the UK for next year is the highest in the Group of Seven leading high-income countries. Only Japan, on 9.8 per cent, and the US, on 9.7 per cent come close. Meanwhile, Germany’s deficit next year is forecast at “only” 6.1 per cent of GDP. Moreover, the 8.3 percentage point deterioration in the UK deficit between 2007 and 2010 is also the highest in the G7, with only Japan (a 7.3 percentage points deterioration) and the US (a 6.8 percentage points deterioration) coming close.

Not surprisingly, the UK is also forecast to have a relatively large deterioration in its net public debt, with a rise of 29 percentage points between 2007 and 2010 from 38 to 67 per cent of GDP. This time Japan, with a deterioration of 34 percentage points, is ahead, and the US, with 27 percentage points, just behind. But Germany’s rise is only 16 percentage points. Moreover, the UK’s net debt is forecast to continue to rise thereafter. It could well hit 100 per cent of GDP.

So why has the fiscal deterioration been so severe in the UK, when the economic deterioration has not been?

The obvious answer is that the sectors of the UK economy that have collapsed – housing and finance – are particularly revenue-intensive. As a result the ratio of current receipts to GDP is expected to shrink from 38.6 per cent in 2007-08 to 35.1 per cent in 2009-10 – a fall of 3.5 percentage points.

A deeper answer is that it is the countries where the debt-fuelled spending of the private sector was highest that have seen the largest swings in the balance between private income and spending. The shift in this balance in the UK’s private sector between 2007 and 2010 is forecast (implicitly) by the IMF at 9.6 per cent of GDP (from minus 0.2 per cent to plus 9.4 per cent). The swing in Germany, in contrast, is just 0.6 percentage points.

When the private sector shrinks its spending relative to incomes, either the current account or the fiscal balance must shift in equal and opposite directions. The current account deficit always changes relatively slowly. It is hard to change the economy’s structure quickly. So it has been the fiscal position that has deteriorated massively.

Thus, in the crisis-hit countries themselves, the consequence of the private sector cutback has been the fiscal deterioration. In the export-oriented countries, the result has been a massive contraction in exports and output. The huge fiscal deteriorations in the UK (and US) and the huge declines in manufactured output and exports in Germany and Japan are two sides of one coin.

So where does this leave us? The answer is that the next leg in the crisis, for both sides, will come when (or if) the huge fiscal deficits themselves become unsustainable. This is the great economic peril that lies ahead – and not just for the UK.

Will Americans turn into Europeans?

Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano at Harvard wonder about the question whether the crisis and the rising populism will turn Americans into Europeans.

The current financial crisis will reduce income and wealth inequality. The rich who heavily invested in financial and stock markets have lost much more than the less wealthy. The relatively poor “young” may face the sale of the century. Go and tell a young (and poor) just-married couple that the collapse of housing prices is a problem; mention to a young worker just beginning to accumulate retirement money that low stock prices are a problem!

Many will consider this reduction in inequality the silver lining of the crisis and a welcome development. This is especially the case because many people are acutely aware of the increase in income inequality that occurred in many (especially English-speaking) countries in the last three decades and perhaps tend to think of it as “unfair”. Those who became rich from complicated financial instruments and sophisticated investments in derivatives are now seen as undeserving of their wealth. The extraordinary bonuses of certain incompetent managers, especially those bailed out by the taxpayers, have certainly not helped gain them sympathy. Nevertheless, a frontal attack on the finance world is pure populism; finance serves a very productive purpose. One cannot mix criminals like Bernie Madoff with unlucky or even excessively leveraged, overly risk-taking, sometimes incompetent, and overpaid managers. Politicians should not throw fuel on any anti-finance or anti-Wall Street sentiments. There is enough anger against “unfairly” accumulated wealth; we do not need more.

The increase in income inequality of the last three decades in the US is not extraordinary if viewed from a very long-term perspective. The thirty years after the Second World War were the period of the “Great Compression” – a sharp reduction in income inequality (Piketty and Saez 2003). A few months ago, just before the crisis, we were back to roughly to the level of the 1920s, which was the norm in previous decades, not to mention the level of inequality and of social immobility of pre-capitalist societies. But the perception that this increase in inequality was unfair will greatly weigh on the way it will be handled and the political backlash it will create.

Our research (Alesina and Giuliano 2009) suggests that this is a situation in which voters will demand especially strong action to reduce inequality, even in a country like the US, where inequality is much more tolerated than in Europe. All over the world, the poor favour more redistribution than the rich, which is not surprising. But beyond that basic fact, the attitude towards what is the right amount of redistribution varies greatly and is affected by many more variables than just current income. In particular, when people perceive that the income ladder is the result of differences in hard work, effort, and creativity, even the relatively poor may accept large differences in income. This is partly because their sense of justice tells them that these are fair inequalities and partly because they feel that the income ladder can be climbed if it really depends only on effort and hard work. This is true both when comparing individuals within a country and comparing average attitudes across countries.

For instance, according to the World Values Survey, a large majority of Americans (around 60%) used to believe that the income ladder could be climbed and the poor could make it if they tried hard. Only a minority of Europeans (less than 40%) had the same view. That explains a lot of the difference in the generosity of the welfare state in the two places. Americans think that they live in a socially mobile society with less need for active public redistributive policies. Europeans, by and large, have the opposite feeling. Now Americans may feel that the social mobility that they cherished was not so large after all; investing in derivatives hardly has the same “feeling” in the popular sentiments as, say, working a late shift in a shop.

Therefore, this crisis may have changed American attitudes toward inequality a bit. If they perceive inequality as unfair they will demand more redistribution. The traditional aversion to taxation of Americans may give way to a “soak the rich” feeling. Higher taxes will be needed to handle the booming budget deficits. We would predict that the progressivity of the tax system will also increase, as the median voter will demand it. Politicians should resist such populist measures. Increasing the tax base rather than the brackets is the best way to increase taxes on the rich. A simplification of the byzantine tax code, where the wealthy can often hide income, is way overdue.

Will Americans turn into “inequality intolerant” Europeans? Probably not, but this crisis may imply a turning point towards more government intervention and towards redistribution.

References

Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano (2009) Preferences for redistribution, NBER Working Paper 14825.

Piketty, Thomas and Emmanuel Saez. 2003. “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1): 1–39.

Europe challenges world economic recovery

Report from today’s Journal:

Europe’s economy faces a deeper recession and a slower recovery than the U.S. or other parts of the world, making it the region that is most hurting prospects for an early end to the global economic slump.

The EU’s economy is set to contract 4% this year, even worse than the 2.8% drop projected for the U.S., according to new forecasts published Wednesday by the International Monetary Fund.

Those figures came as the U.K. released a budget that includes its biggest jump in the national debt since World War II. Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, shrank by 3.3% in the first quarter — a steep slide from a 2.1% contraction in the last quarter of 2008. Leading German economics institutes said Wednesday that the country’s economy is set to contract 6% this year, which would be its worst recorded performance since 1931.

European banks’ losses from the global financial crisis are now projected to overtake U.S. banks’ losses, according to IMF figures, which could hurt the banks’ ability to lend liberally to help the bloc out of its crisis. More than half of the losses on continental Europe are homemade, the IMF said, reflecting bad loans to European firms and households rather than toxic U.S. securities.

The worsening outlook for the 27-nation EU is a blow for many of the region’s governments, who have argued that the U.S. is the center of the global economic storm and that Europe’s problems are smaller. Because of that, plus fear of rising inflation and public debt, authorities in much of Europe have been slower than those in the U.S. or leading Asian economies to cut interest rates or adopt ambitious fiscal-stimulus measures.

“At some deep level the European banks and policy makers don’t get it: that they helped cause the crisis, that their slow response is part of the reason that the economy is bad, and that more is on the way,” says Simon Johnson, a former IMF chief economist.

Europe’s poor prospects are likely to rebound on the U.S., Asia and other regions, given that the EU’s $18.4 trillion economy makes up 30% of the world economy.

In a sign of such spillover, Peoria, Ill.-based equipment maker Caterpillar Inc. said its first-quarter sales to Europe fell 46% from a year ago, significantly more than its sales declines in the U.S., Asia or Latin America, as it announced a first-quarter loss on Tuesday.

Even European firms’ hopes are pinned on other regions where countries are spending more on stimulus plans. At Munich-based engineering firm HAWE Hydraulik SE, owner Karl Haeusgen is hoping that signs of life in the U.S. and China will lead to new export orders. In recent months, his orders have fallen as much as half from a year ago.

HAWE is holding on to its workers at idle German factories only because the government is helping to pay their salaries — a policy many European countries use to damp unemployment figures. “That we have a downturn is not surprising, but the intensity is unexpected and abnormal,” says Mr. Haeusgen.

In France, labor protests became more violent this week as workers stormed and ransacked a government building near Paris, after they failed in court to prevent their tire factory, owned by German auto-parts company Continental AG, from being shut down. German Trade Union Federation head Michael Sommer warned his country’s industrialists this week that such social unrest could spread to Germany if mass layoffs multiply.

On Tuesday, credit-rating agency Standard & Poor’s predicted that debt defaults among high-risk European companies would overtake defaults among low-rated U.S. companies.

Some business surveys and economic data suggest the pace of Europe’s contraction might be easing. But signs of a recovery in coming months appear weaker than in other regions, such as Asia and the U.S., where economists say more aggressive government efforts are starting to show some effect.

Tentative signs of relief in Asia include Chinese factory output and auto sales, which improved in March. Japan is also seeing some glimmers of hope, as exports in March nearly halved from a year earlier but rose from February, the first monthly gain since May last year.

Policy makers are partly to blame for the severity of the euro zone’s slowdown, say some analysts. “When you think of the broader monetary and fiscal policy mix, it’s clearly been more aggressive in the U.S.,” says David Mackie, economist at J.P. Morgan in London.

The European Central Bank cut its key interest rate to 1.25% from 4.25% in October, and is expected to trim the rate to 1% in May. That’s still well above comparable rates in the U.S. and U.K.

Governments in Europe also have been slower to use fiscal policy to support demand.

Fiscal stimulus measures over a three-year period of 2008-2010 are equivalent to 4.8% of last year’s gross domestic product in the U.S. and 4.4% in China, according to the IMF — but only 3.4% in Germany, 1.5% in the U.K., and 1.3% in France.

The weakening of Europe’s banking sector is potentially more damaging for the wider economy than woes at U.S. banks, because Europe’s financial system relies more on bank lending and less on securities markets. Although Europe’s banks have bigger balance sheets than U.S. lenders, so that their losses are smaller as a proportion of total assets, they will need more fresh money than the U.S. to repair their capital buffers, the IMF said.

An IMF report published Tuesday said that write-downs at Western European banks outside the U.K. will total $1.109 trillion for 2007-2010, topping the U.S. total of $1.049 trillion. Banks in the euro zone have so far written down only 17% of their losses, compared with roughly 50% at U.S. banks, the IMF said. U.K. banks have written down about a third of their $310 billion in expected losses, the report said.

Restrictive lending by banks trying to repair their capital ratios is holding back European businesses. At French racing-bicycle maker Look Cycle International SA, sales are suffering because the bicycle stores and distributors it deals with in markets including France and Italy can’t get enough financing, says Look Chief Executive Thierry Fournier. “Dealers and distributors have problems with their banks, so everybody is more cautious about placing orders or holding stocks,” he says.

Fixing the banking system is particularly tricky in the EU, where 16 of the 27 countries share the euro currency and a central bank, but where banking regulation mostly remains the preserve of the national governments.

“In Continental Europe, there is basically no prospect of any coordinated policy action to identify the weaknesses in the banking system,” says Nicolas Veron, a research fellow at Brussels think tank Bruegel.

Europe’s economy also faces a greater risk of further deterioration than other regions because of the deep economic and financial crisis in the formerly communist East. Austria-based banks, for example, have some $278 billion in exposure to those countries, equivalent to over 70% of Austria’s gross domestic product.

The IMF expects Continental European banks’ losses on emerging-market assets to reach $172 billion by 2010, more than four times the emerging-market losses it expects for U.K., U.S. or Asian banks.

McCulley: bottoming vs. recovery

Interview of PIMCO’s Paul McCulley: housing price is bottoming out but huge inventory will take time to clear. He also commented on PPIP and Janet Yellen’s recent speech on Minsky Meltdown.

China’s Electric Car Market: The battle is on

China has the strongest incentives to develop the cutting-edge electric cars. Why? Because China has the world’s largest population and the fastest growing economy; the rising middle class love the freedom of owning and driving a car; meanwhile, China is one of the most polluted countries in the world and the pressure to improve its environment is the greatest. How to find a middle ground that satisfies consumer demand while relieving the pollution pressure? The answer is electric cars.

China’s recent decision to adopt and subsidize electric cars will fundamentally change the auto industry in the world.

The investment of Chinese government in electric cars (the battery technology for example) will spur global competition in energy-saving technology. At the same time, the size of China’s domestic auto market also helps automakers to lower the cost of new technology really fast. One of the obstacles to develop electric cars in the US is automakers worry about the market for electric cars will be too small to make a profit. In other words, there is a lack of economy of scale. But with China in the game, automakers shall have no more worries. The US automakers have the option to sell the most-advanced electric cars to China. This in turn will force the US to rethink about its strategic position in global automobile industry. More policy changes in Washington will come naturally out of pressure from the other side of the Pacific.

Why can’t US government provide such incentives to automakers first? Because the oil-addicted Big-3 have their strong lobbying power in Washington. Thomas Friedman, the famed New York Times columnist, out of desperation, had once suggested the US had one day of dictatorship so government can force everybody to switch to cleaner technology. Well now, there is no need for that. China’s authoritarian government just did a favor to the US and to the world.

Competition is good: it works in economics and business; it also works in politics.

Read more about the coming battle of electric car market in China (source: WSJ):

SHANGHAI — Chinese auto makers are unveiling a slew of battery-powered cars and other energy-efficient vehicles at this week’s auto show here that could make them more globally competitive and eventually help address the air pollution that chokes many Chinese cities.

Alternative-fuel cars were some of the hottest items on display at the Shanghai auto show from homegrown companies like Geely Automobile Holdings Ltd., Brilliance Jinbei Automobile Co. and Chery Automobile Co.

Some of the new and updated models, such as a battery-powered version of Geely’s Panda hatchback, may hit the market as early as October, and in some cases they might carry price tags low enough for farmers and other rural residents with limited financial means.

![[China BYD Electric Car photo]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-DN222_cauto0_D_20090421094229.jpg)

The aggressive plans illustrate China’s growing commitment to electrified vehicles and its strategy to support auto makers developing various types of electric cars and components with research subsidies. The government sees environmental upsides and a chance for its car makers to gain ground on foreign rivals, since electric vehicles are simpler to engineer than gasoline-engine ones.

Electric vehicles are “definitely affordable and environmentally friendly technology, and we think there’s a huge potential market in China for them,” Li Shufu, Geely’s chairman, said in an interview Monday.

Making electric vehicles affordable will be critical for them to have an impact on the environment, as vehicle ownership continues to rise quickly. The hundreds of thousands of new cars being added every year to roads in China could further damage already shaky air quality if they are oil-based vehicles.

The battery-powered cars that Chinese companies are showing are intended to be much less expensive than those planned by big foreign companies. Great Wall Motor Co., based in northern China’s Hebei province, on Monday unveiled its planned GWKulla all-electric car, which will likely be one of China’s cheapest battery-powered cars when it hits showrooms as early as next year. Its expected price tag is between 60,000 yuan and 70,000 yuan, or about $8,780 to $10,250. The GWKulla, a short, curvy compact, runs on lithium-ion batteries and can go 160 kilometers (99 miles) when fully charged, the company says.

Chery showed a tiny battery car, the Riichi M1, that boasts similar technology and performance, and is likely to be priced under 100,000 yuan. Geely’s Panda, which Geely executive Frank Zhao said the company plans to launch in China as early as October, will be similarly priced.

Those prices are much lower than that of General Motors Corp.’s Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid, which is expected to sell for $40,000 when it goes on sales in the U.S. in late 2010. GM plans to launch the Volt in China in 2011.

Chinese auto makers also showed other types of “new energy” vehicles, including regular gasoline-electric hybrids to compete with Toyota Motor Corp.’s Prius hybrid. Among the most notable: a gas-electric hybrid Shanghai Automotive Industry Corp. plans to launch by the end of next year.

China’s technologies for electric vehicles, especially batteries, are still lagging behind in some important ways. And while many of the cars being shown this week in Shanghai are touted as “cutting edge” by their producers, it remains unclear how well they will perform — and how Chinese consumers will react to such “new energy” cars.

In early testing, reviewers said a plug-in electric hybrid sedan from China’s BYD Co. launched late last year had some kinks. The car, called the F3DM, was launched at least a year ahead of a similar car planned by Toyota. But the gasoline engine in the BYD rattled and could be noisy when it kicked in, the reviewers said. The steering wheel also tends to get stiff when making turns because of the car’s increased weight from the batteries. BYD has said it is aware of these issues and is working resolve them.

“From what we have seen so far, [Chinese electric vehicle] technology is not that advanced” in terms of things like battery life, driving range and recharging, said Nick Reilly, head of GM Asia-Pacific operations, on Monday. “However, they have pretty good cost, and we know the Chinese government and these Chinese companies are investing a lot of money in battery technology, so I think it would be foolish of us to ignore them and believe that we are that far ahead.”

Some regulatory and market characteristics make China one of the most promising markets to experiment with electric cars. The government’s regulations and policies for things like building electric-car charging stations can be changed more easily here than in places like the U.S. Most Chinese buyers also are purchasing cars for the first time and have not developed particular preferences.

Still, “the challenge here is consumers are extremely value-oriented,” said Raymond Bierzynski, head of GM Asia-Pacific engineering operations. “They’re very much interested in the payback, so we have to be [make sure] value is there.” One key move GM is counting on to make the Volt more affordable in China is government incentives, whether they are cash incentives for customers or subsidies for fleet purchases by government agencies.

Another notable battery car, though its producer decided to skip the Shanghai show, is a super-low-cost, two-seat mini electric car that Chinese parts producer Wonder Auto Technology Inc. and Korean golf cart maker CT&T Co. are expected to begin producing jointly this summer. Though equipped with decidedly low-tech lead-acid batteries and having a top speed of only 60-to-65 kilometers an hour, the car can go 100 kilometers when fully charged, according to the two companies.

The car’s biggest appeal is its rock-bottom price of less than 40,000 yuan. Wonder Auto’s chairman and CEO, Qingjie Zhao, believes the Chinese-Korean joint venture in Jinzhou (Liaoning province) could boost sales of the car to 50,000 vehicles a year within three years.

“A plug-in hybrid selling for 150,000 yuan is a pipe dream for farmers. It would take five to 10 years before they become truly affordable for everyday folk,” Mr. Zhao said. “But low-cost commuter EVs like ours is already a reality, within the reach of thrifty farmers.”

O’Neill calls China "red hot"

Interview of Goldman Sachs chief economist Jim O’Neill on global economic outlook. He expects positive GDP growth in the US in 3Q, and he says many economists will have to revise their forecast on China’s growth, to a much higher level.

Copper as leading economic indicator, Part 2

Weekly chart of Copper May 2009 future price:

(click to enlarge; source: WSJ Online)

To follow up my previous post on Copper as leading economic indicator, here I show you some recent data (courtesy of BCA research) that seem to confirm the story.

The first graph looks at the correlation between copper price and global industrial production (IP). Several interesting observations out of the graph: 1) Copper price is more volatile than IP in recent years (since 2000) as well as late 80s. 2) The predicative power of copper started to show up in early 90s; before that, copper was more like a coincident indicator and sometimes even lagging indicator. This, I suspect, may have something to do with China’s integration into the world economy since 90s. 3) Recently, the copper price started to turn the corner. Does this mean the world economy may soon turn the corner, too? Read on…

A counter argument could be: China has been strategically buying copper at very low price (see graph below), but the buying itself does not mean China is having an economic recovery. To link copper price to economic rebound, we need to see the real “green shoots” in the Chinese economy.

So where are the green shoots? Chinese government has been increasing money supply and loan growth sharply (see graph below) to counter the deflationary pressure and stimulate the economy. And the effect was quite effective. At least, China does not have the problem of banking not lending.

In export sector, there are also signs that Chinese economy have turned the corner (see the graph below).

Personally, to make the copper story more convincing, I’d like to see the data of copper inventory flow — then we can decipher how much copper purchase was pure strategic buying from China and how much was due to actual recovery.

To summarize, I am cautiously optimistic about China’s outlook.